Joan Didion.

illustration 2013 jpbohannon

based on portrait by Lisa Congdon for Reconstructionists project

Joan Didion.

illustration 2013 jpbohannon

based on portrait by Lisa Congdon for Reconstructionists project

“Build a good name. Keep your name clean. Don’t make compromises, don’t worry about making a bunch of money or being successful — be concerned with doing good work and make the right choices and protect your work. And if you build a good name, eventually, that name will be its own currency.”

Patti Smith (remembering advice she got from William S. Burroughs)

The philosopher, political theorist and writer, Hannah Arendt has received a thoughtful and deserving biopic from director Margarethe von Trotta, in her eponymous film, Hannah Arendt. The film’s intelligence reflects the life of the mind that Arendt lived–and an honest and hard intelligence at that. Concentrating on the period when Arendt covered the Adolph Eichmann trials for New Yorker magazine–and the fury that it unleashed– it shows Arendt resolute in her thinking, uncolored by prejudice or sympathies.

Her coverage of the Eichmann trial ended with these words, this pronouncement:

Just as you [Eichmann] supported and carried out a policy of not wanting to share the earth with the Jewish people and the people of a number of other nations—as though you and your superiors had any right to determine who should and who should not inhabit the world—we find that no one, that is, no member of the human race, can be expected to want to share the earth with you. This is the reason, and the only reason, you must hang.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Arendt’s biography is well know. Born into a secular Jewish family, she studied under Martin Heidegger with whom she reportedly had a long affair. Her dissertation was on Love and Saint Augustine, but after its completion she was forbidden to teach in German universities because of being Jewish. She left Germany for France, but while there she was sent to the Grus detention camp, from which she escaped after only a few weeks. In 1941, Arendt, her husband Heinrich Blücher, and her mother escaped to the United States.

From there she embarked on an academic career that saw her teaching at many of the U.S.’s most prestigious universities (she was the first female lecturer at Princeton University) and publishing some of the most influential works on political theory of the time.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

But the film, concerns a small time period in her life–but one for which many people still hold a grudge. The film begins darkly with the Mosada snatching Eichmann off a dark road in Argentina. Back in New York City, Arendt (Barbara Sukowa) and the American novelist, Mary McCarthy (Janet McTeer) are sipping wine and gossipping about the infidelities of McCarthy’s suitors. Even genius can be mundane–perhaps a subtle reference to Arendt’s conclusions from the trial. When news of Eichmann’s arrest–and trial in Israel–is announced, Arendt writes to William Shawn (Nicholas Woodeson) at the New Yorker, asking if she might cover the trial for the magazine. Shawn is excited; his assistant, Francis Wells (Megan Gay,) less so.

But the film, concerns a small time period in her life–but one for which many people still hold a grudge. The film begins darkly with the Mosada snatching Eichmann off a dark road in Argentina. Back in New York City, Arendt (Barbara Sukowa) and the American novelist, Mary McCarthy (Janet McTeer) are sipping wine and gossipping about the infidelities of McCarthy’s suitors. Even genius can be mundane–perhaps a subtle reference to Arendt’s conclusions from the trial. When news of Eichmann’s arrest–and trial in Israel–is announced, Arendt writes to William Shawn (Nicholas Woodeson) at the New Yorker, asking if she might cover the trial for the magazine. Shawn is excited; his assistant, Francis Wells (Megan Gay,) less so.

Of course, the trial–and Arendt’s commission to follow it–is fascinating and controversial and we listen in on Arendt and her husband and their circle of friends as they debate and argue and opine. Aside from Mary McCarthy and the head of the German department at the New School where Arendt is teaching, the guests at Arendt’s apartment are all friends from Europe, German-Jews who have escaped the Shoah/Holocaust. Listening to their different conversations is fascinating and electrifying. This is a movie about “thinking.”

In Israel, Arendt meets with old friends, friends who remember her argumentative spirit, and stays with the Zionist, Kurt Blumenfeld. From the outset, one sees that Arendt is not thinking along the same lines as the masses following the trial.

