A good while back, I saw the film A Dangerous Method. I was enthralled. Depicting the budding relationship and subsequent falling out between Freud and Jung, and hanging it on the larger story of Sabina Spielrein, it introduced me to a history that I did not know.

Freud and Jung as played by Viggo Mortensen and Michael Fassbender in the film A Dangerous Method.

Like most people, I knew about Freud and Jung to varying degrees, and probably a little more than the average reader. An avocation of sorts, I had read much more of Freud than of Jung: I had read several volumes of his works, different collections of his letters and several biographies and was more conversant with Freud’s vocabulary than with Jung’s. (Though I once had read a fascinating collection of letters between Jung and Herman Hesse that I remember mostly because upon finishing it, I had a startling–and still remembered–dream featuring the floating head of an exotic woman repeating the Sanskrit term, kamakeli. I would love to find those letters now–or a psychoanalyst to help me through the dream.)

But what I hadn’t known about until the film A Dangerous Method (based on the book of the same name by John Kerr) was the existence–or the importance–of Sabina Spielrein. And so I began reading. First, I read the Kerr book on which the film was based. Then I read Jung–a relative hole in my reading. And this week I read a small book entitled Sex versus Survival: The Story of Sabina Spielrein–Her life, her ideas, her genius by John Launer. Launer is a senior staff member at the Tavistock Clinic–the preeminent institute in the U.K. for psychological training and a senior lecturer at the medical school of the University of London.

The stated purpose of his book is to give due to Spielrein, whom he believes should be ranked among the major figures in the history of psychoanalysis–and who is not because of injustice, malfeasance, and patriarchal insecurities, particularly at the hands of Freud and Jung. He divides his book into three sections: Spielrein’s biography, Spielrein’s work, and Spielrein’s influence on 21st-century evolutionary psychoanalysis.

Her Life

In 1904, Spielrein was brought to Switzerland–having been turned away from various clinics–to be treated for severe psychic disorders. There she was first treated by Eugen Bleuler, head of the clinic, and later by his protege, Carl Jung. In fact, Spielrein would be the first patient to be psychoanalyzed by Jung. She would also soon become his lover.

Sabina Spielrein

Within a year, Spielrein’s symptoms had abated so that she had entered medical school in Zurich–while still being treated by Jung and entagled romantically with him. Together, the two debated and discussed the psychoanalytic topics of the day–with Spielrein progressively formulating and stating her own views.

However, before long, Jung saw her as a liability. (He was married and a respected figure in the early days of psychoanalysis. And he had certainly crossed a line with a damaged patient’s understandable “transference.”) He wrote to his mentor–and idol–Freud about the situation, though not naming names. She at the same time wrote to Freud. Freud wrote to Jung and the two discussed her as if she were nothing more than a case study. And so we have the two giants of psychoanalysis trying to quell a female colleague (and former patient and former lover) and cover up what would have certainly have been a professional and personal scandal. This would go on for a long time–a power play mixed with antisemitism (was the Christian Jung attracted to her “otherness”?), patriarchy, chauvinism, and professional insecurity.

When Spielrein read her paper–“Destruction as the Cause of Coming into Being”– to the bearded Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, (she was only the second woman to belong to the Society and a mere 26 years old), she focused on the biological factors at play in the sexual life of humans. Freud adamantly wanted psychoanalysis to have no connection whatsoever with biology (although he started out as a talented neurologist) and dismissed this major–and prescient–part of her paper. And when she brought mythology in to support her argument, Freud saw traces of Jung, with whom by now he was becoming completely disenchanted.

The two wrote about her–crudely at times–and patronizingly discussed her views. And then they buried her: Jung–the editor of the Society’s journal–held her paper for a year before publishing it. Freud, in a snit about Jung, associated her too closely with him and gave her views barely a glance. When he did correspond with her, it was to analyze why she fell for Jung in the first place. As Launer writes, the two dealt with Spielrein by “pathologising the victim, and ignoring her ground-breaking ideas.” (p. 99)

And yet, her views influenced both men significantly. For Jung, she was instrumental in developing his theory of the anima and animus; for Freud, she brought the thanatos to his eros, the “death wish” to his “pleasure principle.”

Spielrein moved on, becoming a leading figure in child psychology. (She was Jean Piaget’s psychoanalysist.) When she returned to her native Russia, she introduced psychology and psychoanalysis to the Russian medical system. But history was moving too fast. First the communists closed down the psychology departments, then forbade psychoanalysis, then came down heavy on all the sciences. Her brothers– a physicist and a biologist– were sent to labor camps and never heard from again.

And then came the Nazis. In the summer of 1942, Nazi soldiers marched into the town of Rostov. They gathered the people and marched them to the Zmeyevsky gully–a mass grave at the edge of town where mass executions took place. Sabina Spielrein was among those killed.

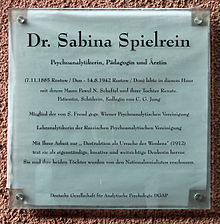

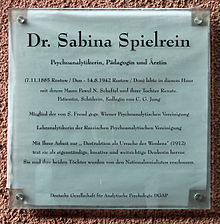

Plaque in front of the Berlin house where Sabina Spielrein once lived.

Her Work and Influence

Launer spends the second half of the book describing the text of her initial paper to the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. She began by equating the “invasion” of a sperm fertilizing an egg with the sex act itself and stated that in sex–both personal and genetic–something is loss (or killed) in the evolutionary drive to replicate itself. Launer then goes on to say, that despite her mistakes and misdirections, that she was greatly prescient and anticipated some of the major theories of 21st century biology and evolutionary psychology. Three of his final chapters take her three main positions and reword them as a modern evolutionary biologist would put them. Here is how he pairs them:

According to Speilrein’s first principle, ˆReproduction predominates over survival”

Speilrein wrote: “The individual must strongly hunger for this new creation in order to place its own destruction in its service.”

Modern Evolutionary Theory says: “The imperative of all living organisms is the replication of their genes by direct or indirect means in the face of individual extinction.”

According to Speilrein’s second principle, ˆSex is a form of invasion, leading to the destruction of genes from both partners to the reconstitution of new life.”

Speilrein described sex as a process of destruction and reconstruction at every level : “a union in which one forces its way into another.”

Modern Evolutionary Theory says: “As well as co-operation, sexual reproduction involves inherent conflict at every level between male and female genetic interests.“

According to Speilrein’s third principle, “Human feelings correspond with the biological facts of reproduction.”

Speilrein wrote: “It would be highly unlikely if the individual did not at least surmise, through corresponding feelings, these internal deconstructive-reconstructive events.”

Modern Evolutionary Theory says: “Our feelings correspond to the way we balance opportunities for genetic continuation against the risks of extinction.“

In her writings, Spielrein anticipated the “selfish gene” of Richard Dawkins; she anticipated a needed convergence of Darwin and Freud; and she brought biology onto the psychoanalyst’s couch. Perhaps, she was so far ahead of her time that her theories could not be proven, tested, or validated, but she was also stymied by forces more powerful than she.

The story of Sabina Spielrein is fascinating, a story of love and passion, of intelligence and perseverance, of betrayal and destruction. It is Launer’s contention that Spielrein’s name should be as familiar to us as the name of her two more famous male colleagues. The depth of her influence is still be discovered–her papers were not found until the 1970s–and it is certain that her contributions to psychology and evolutionary biology is still yet to be fully appreciated.

collection of seven essays, mostly first-published on the web-site TomDispatch, that focus on the reality and the dangers (and some of the absurdity) found in the patriarchy of modern civilization, dangers that include murder, violence, and rape, as well as condescension and subordination.

collection of seven essays, mostly first-published on the web-site TomDispatch, that focus on the reality and the dangers (and some of the absurdity) found in the patriarchy of modern civilization, dangers that include murder, violence, and rape, as well as condescension and subordination.