“When I was a child I truly loved:

Unthinking love as calm and deep

As the North Sea. But I have lived,

And now I do not sleep.”

— John Gardner, Grendel

“In the world sloth … is the sin that believes in nothing, cares for nothing, seeks to know nothing, interferes with nothing, enjoys nothing, loves nothing, hates nothing, finds purpose in nothing, lives for nothing and remains alive only because there is nothing it would die for. We have known it far too well for many years.”

Dorothy Sayers, “The Other Six Deadly Sins”

“And there we lay. Not speaking, not stirring until finally I moved my face across hers, and kissed her. And at last the age-old ritual possessed us, and I bit and tore and held her, round and round. . . . Later there would be time for the pain and pleasure lust lends to love. Time for body lines and angles that provoke the astounded primitive to leap delighted from the civilised skin, and tear the woman to him. There would be time for words obscene and dangerous.”

Josephine Hart, Damage

“One night I accidentally bumped into a man, and perhaps because of the near darkness he saw me and called me an insulting name. I sprang at him, seized his coat lapels and demanded that he apologize. He was a tall blond man, and as my face came close to his he looked insolently out of his blue eyes and cursed me, his breath hot in my face as he struggled. I pulled his chin down sharp upon the crown of my head, butting him as I had seen the West Indians do, and I felt his flesh tear and the blood gush out, and I yelled, “Apologize! Apologize!” But he continued to curse and struggle, and I butted him again and again until he went down heavily, on his knees, profusely bleeding. I kicked him repeatedly, in a frenzy because he still uttered insults though his lips were frothy with blood. Oh yes, I kicked him! And in my outrage I got out my knife and prepared to slit his throat, right there beneath the lamplight in the deserted street, holding him by the collar with one hand, and opening the knife with my teeth — when it occurred to me that the man had not seen me, actually; that he, as far as he knew, was in the midst of a walking nightmare! And I stopped the blade, slicing the air as I pushed him away, letting him fall back to the street. I stared at him hard as the lights of a car stabbed through the darkness. He lay there, moaning on the asphalt; a man almost killed by a phantom. It unnerved me. I was both disgusted and ashamed.”

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

“In this dream, though, he burned with desire for a woman. It wasn’t clear who she was. She was just there. And she had a special ability to separate her body and her heart. I will give you one of them, she told Tsukuru. My body or my heart. But you can’t have both. You need to choose one or the other, right now. I’ll give the other part to someone else, she said. But Tsukuru wanted all of her. He wasn’t about to hand over one half to another man. He couldn’t stand that. If that’s how it is, he wanted to tell her, I don’t need either one. But he couldn’t say it. He was stymied, unable to go forward, unable to go back.”

Haruki Murakami

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage

“I dreamed my lips would drift down your back like a skiff on a river.” William H. Gass “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country.” illustration 2014 by jpbohannon

Because of some administrative hic-cough, I was sent two copies this weekend of the same book: William H. Gass’ In the Heart of the Heart of the Country. I had not heard of it, although I recognized the name of the author (and immediately confused him with the novelist, William Gaddis). Having two copies, I gave one to my friend Tim Dougherty, who very well may be the best-read person I know.

Here was the text he sent me later that day:

John,

Thanks so much for the book. Gass’ “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” is a seminal postmodern short story. The collection is one of my favorites, and the new edition blows my flea market paperback out of the water. And now I can throw that one away!

Who’d have thunk it.

So, on my train-ride to work the next morning, I read “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country.” The story is the final piece in a collection of the same name that includes two novellas and three short stories, but I went to the last story right away.

And it is everything that Tim’s message had intimated.

First it is broken into short chunks with headings such as “People” or “Weather” or “Places” or “My House.” It is a sort of stream of consciousness, movie-like postcard of a town in Indiana and the people who live there, and at the same time it is a self-portrait of the narrator who has lately lost love (through death or separation I am unsure) and who is both crushed and buoyed by the vastness of the Midwest.

But it is the language that is so remarkable, that stands out yet does not make a show of it. There are exquisite lists. This is the narrator describing a neighbor’s basement:

...stacks of newspapers reaching to the ceiling, boxes of leaflets and letters and programs, racks of photo albums, scrapbooks, bundles of rolled-up posters and maps, flags and pennants and slanting piles of dusty magazines devoted mostly to motoring and the Christian ethic. I saw a bird cage, a tray of butterflies, a bugle, a stiff straw boater, and all kinds of tassels tied to a coat tree.

