The old man laughed indulgently, holding in check a deeper, more explosive delight. “Rome was destroyed, Greece was destroyed, Persia was destroyed, Spain was destroyed. All great countries are destroyed. Why not yours. How much longer do you think your own country will last? Forever? Keep in mind that the earth itself is destined to be destroyed by the sun in twenty-five million years or so.” Catch-22, Joseph Heller

I spent the day yesterday in The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Part of a photographic-mural, the woman above looks over you as you enter the Mid-Eastern galleries; her almond eyes seem those of a goddess, knowing, far-seeing, beautiful. And then one wonders, what might she have actually seen in her life. What is her life like? Is she still alive? Still in her native land?

Afterwards, when I was thinking about the various galleries in the museum that I had lingered in, I was struck by this: I had visited Persia, Greece, Rome, Mexico, Egypt–high-points of human civilization and, in 2012, flashpoints of suffering and discontent, violence, confusion and uncertainty.

The poets are helpful here–though not necessarily hopeful–and the photos I took seemed to have their own poetic soundtrack in my mind. Here is Yeats:

THE SECOND COMING

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: a waste of desert sand;

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Wind shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

And then here’s Shelley on the same tack although not as apocalyptic:

Ozymandias

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown

And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed.

And on the pedestal these words appear:

`My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away”.

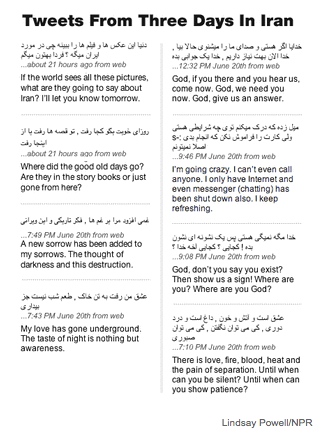

“If the world sees all these pictures, what are they going to say about Iran? I’ll let you know tomorrow.”

“Where did the good old days go? Are they in the story books or just gone from here.”

“A new sorrow has been added to my sorrow. The thought of darkness and this destruction.”

“My love has gone underground. The taste of night is nothing but awareness.”

“God, if you’re there and you hear us, come now. God, we need you now. God, give us an answer.”

The Persians have long been known for their poetry. Lush, emotional, spiritual and clear. The poems to the left were tweets sent during the contested elections in Iran in June 2009. It is evidence of my theory that poetry–in fact all written expression– is an innate desire, beaten out of children by well-meaning but misinformed teachers. While the immediate world seems to be spinning out of control (see Yeats’ spiral above), these young Iranians find the need to put their thoughts on paper–or onto some kind of device in 140 characters or less.

GREECE — Poor Greece, so beautiful, so lovely, and so fragile to economic decisions that seem far removed from the people themselves.

Headless Statue by Kyriakos Haralambdis

(translated by Kimon Friar). Hellenic Quarterly, Summer, 2000.

I have heard that your head

has been sent as a sacred skull to Constantinople .

.

Byzantine emperors manfully

placed you in red and gold.

The star of God’s Holy Wisdom

studies you and covers you.

And you, a woman, in a late hour

open your closed eyelashes.

You look fruitlessly, for we have gone away on a journey,

and you call out to us “come to my guest room.”

But we, artful head, seek your whole body,

in a city that resembles you. If we succeed,

we shall call this bone our own.

Poor city, ten years in bed,

without the lamp stead at our head,

as headless and cold as lead.

I don’t want to be distressed by seeing you, my bird.

I know you are absent, all has been heard.

Your skill in a huge box

embellished with small serpents and small stars

all made of paper, seed of manliness

travelled around the world to be placed

in houses of ill repute and cabarets

in the sky of the city where it reigned.

You who hear me, do not misunderstand me.

Such things serve the natural remembrance of mortals,

others the cleansing of memory.

MEXICO— one murder is always too many. Poor Mexico is far beyond too many, far beyond human understanding, far beyond humanity.

“And every time they opened, it was night and the moon, while they climbed the great terraced steps, his head hanging down backward now, and up at the top were the bonfires, red columns of perfumed smoke, and suddenly he saw the red stone, shiny with the blood dripping off it, and the spinning arcs cut by the feet of the victim whom they pulled off to throw him rolling down the north steps. With a last hope he shut his lids tightly, moaning to wake up. For a second he thought he had gotten there, because once more he was immobile in the bed, except that his head was hanging down off it, swinging. But he smelled death, and when he opened his eyes he saw the blood-soaked figure of the executioner-priest coming toward him with the stone knife in his hand. He managed to close his eyelids again, although he knew now he was not going to wake up, that he was awake, that the marvelous dream had been the other, absurd as all dreams are-a dream in which he was going through the strange avenues of an astonishing city, with green and red lights that burned without fire or smoke, on an enormous metal insect that whirred away between his legs. In the infinite he of the dream, they had also picked him up off the ground, someone had approached him also with a knife in his hand, approached him who was lying face up, face up with his eyes closed between the bonfires on the steps.” from “The Night Face-Up” by Julio Cortazar

ROME–And on a happier note, this from Catallus:

–5–

Let’s you and me live it up, my Lesbia,

and make some love, and let old cranks

go cheap talk their fool heads off.

Maybe suns can set and come back up again,

but once the brief light goes out on us

the night’s one long sleep forever.

First give me a kiss, a thousand kisses,

then a hundred, and then a thousand more,

then another hundred, and another thousand,

and keep kissing and kissing me so many times

we get all mixed up and can’t count anymore,

that way nobody can give us the evil eye

trying to figure how many kisses we’ve got.

I spent the majority of my visit in the Greco-Roman-Estruscan galleries, though I took a guided tour through the Meso-American gallery and the Southwest American gallery. These dealt with the ancient peoples of the Yucatan peninsula and the southwest corner of what is now the United States. Current theories claim that these wide reaching people actually traded and influenced one another over the centuries: the Incans, the Mayans, the Hopi, the Pueblo. Yet they too–the Mayan cities seem so much more advanced than the Athens, Roman, Cairo counterparts–all were subsumed by human violence and human greed.

It is an impressive museum, The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. But it left me feeling a bit desperate…a little hopeless…a little sad. Sad, except for the women in the photographic mural whose eyes are so beguiling. Perhaps the poets are right all along, and it is beauty and love that will carry us through.