At the trial, there is a telling moment, when Arendt watches Eichmann in his glass cage sniffling, rubbing his nose and dealing with a cold. It is then, a least in the film, that she comes to understand that this monster is not a MONSTER. She sees him as simply a mediocre human being who did not think. It is from here that she coins the idea of the “banality of evil.”

Upon returning home–with files and files of the trial’s transcripts–her article for the New Yorker is slow in coming. Her husband has a stroke, and the enormity of what she has to say needs to be perfect.

When it is finally published, the angry reaction is more than great. The critic Irving Howe called it a “civil war” among New York intellectuals. (Just last week, the word “shitstorm” was added to the German dictionary, the Duden, partly due to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s use of the word to describe the public outcry she faced over the Eurozone’s finacial crisis. It is an apt term for what occurred upon publication of Arendt’s coverage.)

It is this extraordinary anger towards Arendt–and her staunch defense–that makes up the final moments of the film. In the closing moments, Arendt speaks to a packed auditorium of students (and a few administrators). She has just been asked to resign, which she refuses to do. These are her closing words:

“This inability to think created the possibility for many ordinary men to commit evil deeds on a gigantic scale, the like of which had never been seen before. The manifestation of the wind of thought is not knowledge but the ability to tell right from wrong, beautiful from ugly. And I hope that thinking gives people the strength to prevent catastrophes in these rare moments when the chips are down.”

This is, more than anything else, a film about thinking.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

The extraordinary anger shown in the film is still felt by many today and, in fact, seems to have colored some of the reviews that I have read and heard. Some of these reviewers seem to be reviewing the life and work of Arendt and not the film of Margarethe von Trotta, for von Trotta’s film is a unique, masterpiece. It is more than a biography of a controversial thinker…it is a portrait of thought itself. Arendt attempts to define “evil”–certainly an apt exercise at the time. She defines it–to her friends, to her classes, to her colleagues, and to herself–and finds that it is not “radical” as she once had posited. It is merely ordinary. Goodness, she sees, is what has grandeur.

The film, Hannah Arendt, is well worth seeking out. It is thoughtful, provoking, controversial, and, at times, even funny. You can’t ask for much more for the price of a movie ticket. As always, here’s a trailer:

Adam Phillips begins his small book Darwin’s Worms with a story about the composer John Cage. Cage had attended a concert by a friend. In the program notes to the concert the friend had written that he hoped in some small way that his music helps to ease some of the suffering in our modern world. When Cage criticized this desire, the friend asked him if he didn’t think there was too much suffering in the world. “No,” replied Cage. “I think there is just the right amount.”

And so, Phillips writes, it is to remind us of and reconcile us to the fact that the amount of suffering in life is just the right amount that we turn to Darwin and Freud.

Darwin was very aware of the suffering in the natural world. Anticipating Freud on one level, he saw all organisms in a war for survival, thrust forward by an instinct to regenerate, adapting continually to a constantly changing environments. While the rest of his society were arguing, debating, proselytizing what it believed were the weightier implications of Darwin’s observations, Darwin studied the lowly earthworm, understanding its importance in the life of nature and, in turn, our own, (which he would argue is part of nature and not separate from). Flipping the usual symbolism on its head, removing the lowly worm from man’s symbolic last meal (“not where he eats, but where he is eaten”) and placing it at the continual meal that is life, Darwin points out that worms function in nature like plows, turning over soil and creating the soft and germinating loam that we take as the earth’s surface. As they struggle to survive (and “struggle” and “survival” are both key words in Darwin and Freud’s lexicon), worms leave behind shards of the past–that which they cannot digest–and form suitable soil for the plants that will provide for their future. Darwin states that:

“…it would be difficult to deny the probability that every particle of earth forming the bed from which the turf in old pasture land springs has passed through the intestines of worms.” That is a very large contribution to life on earth, powered simply by the worm’s instinctual drive to survive.

Later, Freud elaborated this drive, this instinct to survive and coupled it with its antithesis, the death instinct. At first, he termed them simply, the life instinct and the death instinct. Ultimately, he gave it the poetic designation of “Eros and Thanatos.” The life instinct is easy to understand. Man is driven to survive and to propagate. (“To be or not to be” becomes “to survive or not to be.”) The latter, however, the death instinct is a bit more difficult to get one’s head around. Freud believes that in the struggle to survive man also has a desire to cease that struggle–to stop the pain, if you will. However, the desire, says Freud, is also to be in control of that death. To make it part of one’s life story.

Later in the book, Phillips gives us passages from two separate biographies (“life stories”) of Freud. Both describe the same scene, Freud’s death (“death stories”). The scenes themselves are poignant, but what Phillips does with the passages is telling. In it, he shows Freud “controlling his death” the way that he thought all humans desired. In a way, it is a heroic portrait and an affirmation of Freud’s theories.

As Phillips concludes, in their work, both Freud and Darwin “ask us to believe in the permanence only of change and uncertainty… . to describe ourselves from nature’s point of view; but in the full knowledge that nature, by (their) definition, doesn’t have one.” In an work that analyzes mortality, death, and loss, Darwin’s Worms is a surprisingly upbeat and reassuring view of the world.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Freud famously said that there are no such things as coincidences. But today as I opened my computer to begin writing this post about Darwin and Freud, the homepage on my computer opened to this New York Times article revealing the discovery of the fossil of a nearly complete skeleton of what is the earliest primate known, changing scientists’ time-line for the appearance of primates on earth by 8 million years, and giving credence to the growing theory that primates emerged first in Asia rather than Africa.

Xijun Ni/Chinese Academy of Sciences An artist’s interpretation of a tiny primate that is thought to be the earliest known ancestor of nocturnal primates living today in Southeast Asia. from NYTimes 06/06/2013

How appropriate. Darwin would have been excited, for he saw great value in studying the simplest and earliest of life-forms, plankton, barnacles, and earthworms.

In the office of a colleague a while back I noticed a towering pile of books on the desk, as if he were re-arranging his book shelves or carting out old titles to a different location. But no, it was his “to read” pile, and it was impressive and imposing.

Philips, “Poetry and Psychoanalysis”

The crux of Phillips’ essays is the mutual relationship between literature and psychoanalysis…and psychoanalysts’ established reverence for creative writers. Literature, according to Freud, gave birth to psychoanalysis and psychoanalysis often gives resonance to literature.

And so go his essays.

He begins with the essay “Poetry and Psychoanalysis” and brings in the young poet Keats–a former medical student–who famously stated that science ruined poetry when Newton reduced the rainbow to a prism. Not so, Phillips says, for poetry (and you can read “creative writing” where Phillips says “poetry”) can do what the sciences cannot. Indeed, much of his argument is that the science of psychoanalysis is bringing understanding to the vision of poetry. Freud said, Phillips tells us, that the poets had long before discovered the unconscious, and that he only had devised a way to study it.

Phillips graciously gives way to “poetry” saying that the short history of psychoanalysis has been an attempt to study the unconscious that poetry reveals. And since both poetry and psychoanalysis–the “talking cure”–depend on language, and often, coded language, the two are intrinsically welded together.

And so he is off.

There are marvelous literary essays on Hamlet, Hart Crane, Martin Amis, A.E. Housman and Frederick Seidel, all informed by an accessible shading of psychoanalytic theory, as well as masterful psychoanalytic pieces on Narcissism, Jokes, Anorexia and Clutter, informed by a broad knowledge of literature/poetry. It is Phillips’ contention–his modus operandi, if you will–that the two disciplines can or should depend on each other for clarity.

The collection ends with the title piece, “Promises, Promises.” In it, Phillips examines the “promise” that both literature and psychoanalysis offer. He writes:

The collection ends with the title piece, “Promises, Promises.” In it, Phillips examines the “promise” that both literature and psychoanalysis offer. He writes:

“If we talk about promises now, as I think we should when we talk about psychoanalysis and literature, then we are talking about hopes and wishes, about what we are wanting from our relationship with these two objects in the cultural field.”