And here he is describing the town itself in a section called “Vital Data”:

There are two restaurants here and a tearoom. two bars. one bank, three barbers, one with a green shade with which he blinds his window. two groceries, a dealer in Fords. one drug, one hardware, and one appliance store. several that sell feed, grain, and farm equipment. an antique shop. a poolroom. a laundromat. three doctors. a dentist. a plumber. a vet. a funeral home in elegant repair the color of a buttercup. numerous beauty parlors which open and shut like night-blooming plants. …

But it is his memories of the lost love and of lost childhood, the feelings of being trapped in a dying world, and his description of the decadent monotony of small town life that resonates the most, in which the fiction writer becomes one with the poet, and where the language becomes as integral to the story as the story itself, where inside and outside, the public and the private, that which is thought and that which is felt, all merge into one.

It is majestic and memorable.

And I can’t wait to finish the rest of the collection.

Coincidences are no more than that, though I am very well aware of the research on them. (Freud once stated that there were no such things as accidents, but I believe coincidences to be a lesser, less conscious form of accident. In the latter, the subconscious is directing you towards what might seem to be a accident but is actually rooted in one’s memory, suppressed or on the surface. Coincidence, on the other hand, is simply the awareness of a multiplication of events, of which one wasn’t completely cognizant or prepared for beforehand.)

So anyway, I attended an intense two-week workshop on education-on assessments and feedback and good old Bloom’s taxonomy. However, much of it was rooted in the teachings of Augustine–and much of the feedback I received referenced Dante.

Before the workshop, however, I had bought a book, Echo’s Bones by Samuel Beckett. I knew it was something I would need to concentrate on–a 52 page short-story, accompanied by 58 pages of annotations, and complete with an introduction, copies of the original typescript, letters from Beckett’s publishers, and a bibliography. This was not simply reading a short story, but sort an academic adventure. The type of diversion I hadn’t had in a while.

And so I waited until my Augustinian-laced workshop was over.

And then I began reading. After I got through the introduction and into the story I began to smile. It was Augustine all over again with a large dollop of Dante. In the first three pages alone there are five allusions to Augustine and four allusions to the Divine Comedy. And the main character, Belacqua, is given the nickname, Adeodatus–the name of Augustine’s illegitimate son.

So why all this hubbub about a short story that was written more than eighty years ago? Well, Beckett had written a collection of interrelated short stories entitled More Pricks than Kicks. Right before publication, however, his publisher asked if Beckett would add a final story to the collection, to fatten it up, so to speak.

Beckett agreed, except there was one problem. All the characters in the collection were now dead. And so Beckett wrote “Echo’s Bones,” which told the story of the dead Belacqua’s return to life in his short interim between death and eternity. The publisher rejected the story, stating that it was too dark, too odd, and that it would make readers shudder. And so More Pricks than Kicks was published as it was originally intended, and “Echo’s Bones” was assigned to the crypt of oblivion. Until now.

The title refers to the mythological figure Echo, who tragically fell in love with Narcissus. (He was never a good catch for any woman. Too much competition with himself alone!) Anyway, when she died, all that was left were her bones and her voice. Thus, we have “Echo’s Bones.” If the editors had only known how perfectly the story’s title would foretell the nature of Beckett’s future work: a work of spotlighted voices–often disembodied (Krapp’s Last Tape), often body-less (HappyDays), and often flowing in a rushing stream (Ponzo’s soliloquy in Godot).

The plot is secondary to the wordplay, the erudition, the humor, and Beckett’s world view. Quickly: the dead Belacqua suddenly finds himself on a fence in a empty Beckettian landscape. A woman arrives and brings him to Lord Gall, a giant of a man with a paradisaical estate which he will lose because he is sterile and lacks a male heir. He convinces Belacqua to bed his wife, in hope of an heir, but–in a twist of telescoped time–the woman gives birth to a daughter. The story concludes with Belacqua conversing with his own grave digger (from an earlier story) and searching his own coffin for his body. The story ends with a familiar phrase in Beckett’s work and letters: “So it goes in the world.” These are the last words of “Echo’s Bones,” but they are also the last words of “Draff,” the final story in the version of More Pricks than Kicks that was ultimately published. A phrase that Beckett had picked up from the Brothers Grimm story “How the Cat and the Mouse Set up House,” it is a phrase that encapsulates Beckett’s life view and one that he used often even in his personal correspondence.

While I respect and love Beckett’s drama, I particularly enjoy his early fiction. Still under the influence of Joyce, Beckett, at this time, was full of his verbal powers, delighting in the wordplay, and confident in his free association. It is always, for me, a treat to read.

