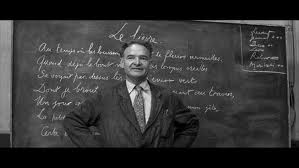

Towards the end of Midnight in Paris, the main character Gil (Owen Wilson) suggests a movie idea to a young man accompanying Salvador Dali. The man (played by Adrien de Van) was Luis Buñuel, the Spanish filmmaker and poet who caused a outrage with his first two films, Un Chien Andalou (1928) and L’Age d’Or (1930), both collaborations with the surrealist painter, Salvador Dali. The latter film was banned for nearly 50 years before it had its premier in the U.S. in 1979.

(By the way, the movie that the Owen Wilson character was suggesting was Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel.)

Buñuel and his compatriot Dali were at the forefront of surrealism and, while their artistic vision was not embraced by everyone, both men practiced their art well into old age. And while the difficulty of surrealism coupled with Buñuel’s savage attacks on the bourgeoisie and on religion might have distanced himself from much of the mainstream audience, he was quickly seen as a seminal figure in film and one of its greatest directors. His films won or were nominated for major awards throughout the world.

Both his anti-religion and the anti-bourgeoisie attitudes are in full display in Buñuel’s 1972 film The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. And of course, the entire film is surreal. ..and quiet funny.

..and quiet funny.

While plot has never been the most stringent part of Buñuel’s films, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie focuses on three couples and a series of quirky events and odder dreams that continually prevent them from dining together. There is also a Catholic bishop who asks to moonlight as one couple’s gardener. (It is typical of Buñuel that the bishop performs the most brutal action in the film.)

There are gentle stabs at the military, the police, and the upper-middle-classes, but overall the film is relatively light–at times even farcical. Etiquette is important to the three couples–and propriety–despite the fact that the men are drug smugglers and their life style is founded on drug money. They talk about the proper way to drink a martini and bemoan the fact that the lower classes do not know how–this they see as evidence of the downfall of society. (They use their chauffeur as a test case.)

Throughout the film, dreams occur within dreams within dreams…and at times we forget that some of the situations the characters find themselves in dissolve upon waking. And the dreams themselves get increasingly brutal. There are various ghosts and visits to the underworld and dreamlike violence.

And all these well-to-do people want to do is eat a meal together–and they can’t…a rare event for people who are used to getting everything they want. Life–as surreal as it can be–gets in the way.

By the way…

The original title for the movie was Down with Lenin, or The Virgin in the Manger (A bas Lénine, ou la Vierge à l’écurie) and was changed to The Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Adding the word Discreet was an afterthought.