What does reading literature promise us? What does analysis promise us? Phillips contends that both promise us, to a degree, “the experience of a relationship in silence, the unusual experience of a relationship in which no one speaks.” Of course, ultimately, the analyst must speak. But it is in that silence that often we become “true to ourselves.”

Reading psychoanalytic theory can often be dry and dusty, but Phillips’ writing never is. Bringing in an encyclopedic knowledge of both creative literature and psychoanalytic literature (and, at times, arguing that there might not be a difference), Phillips imaginatively and wittily plumbs past and current trends, canonical and esoteric literatures, clinical practice and private correspondence to bring to light his vision of psychoanalysis and literature’s potential and promise.

A colleague of mine passed on a book that he liked very much. Dirty Snow by the prolific Belgian writer, George Simenon. I had read several of Simenon’s detective novels, gritty tales that featured the Parisian detective Maigret. The Maigret novels–I believe there are over fifty of them—seemed superior to most in that genre, filled with a certain ennui and jaded acceptance that went beyond the cynical aloofness of his American counterparts or the aloof cynicism of his more modern offspring. And to be honest, they were good reads.

Although I had read only the Maigret novels, I knew that Simenon wrote other sorts of novels. I had always heard them referred to as “philosophical” novels, though the French label them as “psychological” novels. And the French are closer to the truth, here.

And when my colleague passed on to me Dirty Snow, he did so with the caveat that it was “extremely grim” although oddly humanistic.

Dirty Snow is the story of Frank Friedmaier making his way through his occupied city. We never know who the occupiers are and where the city is. When he is imprisoned, his captors, his location, and his crime are never identified. All of this, gives the novel a certain Kafkaesque feeling. And although time moves forward throughout the seasons, there seems always to be piles of soiled, stained, and dirtied snow.

And yet it was Crime and Punishment that I thought of immediately. Frank–who may be the most amoral, sociopath I have come across in my reading, and I know Burgess’s Alex and Ellis’s Bateman–begins the novel looking to kill his first person. There is no reason for, no gain from this murder–it is, as he says, like losing his virginity: “Losing his virginity, his actual virginity, hadn’t meant very much to Frank. He had been in the right place. … And for Frank, who was nineteen, to kill his first man was another loss of virginity hardly any more disturbing than the first. And like the first, it wasn’t premeditated.” Like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, he needs little push to kill his victim. Yet, there the similarity ends. For Raskolnikov punishes himself, mentally, emotionally, spiritually and psychologically for the crime he committed. Frank feels nothing. And soon he kills again…an old woman in his childhood village who recognized him in the course of a burglary.

But the murders are not his greatest crime. That is reserved for the sweet and loving Sissy who lives across the hall from the brothel that Frank’s mother runs and where Frank lives. (Sissy mirrors very closely Raskolnikov’s Sophia in her love and faithfulness to Frank.) Frank’s relations with women are brutal at best–indeed all the women in the novel seem mistreated one way or another. He takes full advantage of his mother’s prostitutes, coldly, quickly and unemotionally, and this is the way he treats Sissy as well, deceiving her into a situation where she is nearly raped by his drinking associate.

One might say there is no reason for Frank’s viciousness, but that would be inaccurate. There is no “motive,” no “purpose” for his ferocity. But there is a reason, and Simenon attempts to suggest it subtly. Frank’s mother abandoned him to a wet-nurse so she could “ply her trade” and visited only occasional. He never knew his father, only the brutality of both life and the State. Two men are offered as father surrogates in the novel: one, a Maigret-like inspector who turns a blind eye to Frank’s mother’s occupation and who very well may be his biological father and Sissy’s father, Holst, who Frank is drawn to from the beginning, who sees Frank in the alleyway on his first kill, and who offers him forgiveness at the end.

