My mother died yesterday.

She was a simple, quiet, sweet woman whose last few months were horrible. And while it might sound cold-hearted, I can honestly say she is better off today than she was the past few weeks. For better or worse, at least she is now at peace.

And while I have a good number of siblings and a large network of friends and relatives with whom to share the loss, privately I turn to Art with a capital “A.”

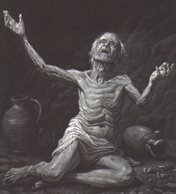

The picture above is of a painting by Pieter Brueghel. Entitled Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, it depicts the legendary fall of Icarus, who (in one story) famously disobeyed his inventive father and flew too close to the sun. The sun melted the wax holding together the wings that his father had fashioned, and he crashed into the sea. Through the ages, Icarus has become a two-sided symbol for artists: he is either a symbol of blatant disobedience akin to Eve or Pandora or Deidre or a symbol of great striving, of “flying to the sun,” of grabbing all the gusto one can. I usually lean to this second interpretation and see Icarus as an example of risking it all in pursuit of one’s dreams.

Anyway, this painting is one of my very favorites because

detai from painting: Icarus’ two legs in the water

Brueghel has depicted this grand, mythic tragedy as happening amidst the pedestrian goings-on of daily life. If you look closely, you can see Icarus’ legs darting into the water in the right hand corner of the canvas. If you are not looking for them –and did not have the title of the painting to clue you toward Icarus–you might miss them entirely in the busyness of the entire painting. There is a shepherd, a ploughman, a single fisherman, a stately ship and a far-away city, but the boy falling out of the sky barely registers on their existence.

A very famous painting, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus also has been the subject of several poems, most notably by Auden and William Carlos Williams.

Below is W.H.Auden’s poem about the painting which now hangs in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Artes Belgique in Brussels:

Musée des Beaux Arts by W. H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

So yesterday, after the mortician took my mother’s body away, after my brother and sisters and I cleaned out her personal effects and donated her clothes to the needy, I drove away and stopped at a convenience store for a sandwich. The store was extra crowded, there was a particularly annoying man in line, and the cashier herself was particularly surly. I wanted to yell to them, to say, “Hey, don’t you know my mother just died?!” But of course I didn’t and of course they couldn’t have. They were simply going about their normal Saturday routines.

Instead I thought of Brueghel and Auden and Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.

Yet, Auden missed another part of the equation. While it is true that the world goes on despite, and during, moments of personal tragedy, it also does the same in moments of great personal triumph. We tend to think that much of this existence is about us, about our heartbreaks and our victories–and very little of it really is.

Anyway, my world is different today than it was yesterday. I must meet with siblings to arrange funeral services, arrange affairs at work for missed time, try to find a wearable suit for the funeral…and the entire time the great big world will go spinning along, unaware of what any of us are dealing with.

As Auden said, “they were never wrong,/The Old Masters.”

Margaret (Peggy) Bohannon

nee McNeila

1929-2012

Requiescat in pace