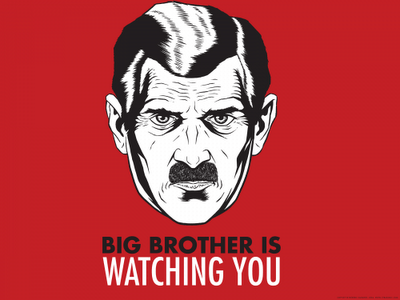

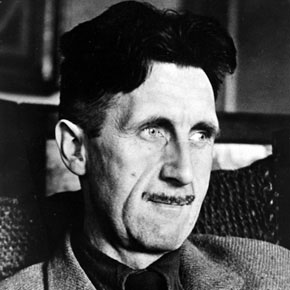

It is perhaps the most iconic novels of the 20th century. George Orwell’s 1984 is the dystopian novels of all dystopian novels. We all know the phrases “Big Brother,” “doublethink,” “thought-police”; their ominous overtones and insinuations are recognized even by those who have never read the book. The deadening conformity and mind-control that Orwell writes about are the fears often invoked by those who fear totalitarianism in any form–in governments or corporations.

Apple–now a mighty corporation in itself–famously advertised its new Macintosh computer by pitting itself against the corporate giants of the computer world in a magnificent television commercial that echoed the world of 1984–and Apple’s defiance to its conformity. (The ad was seen only once on television during the American Superbowl and then subsequently was shown in theaters.)

The novel is bleak and that bleakness is broken only briefly by a wonderful love affair and the main character’s misplaced hope. Indeed, my favorite image from the book is one that perfectly captures the grime, the incompetency, the substandard level of life, when Winston Smith, the protagonist, goes to unclog a sink in a neighbor’s apartment. As he looks at her, he notices the dust that has gathered in the lines of her face. I always remember that–a pretty powerful image.

Orwell wrote his novel in 1948 (that’s really the only significance of the novel’s title: it’s the year he wrote it reversed)

Orwell wrote his novel in 1948 (that’s really the only significance of the novel’s title: it’s the year he wrote it reversed) . But nearly a quarter century earlier, another British writer also wrote a powerful dystopic novel: Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

. But nearly a quarter century earlier, another British writer also wrote a powerful dystopic novel: Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

And where Orwell’s world is one in which a film of oil lies on the gin and ready-made cigarettes fall apart in your hand and where sex is frowned upon (because one should really only love Big Brother), Huxley’s novel is the opposite.

Huxley saw his dystopia as a world in which people are perfectly happy–indeed where they are conditioned to be happy. There is no disgruntlement–people have been conditioned to accept and love their station in life. (A station that has been pre-decided by the artificial generation process.) Promiscuity is greatly encouraged and sex is varied and plentiful. And if for some reason, one might feel a little blue, there is SOMA, a mood-enhancing drug that is given out in vast quantities to all the classes.

The society works efficiently and happily. Yet Huxley sees the snake in the garden–the lack of freedom to be wrong, to be sad, to disagree. Even to be alone. It is when a “savage” is brought back from a reservation in the southwestern part of the U.S. is the society and its beliefs challenged–but not for long.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

By the way, click here for a letter that Huxley wrote to Orwell upon first reading 1984. It is this very discussion of dystopia comprising great suffering or constant happiness:

Huxley to Orwell letter

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

I teach Brave New World as the first book of the new school year. I will have thirty very bright 18-year-old students enrolled in my class. I know that half of them read 1984 last year with the one teacher they had. The other half did not. (And 1984 is such a great companion piece to any discussion of Brave New World.) So I assigned it as “summer reading.” But only to half of them. I looked for another “dystopian” novel to give the class that had already read Orwell’s novel.

And so I assigned Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Now, I have never been a big fan of science-fiction. I have just never gotten into it. In fact, I have never seen a Star Wars movie!

I’ve read some of the standards–Bradbury, Welles, Asimov, and, if we are stretching, Vonnegut. But it’s something I just never made a connection with.

And Dick’s novel did nothing to change my mind!? Despite it being anointed a “classic” by so many and being the source for the beloved film, Blade Runner, it left me very flat.

Again we are dealing in a world different than our own–a post-apocalyptic earth where most of the able bodied people have emigrated to Mars. Nuclear fallout from World War Terminus has made much of Earth inhabitable. The government’s enticement for people to emigrate is a free android that will work as their personal servants.

However, some of these androids have returned to earth and must be killed. And the only way to distinguish between the androids and the humans is the lack of empathy in the androids–a lack that can be tested.

The plot, entails the main character, Rick Deckhard–an android bounty hunter–attempting to increase his bounty numbers so that he can buy some  real animals, instead of the “electric sheep” he now owns. Animals, he feels, encourage empathy in humans.

real animals, instead of the “electric sheep” he now owns. Animals, he feels, encourage empathy in humans.

I am not sure how I will squeeze this into our discussions of Brave New World and 1984. I am not sure if it can be squeezed into dystopic literature. Post-apocalpytic maybe–most of my kids have read or seen The Road and I am Legend–but it doesn’t really fit in with totalitarianism and its evils.

And then, maybe it won’t be all that important to the discussion anyway. Or better yet, maybe it’ll throw us all in a different direction completely.