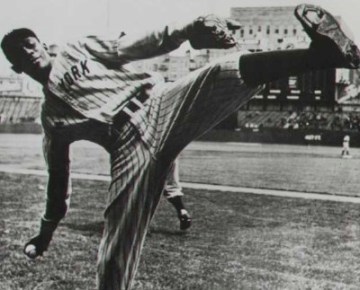

I gave my students a poem today and asked them to wriggle around inside it and tell me everything they found in there. The poem I gave them was “The Pitcher” by Robert Francis. I was hoping there were some baseball players in the class, but none of them had played much past little league. But many of them were fans. And I believe they achieved a pretty good literal reading–how a pitcher in baseball depends greatly on being misunderstood, at aiming at something he didn’t seem to be aiming at, at avoiding the obvious and varying the avoidance. We went through it line by line, describing what aspect of a pitcher’s performance was being described. One student thought that maybe it might even be, in his words, “about a pitcher and maybe about a non-conformist.” That was interesting. He knew what he meant but was having trouble working himself through it. And then one student, somewhat self-doubting, said that he too saw the poem dealing with a baseball player and something else. But for him, that something else was “a poet.” He went on to say that a poet’s deception was that instead of saying something was brown, he would say something was like the “leaves of autumn.” Much like a pitcher’s throw looks like its coming one way but then intentionally breaks another. A part of him believed that he was really off-the-mark but, to his credit, he forged on. And he was pretty good. In fact, in the past, after a class has seen this poem, I ask them–as they are leaving–to think again about “The Pitcher” when they get home, but this time to think in terms of a poet and the poet’s craft, to think about the similarities between what some pitchers and some poets attempt to do. And the next days’ discussions are often quite good. But today’s student was the first ever to go there without my prompting. And that’s a pretty cool thing.

The Pitcher by Robert Francis

His art is eccentricity, his aim

How not to hit the mark he seems to aim at,

His passion how to avoid the obvious,

His technique how to vary the avoidance.

The others throw to be comprehended. He

Throws to be a moment misunderstood.

Yet not too much. Not errant, arrant, wild,

But every seeming aberration willed.

Not to, yet still, still to communicate

Making the batter understand too late.