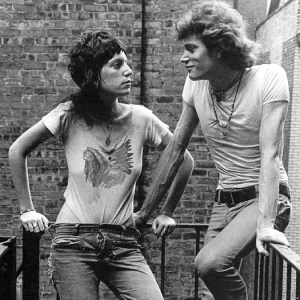

I discovered a documentary the other night called Black, White + Gray by James Crumb (2007). The blurb calls it a study of the relationship between the curator/collector Sam Wagstaff, the artist Robert Mapplethorpe, and the poet/singer Patti Smith. To be honest, however, it is really the story of Wagstaff, that touches greatly on his relationship with Mapplethorpe and to a much smaller degree with Smith, both for whom he was mentor and patron and friend. (In Mapplethorpe’s case lover and companion.) Consequently, it also deals with art, the business of art, the demimonde of gay life in the 1970s and 80s, and, of course, the scourge of AIDS.

Moving chronologically through Wagstaff’s life–and anchored by Patti Smith’s intelligent and honest and fond recollections–the film follows Wagstaff from his schooldays through his loathed time spent in advertising to his prominence in the art worlds of New York, Paris and London. Along the way, there are appearances on the Dick Cavett Show, press conferences, interviews with his friends and colleagues, and countless photographs, many taken by him or Mapplethorpe and many part of his historic collection.

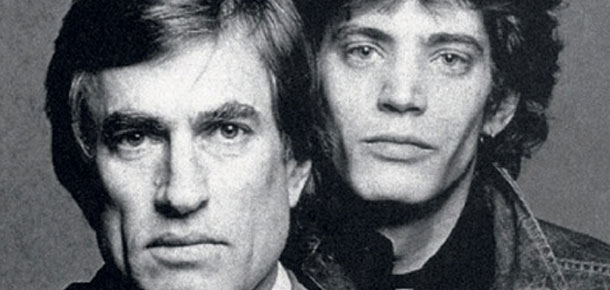

Wagstaff was strikingly handsome, aristocratic, and intelligent. (Dominick Dunne called him one of the most handsome men he ever saw.) He was also gay, but closeted himself for much of the oppressive fifties and early part of his life. Not until his meeting with Mapplethorpe did it seem he grew comfortable with his homosexuality. As a curator, he embraced and pushed forward those artists and art forms that were still on the fringe, Minimalism, Earth Works, Conceptual Art, and, most importantly, photography. Wagstaff believed that photography was an ignored art and deserved to be elevated to the pantheon of “Fine Arts.”

Indeed, it is because of Wagstaff that photography holds the status that it does today. His relentless collecting, the exorbitant sums he paid, the continual praise and comments in the press, single-handedly hauled photography onto the main stage.

A few years before he died, Wagstaff sold his private collection of photographs to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles for the then unheard-of price of $5-million. It was testimony to how far he had brought photography to the forefront.

The interviews within the film are honest and intelligent. Many deal with his collecting, with his curating, and with his “vision.” Many deal (some negatively, some positively) with his relationship with Mapplethorpe. Dominick Dunne, particularly, gets much air time, and talks about Wagstaff in two of the worlds that he lived in–the socialite world and the gay world. And all is brought together by the reminiscences of Smith.

“Compartmentalized” is a word that often came up, and it seemed that Wagstaff was very good in ordering his life into separate and distinct components. But in the end, it was the gay world that did him–and so many others–in. It is easy to forget that at one point, AIDS was a scourge that was decimating much of the art world. The film ends with Wagstaff’s death, and then with Mapplethorpe’s, and then with a list of the many artists who have died of AIDS complications since.

It is a sobering ending. But then the credits role and are intersperse with clips from the many interviewees and once again we are reminded of the life, of the visionary man who rose so high in the world of art–and brought others with him .

We know much about Mapplethorpe’s life, and Patti Smith’s, greatly due to her wonderful memoir, Just Kids. James Crumb’s film Black, White + Gray adds greatly to our knowledge of that time and that world and the people who populated it. It’s worth while finding and fascinating viewing.

By the way…

The title of the film, Black, White + Gray not only refers to the B&W Photography that Sam Wagstaff collected, cataloged, and often curated, or the shades of distinctions in the compartmentalized life that he constructed, but also to the momentous exhibited he staged at the Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum entitled “Black, White and Gray.” The exhibit, considered the first minimalist show, featured the work of Stella, Johns, Kelly, and Lichtenstein, among others. It was an extraordinary success, influencing fashion, Hollywood, advertising, and, of course, Truman Capote’s infamous Black and White Ball.

Andy Warhol at Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball without a mask.