But many men have similar upbringings and few turn out as nihilistic, amoral, and unfeeling as Frank. To his interrogator he says at the end: “I am not a fanatic, an agitator, or a patriot. I am a piece of shit.” There is nothing. Yet the flip side of that is that there is nothing the State offers either. They have not arrested him for the murders or the burglary. They have brought him in, they torture him merely for information. And here, in the claustrophobic room where he is questioned, one remembers a similar room–Room 101 in Orwell’s 1984. But Frank is no Winston Smith either; there is no romantic dream of something better, no fervid belief in the ultimate progress of what is right. There is only Frank, solipsistic and brutal Frank.

Simenon’s novel is fascinating. His hero is repellent. And I can’t stop thinking about neither it nor him… It’s sort of like wearing wet shoes, soaked through by dirty snow.

I am reading about nothing. Literally, about nothing. I am reading about the concept of nothingness, and it’s a pretty difficult thing to get one’s head around.

Philosophers, theologians, mathematicians, and physicists have been puzzling the concept for a very long time, and it is quite a hot button in philosophical and scientific circles today.

In the West the concept of nothing is relatively new.

In fact, it wasn’t until the mid-14th century that the idea of “zero” came to the West. And then, it came to us through accounting. Something had to stand between asset and debit.

The East, however, had long dealt with nothingness not only in their mathematics but in their spirituality as well. For after all, attaining “nirvana” was equal to attaining nothingness, to achieving “emptiness.”

The Hindu word for this nothingness was sunya, which became in Arabic sefir, which came to Europe in the Middle Ages and is the root of our word “zero” and “cipher.” And when it came to Europe, it came along with the rest of the Arabic numerals that we use today.

And yet what is nothing? There are many who say that no such thing exists.

The philosopher Henri Bergson tried to imagine nothingness. He simply kept subtracting all that he knew existed. However, when he reached the end he felt there was still something–his inner self which was doing all this subtracting. (An enlightened Buddhist would perhaps be able to extinguish that entity, but most of us cannot.) He concluded that imagining absolute nothingness is impossible.

Another philospher, Bede Rendell, saw that the failure in imagining nothingness is that after one had subtracted everything that was in the universe, one still had the space where those things once existed–a universe skin collapsed on itself.

The entire conversation is both intriguing and maddening, puzzling and wondrous. (Sort of like in Alice in Wonderland when the Red King concludes that since nobody passed the messenger on the road, then nobody should have arrived first.)

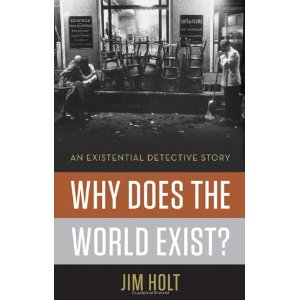

I am having this “conversation” with myself because of the book Why Does the World Exist?–An Existential Deterctive Story by Jim Holt. Holt’s book, which is somewhat addressed to the lay reader (I can only imagine what a technical book on this subject might be like), springs from the question “Why is there Something rather than Nothing?”

This question, I have learned, is one that has puzzled philosophers for aeons.

And when you get to the question of “something” and “nothing” you are led to the question of what “existed” in the universe before the “Big Bang” created the universe. The theologians have their answer. The scientists are not all that sure. But they have their theories.

And both try to define or dismiss “nothing.”

All of which makes for fascinating reading. Even the mathematical equations (which Holt has to explain to me or which I run to my resident philosopher/mathematician) are fascinating. For instance, his mathematical equation for absolute nothingness is

(X) ˜ (x=x)

and now seems to makes some sense to me. But it took a while for me to get to. (The equation means that X [the empty universe] is not where x = x [where something is something.]) He explains it much better and is much more entertaining.

I am no philosopher or mathematician. My sense of the void, of nothingness–aside from my own existential angst and probings seeemingly hardwired in my soul–comes from Satre, Camus and Beckett. And Holt brings these into the mix as well. (The cover of the book features a photograph of the Café de Flore, a favorite haunt of Sartre’s.) The book, in many ways, is almost a primer of thinkers, ancient and new, and a wonderful introduction to the confluence of metaphysics, philosophy, literature and science.

And what they ask is: Why is there something rather than nothing? Why is there a world? A universe?

These are pretty big questions to roll around with and Holt’s book makes it a entertaining and informative ride.

But to be truthful, I still don’t know the answer.

I went to see a band tonight down at a local pub, The Dark Horse, known more for soccer clubs and televised soccer games than for music. But some friends of mine are in this band and I had to see them.

I have played with two of the members before in an Irish band, but this new band, The Flashbacks, is just that …a flashback to several decades earlier. The band started out as a Beatles cover band, but then expanded with a lot of Steely Dan, Yardbirds, Stones, Kinks, before settling into CSNY, Beach Boys, the Dead, Eagles, etc. (They tout themselves as the second British Invasion, but they cover a fair amount of American bands as well.)

And the reason they can cover this music is that they are DAMN GOOD! The harmonies are precise–three-part most of the time–and the musicianship is impeccable. They are seasoned players who have, for the most part, known each other for a very long time and they play to each others’ strengths and build on it. The youngest member–Joe Manning–is just a pup compared to the others, (he wasn’t born when these guys first started playing together) but he is one of those wunderkinder who can play anything and play it with perfect beauty, wit and definition. If he had been alive forty-five years ago, they would have called him a god.

And so this got me to thinking….

There are an awful lot of very talented people out there. I could go see scores of really talented bands or individuals every night of the week in my city alone. Multiply that by every other city, burg, town. How many great musicians are there in Dublin? Edinburgh? Berlin? London? Madrid? Cairo? Innumerable.

I know very talented artists, amazing writers, magical poets, extraordinary designers who day in and day out work at their craft (or because of the ways of the world, work at their “day-job” and then work at their craft) and create wonderful pieces. I am sure you know similar people in your parts of the world. What separates these artists from those who’ve become household names?

Luck, certainly plays a role, but a very minimum one. Being at the right place at the right time, meeting someone who can truly help, etc. are all fortunate but are not the thing that separates the very good from the great. And mere technique is not sufficient–there are thousands of technically gifted people.

I believe it is focus, focus on one’s calling at the expense of all else.

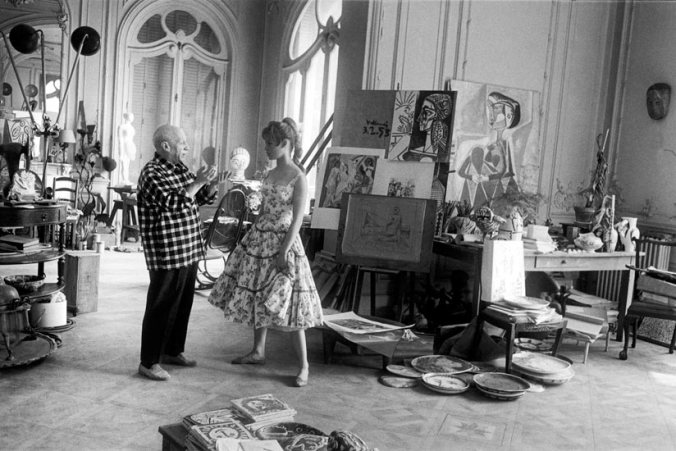

Picasso and Bardot. How great is that?

re-posted from http://weekendspast.com

I remember having a discussion with my father once. He was bemoaning the way that Picasso treated women, discarding them indiscriminately whenever it suited him. I argued that it was a symptom of his genius. (He challenged my assumption that Picasso was a genius.) Genius, I said, uses everything it comes across. There is nothing else that matters but his or her art, his or her genius–other people and other people’s emotions included.

The conversation came up again this week, when someone remarked on seeing the television movie Hemingway and Gellhorn on what an unlikeable cad Hemingway actually was. Again, it is all ego wrapped around his art…or maybe the opposite, all his art is wrapped around his ego.

The attitude can be summed up in the clichéd saying “It’s his (her) world, we’re just living in it.”

Who else has stepped on everyone to further their art–or in the furtherance of their art? We could cite both Shelley and Byron, who stepped on and used everyone in their belief in their own genius and the entitlements it should deserve.

