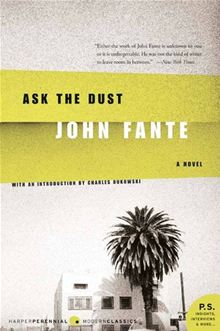

One of those weird coincidences: I began reading John Fante’s 1938 novel Ask the Dust late this past Tuesday night. I didn’t get far–maybe three chapters–but the story of a young writer who had moved to L.A. from Colorado had grabbed me. Wednesday morning, I wake up early, check my messages and e-mails and a few blogs that I read. One of them–francescannotwrite–has a picture of the Disney Concert Hall at the top and a quote from Fante’s novel: “Los Angeles, come to me as I have come to you.” (Besides the weird coincidence of the novel, I also had, just a few weeks back, put the Disney Concert Hall on my computer as its wallpaper.) The blog-post offered some examples of the novel’s humor, its brief passages of romance, and its overall feeling of gloom. And then it segued into some extraordinary pictures of Vietnam.

One of those weird coincidences: I began reading John Fante’s 1938 novel Ask the Dust late this past Tuesday night. I didn’t get far–maybe three chapters–but the story of a young writer who had moved to L.A. from Colorado had grabbed me. Wednesday morning, I wake up early, check my messages and e-mails and a few blogs that I read. One of them–francescannotwrite–has a picture of the Disney Concert Hall at the top and a quote from Fante’s novel: “Los Angeles, come to me as I have come to you.” (Besides the weird coincidence of the novel, I also had, just a few weeks back, put the Disney Concert Hall on my computer as its wallpaper.) The blog-post offered some examples of the novel’s humor, its brief passages of romance, and its overall feeling of gloom. And then it segued into some extraordinary pictures of Vietnam.

Anyway, so I finish the novel and it was a good read, although one that left a few questions unanswered. Episodes where the act of writing were described were particularly memorable, for it is hard to put down on paper the art of ART. Most times, it comes off as stagy and overly dramatic. But the scenes where Fante gives us two or three paragraphs of Arturo Bandini in a “creative” groove are fun to read. For instance, here is Bandini–having sold two short stories for a handsome price–sitting down to begin his novel:

Out of my desperation, it came, an idea, my first sound idea, the first in my entire life, full-bodied and clean and strong, line after line, page after page. … I tried it and it moved easily. But it was not thinking, not cogitation. It simply moved of its own accord, spurted out like blood. This was it. I had it a last. Here I go, leave me be, oh boy do I love it. … big fat words, little fat words, big thin words, whee whee whee.

But primarily, Ask the Dust is about obsession. The hero, Arturo Bandini, self-conscious of his Italian heritage and full of fluctuating self hate, falls madly in love with Camilla Lopez, a Mexican waitress at a cheap coffee shop. The entire novel, his writing, his day to day living, his memories of home become wrapped around her–or around deliberately hating her. For the relationship is a strange sado/masochistic thing that yo-yos between love and hate, between tenderness and violence, but that never vascillates in its obsession. Camilla too has her obsessions and it is the thrust of the novel that they are not the same as Arturo’s.

I have always been attracted to obsession. I remember reading the novel Damage by Josephine Hart in one sitting and being floored by the destructive obsession of its characters. (I can still remember cancelling a lunch appointment because of my emotional exhaustion. The film version, by the way, tries, but does not do it justice.)

But mainly I think of obsession as a good thing…as a passion that forms and defines you. And in this I turn to Yeats. My favorite Yeats’ poem is “The Song of Wandering Aengus.” The poem tells of discovering a great passion…and of following it throughout one’s life. There is a sadness in it, but one tinged with hope, colored with the concept that chasing the obsession is more important than actually attaining it.

The Song of Wandering Aengus

by W. B. Yeats

WENT out to the hazel wood,

WENT out to the hazel wood,- Because a fire was in my head,

- And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

- And hooked a berry to a thread;

- And when white moths were on the wing,

- And moth-like stars were flickering out,

- I dropped the berry in a stream

- And caught a little silver trout.

- When I had laid it on the floor

- I went to blow the fire a-flame,

- But something rustled on the floor,

- And some one called me by my name:

- It had become a glimmering girl

- With apple blossom in her hair

- Who called me by my name and ran

- And faded through the brightening air.

- Though I am old with wandering

- Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

- I will find out where she has gone,

- And kiss her lips and take her hands;

- And walk among long dappled grass,

- And pluck till time and times are done

- The silver apples of the moon,

- The golden apples of the sun.

And this is how, John Fante’s novel Ask the Dust leaves us. His Mexican girl has “faded through the brightening air” and, while he chases her through the foreboding desert, he is left to use her image, her memories, and his pain to create his next novel, to fashion his next work of art.

And so for something different on this snowy March day, here is a clip of the singer Christy Moore doing his version of Yeats’ poem. It never fails to bring a tear to my eye: