Bonjour Tristesse (1958) was Jean Seberg’s second movie and her second one with the director Otto Preminger. The first, St. Joan, was a commercial flop and roundly criticized, as was Seberg’s performance in it. But it wasn’t really her fault: Preminger had let the nineteen year old naif vulnerably out on her own and she was unprepared. In fact, she had “won” the major role when, unknown to her, a neighbor had entered her name in a raffle that Preminger had famously set up to pick his St. Joan. The young girl from Iowa was in no way prepared to carry the load of Preminger’s version of George Bernard Shaw’ play.

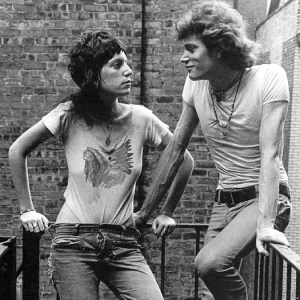

As a gesture of faith (and apology), Preminger cast Seberg in his next film, Bonjour Tristesse, based on the novel by Francois Sagan. Set in Paris and on the French Riviera, Seberg plays Cecile, the daughter of widowed playboy, Raymond (David Niven). Present day scenes are set in Paris and shot in black-and-white. As she flits from bohemian jazz club to high-society, pre-opera dinners, Seberg’s voice narrates a voice-over explaining her present ennui. Her memories, on the other hand–the events that have caused this sadness–take place on the French Riviera and are filmed in brilliant, sun-soaked color.

While on the Riviera, Raymond abandons his young, scatter-brained girlfriend for an old friend, the more sophisticated, more mature and more serious Anne Larson (Deborah Kerr). The two quickly get engaged and the new fiance is serious about curbing the young Cecile’s carefree life. It doesn’t end nicely.

The film is a bit dated now, but Seberg’s charm is still infectious and her waif-like beauty fetching. But again, the film was pilloried by the critics. She was a younger, spunkier Audrey Hepburn (whom Preminger had considered), but she simply did not have the acting experience…yet.

Her next film, The Mouse that Roared with Peter Sellers was much more warmly received, but by then Seberg had already decided on a life in France. (She had by then married François Moreuil, a French man she had met while filming Bonjour Tristesse.) Her career in France skyrocketed, and she soon became the female face of the French New-Wave–most notably starring in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless–and an international sensation.

But around then, her personal life was already under scrutiny by the FBI. Her financial support and vocal support of civil rights organizations and Native American organizations brought her to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover and the U.S. government, and she quickly became one of the more celebrated objects of the FBI’s COINTELPRO program. Its surveillance of her, its rumor-mongering, and its harassment were unceasing. And damaging.

In the end, it was too much, and Jean Seberg killed herself at the age of 40 in 1979. (Although even this is questionable, and the circumstances of her death are more than suspicious.)

In, Bonjour Tristesse, Seberg played a young woman stumbling under the weight of immense sadness (the sadness works much better in the novel.) Her career from that point on would likewise embrace much sadness but also much happiness. Celebrated in Europe, blacklisted (probably) in Hollywood, and hounded by the U.S. government, the young gamine-like beauty became a film icon…and a large footnote in the annals of FBI malfeasance.