Hugh MacDiarmid

Hugh MacDiarmid times 4

No’ wan in fifty kens a wurd Burns wrote

But misapplied is a’body’s property

And gin there was his like alive the day

They’d be the last a kennin’ haund to gi’e–

Croose London Scotties wi’ their braw shirt fronts

And a’ their fancy freen’s, rejoicin’

That Simlah gatherings in Timbuctoo,

Bagdad — and Hell, nae doot–are voicin’

Burns’ sentiments o’ universal love,

In pidgin English or in wild-fowl Scots,

And toastin’ ane wha’s nocht to them but an

Excuse for faitherin’ Genius wi’ their thochts.

A’ they’ve to say was aften said afore

A lad was born in Kyle to blaw aboot.

What unco fate mak’s him the dumpin’-grun’

For a’ the sloppy rubbish they jaw oot?

Mair nonsense has been uttered in his name

Than in ony’s barrin’ liberty and Christ.

If this keeps spreedin’ as the drink declines,

Syne turns to tea, wae’s me for the Zeitgeist!

Rabbie, wad’st thou wert here–the warld hath need,

And Scotland mair sae, o’ the like o’ thee!

The whisky that aince moved your lyre’s become

A laxative for a loquacity.

from “A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle” (lines 41-64)

Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978)

I got involved with this poem yesterday–a poem that I had long forgotten and had once loved dearly. A student of a friend of mine got in a bit of trouble with it and an art project he was doing. Just a few bad decisions.

Anyway, he was also out of his depth. The poem is nearly a hundred pages long, close to 3000 lines long, and written in the Scots dialect. In it MacDiarmid is bemoaning the present state of the world ( (“Rabbie, wad’st thou wert here–the warld hath need”) and calling for a certain national identity through a link to the past. And of course, as a early-twentieth century Scots poet, for Hugh MacDiarmid that link is Robert Burns.

I have always had an affinity for Burns. We share the same birthday and hit some of life’s milestones at the same time. But my introduction to him was from my father. My father was not a academic man; he had finished high-school and then out to work. But he had always been a wide-ranging and voracious reader. And he had a extraordinary memory for the poems he had read in school. Even in old age, he could recite poems that he had learned as a youth. The one I remember most was Robert Burns’ “To A Louse.” I remember it because it was his way of teaching humility, of teaching his children not to become too full of themselves. As a child, I loved the poem because it dealt with the humorous situation of spying a louse crawling in the wig of the elegant lady in front of him at church. Her social airs and superciliousness are punctured by the creature burrowing through her hair, unknown to her but visible to those in the pew behind.

But making fun of the rich lady was not the point. The lesson my father was offering was directed to us. Burns ends the poem with a prayer:

O wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

How perfect. How humbling. What an antidote to hubris!

I grew older, life went by, and I began reading seriously on my own. Suddenly, many of the pieces that my dad had recited came back into my life. And I took to Burns. (Even, his most anthologized–”To A Mouse, on Turning up her Nest with a Plough”–is a plea for empathy and understanding among all creatures, not only between humans, although that too certainly is implied. And it was there that I first recognized my father’s oft recited quote about the frequent ruinations of the “best laid plans.”)

In the section of Hugh MacDiarmid’s poem above, the speaker laments the caricature that has been made of Robert Burns over the years. The Burns’ suppers held around the world, the saccharine versions of “Auld Lang Syne” that punctuate each passing year (and that omit most poignant verses), the iconic being that he has been puffed up as, emptied of all the genius, vitality, politics and love that made him what he was.

Instead, MacDiarmid yearns for that great lover of liberty, the lover of life, the lover of Scotland. For instance, here is Burns simply singing the praises of his love–and stating that even death would not sever its bond:

Fair and lovely as thou art,

Thou hast stown my very heart;

I can die–but canna part,

My bonie dearie.

(“Ca’ the Yowes,” lines 20-24)

Here in 1792–70 years before the American Emancipation Proclamation–Burns writes about the anguish of a Senegalese leaving his home on a slave ship for the shores of Virginia. It is not the politics that are most important here (although they are important) it is the humanizing of a black man in 1792, the compassion and empathy for the slave’s lot. One can feel the slave’s weariness. One can feel his “bitter tear.”

The Slave’s Lament

It was in sweet Senegal that my foes did me enthral,

For the lands of Virginia,-ginia, O:

Torn from that lovely shore, and must never see it more;

And alas! I am weary, weary O:

Torn from that lovely shore, and must never see it more;

And alas! I am weary, weary O.

All on that charming coast is no bitter snow and frost,

Like the lands of Virginia,-ginia, O:

There streams for ever flow, and there flowers for ever blow,

And alas! I am weary, weary O:

There streams for ever flow, and there flowers for ever blow,

And alas! I am weary, weary O:

The burden I must bear, while the cruel scourge I fear,

In the lands of Virginia,-ginia, O;

And I think on friends most dear, with the bitter, bitter tear,

And alas! I am weary, weary O:

And I think on friends most dear, with the bitter, bitter tear,

And alas! I am weary, weary O:

But for me, it is the love poems that stand out. While some here in the 21st century might bash his promiscuity, I see it as his inordinate zeal and love of life. I believe the truth of his love poems–they are not simply lines to bed a willing lass–and I see them as some of the tenderest poems ever written. Here is one in which he has been played false…and his heart is breaking:

Ye banks and braes o’ bonnie Doon

Ye banks and braes o’ bonnie Doon,

How can ye bloom sae fair!

How can ye chant, ye little birds,

And I sae fu’ o’ care!

Thou’ll break my heart, thou bonnie bird

That sings upon the bough;

Thou minds me o’ the happy days

When my fause Luve was true.

Thou’ll break my heart, thou bonnie bird

That sings beside thy mate;

For sae I sat, and sae I sang,

And wist na o’ my fate.

Aft hae I roved by bonnie Doon

To see the woodbine twine,

And ilka bird sang o’ its love;

And sae did I o’ mine.

Wi’ lightsome heart I pu’d a rose

Frae aff its thorny tree;

And my fause luver staw the rose,

But left the thorn wi’ me.

From a boy in trouble in a friend’s school, to a poem by Hugh MacDiarmid, to Robert Burns, to my dad. The mind shifts easily from one thing to another. This is not a scholarly piece–my dad would find no worth in that–but a post about things I love and loved.

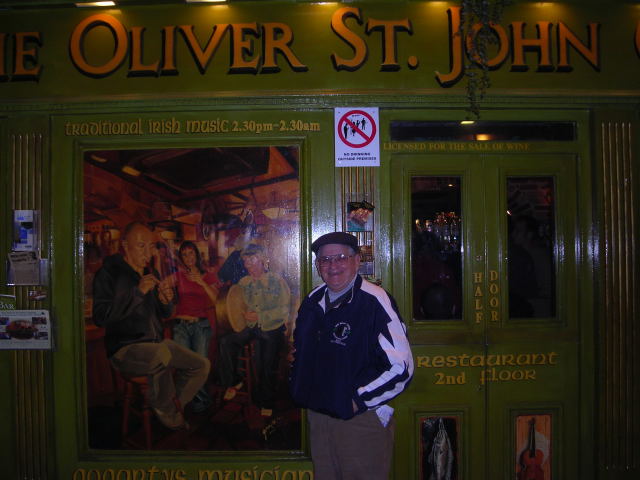

My father outside a pub in Dublin

![[graphics]_ABBA_2007_Marjane_Satrapi_(Persepolis_movie)_[www.ABBAinter.net]](https://jpbohannon.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/graphics_abba_2007_marjane_satrapi_persepolis_movie_www-abbainter-net.jpg?w=676)