But this is not only in the arts. Steve Jobs may have been a genius but he was hardly a likeable person. And Bobby Fischer, arguably the greatest chess player ever, became more than simply an egocentric genius. He became a misanthropic, hate monger.

Mozart–a man who could create entire operas in his head without touching an instrument–was certainly egocentric, almost to an infantile degree.

So what about all your acquaintances who are truly talented, gifted people? Is it that they are decent human beings whose company you enjoy, whose interest in you and others around them is obvious, that keeps them from reaching the pantheon of genius.

And would you have it any other way? I know I wouldn’t! I too much enjoy the people who are creating wonderful, beautiful things–like the middle-aged Flashbacks at The Dark Horse pub–and who are still wonderful human beings, interested in the world and the people around them.

The etymology of the word “amateur” comes from the word Latin word “amat” –to love. Whether one is paid or nor, celebrated or not, it is the love of doing, making, performing something that is good and beautiful that makes for a better world.

I’ll go see the Flashbacks, the next time they play!

I have been sick for the past five days. Sick enough that I have come home from work every night and gone straight to bed. Sick enough that I am existing on juice, tea, aspirin and kleenex. Sick enough.

This morning I said to someone “I don’t even want to be inside this body anymore.” Not really sure what that meant, but it got me thinking. Who was talking there? Who is this “I” that feels itself a guest inside this “body”? Of course, I couldn’t let it go from there.

I had to look for answers.

The questions are hardly new: ancient Greeks and the early Hindu yogis each grappled with the Mind-Body Problem. In the modern world, it was Descartes on one side and Spinoza on the other side of what became contrasting points of view. Descartes and the Dualists believed, in essence, that the mind and the body were separate entities. This seems to jibe with the Yeatsian view in yesterday’s post that something existed apart and before the body was made. Of course, as philosophers are wont to do, the Dualists have splintered into various groups as well.

Spinoza and the Monoists believe that the mind and the body are one. Our feeling that these two entities are distinct is simply the properties and emanations of the brain. With recent advances in neuroscience, brain-mapping, psychology, etc., it appears that the mononist position has been gaining strength. Yet it too has broken into several splinterings. The most basic is that between reductive and non-reductive. The reductive believe that ultimately all mentality, all mindfulness, will be able to be explained through a scientific understanding of our physicality. The non-reductive agree that all there is to the mind is the brain and its functions, but believe that its functions cannot be “reduced” to the parameters and terms of physical science.

So all of this is scary stuff. What does it mean if our “self” is really just a creation of the physical firings and synapses of our brain in conjunction with the countless other functions going off –or awry–in our body each moment. If our “self” is truly just a construct of our brain, then that construct can be manipulated. Don’t think so? Advertisers, politicians, behaviorists do! It is, after all, their job to make you do, buy, think, act in a way that you did not necessarily consider before. Their livelihoods are predicated on your “self” being manipulated.

I know that at the moment my own body is misfiring–sinuses are clogged, limbs are achy, head is pounding, throat is soar, lungs are tender. Yet who is “the self” that is getting fed-up at that body, fed-up at the slow pace of recovery. It would seem that I am dealing with dualism here. And yet, intellectually I side with the monoists.

I guess, my little old brain has simply been formed in a way that tends to have these thoughts while my body hits these speed-bumps. It’s all part of the package.

The Official Web Site of LeAnn Skeen

Grumpy younger old man casts jaded eye on whipper snappers

"Here is my secret. It is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.."- Antoine de Saint Exupéry

Of writing and reading

Photography from Northern Ontario

Musings on poetry, language, perception, numbers, food, and anything else that slips through the cracks.

philo poétique de G à L I B E R

Hand-stitched collage from conked-out stuff.

"Be yourself - everyone else is already taken."

Celebrate Silent Film

Indulge- Travel, Adventure, & New Experiences

Haiku, Poems, Book Reviews & Film Reviews

The blog for Year 13 English students at Cromwell College.

John Self's Shelves

writer, editor

In which a teacher and family guy is still learning ... and writing about it

A Community of Writers

visionary author

3d | fine art | design | life inspiration

Craft tips for writers