Last week, at a “workshop/institute/conference” I am attending for a few weeks this summer, Christian Talbot spoke to us about “chaos theory” and the creative need for tension in any collaboration. The theory goes, simply, that any collaboration must begin with chaos. Butting against each other is a conflict of ideas–and often a conflict of personalities. As the collaborative project goes forward, this tangle of conflicts begins to stretch out into a diametric pattern of varying depths with one single thrust being countered by another until ultimately the collaborators move directly towards the goal. Talbot insisted that the initial conflict is essential, even positing that if there is no conflict the final outcome can not be as robust as it possibly could have been.

The man next to me, Emanuel DelPizzo–an excellent musician and leader of a twelve piece R&B band–cited the Beatles as evidence of this tension. He cited the arguing and fighting and one-up-manship that often went on during a Beatles’ recording session and the perfection of the result. We both talked about the tensions that can arise within bands and the trust that one ultimately has to place in one’s fellow players.

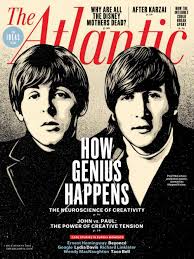

And then, this coincidence ensued. The following day, as we were moving from one task to the next, I walked over to a quiet part of the room where there were a pile of recent magazines. On the top was a copy of the July/August issue of The Atlantic. A picture of Lennon and McCartney on the cover caught my eye. It is The Atlantic’s “IDEA issue.” (Though I would think it would want all its issues to be “idea issues”!) Anyway, the essay was touted on the front cover as–“John vs. Paul: The Power of Creative Tension.” This is exactly what Christian was talking about yesterday and was the very example that Manny had offered.

And then, this coincidence ensued. The following day, as we were moving from one task to the next, I walked over to a quiet part of the room where there were a pile of recent magazines. On the top was a copy of the July/August issue of The Atlantic. A picture of Lennon and McCartney on the cover caught my eye. It is The Atlantic’s “IDEA issue.” (Though I would think it would want all its issues to be “idea issues”!) Anyway, the essay was touted on the front cover as–“John vs. Paul: The Power of Creative Tension.” This is exactly what Christian was talking about yesterday and was the very example that Manny had offered.

The essay by Joshua Wolf Shenk is entitled “The Power of Two” and immediately attempts to diffuse the prevalent idea, that Lennon wrote his songs and McCartney wrote his. Debunking the idea of the solitary genius–so prevalent in popular lore and imagination–Shenk states that the two very different friends bounced off and into each other in order to create what they did.

And the two were in fact very different. Shenk quotes Lennon’s first wife, Cynthia, who said, “John needed Paul’s attention to detail and persistence, and Paul needed John’s anarchic, lateral thinking” (p. 79). And this symbiosis continued to fuel their creativity. (One could seriously argue that nothing they wrote separately afterwards attains the same level as their “collaborative” effort.) I was surprised to hear that McCartney, more sure of himself, was the one likely to take criticism badly, while Lennon was more open to others’ opinions and more amenable to change. Shenk attributes this to McCartney’s perfectionism.

Shenk cites Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the White Album as an example of the collaborative conflict that the two would cycle through–both jockeying for dominance, both vacillating between the alpha male and the diplomat. Sgt. Pepper’s showed the two working closely together. For example, they volleyed Lewis Carroll-like phrases back and forth to each other to write “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and they simply fused two separate songs together to create the masterpiece “A Day in the Life.” Lennon called the White Album, “the tension album,” but as Shenk writes:

“Despite the tension–because of the tension–the work was magnificent. Though the White Album recording sessions

were often tense and unpleasant ([EMI engineer Geoff] Emerick disliked them so much that he flat-out quit),

they yielded an album that is among the best in music history.” (p. 85)

And when they did write separately they egged each other on. Lennon scoffed at MccCartney’s original opening of “I Saw Her Standing There” and fixed it. McCartney softened the raw pain of John’s original version of “Help,” adding a counter-melody and harmony. And even when they were apart, they were bouncing off each other. John wrote “Strawberry Fields” –about a nostalgic spot of his boyhood Liverpool–in late 1966 and the band recorded it on December 22 of that year. Seven days later McCartney arrived with a song he had written about another iconic Liverpool spot, Penny Lane. Shenk quotes McCartney saying that John and he often played this answer and call type of thing–sort of the middle ground of that chaos theory illustration.

Any one who knows the story of The Beatles, knows roughly the story of their falling out and “disbanding.” And yet, Shenk returns to the final concert–the rooftop performance on top of Apple Studios–and sees the old collaboration–both the conflict and the trust–still evident. Standing in the positions that they had taken in the early days, the two rely on and trust each other, even through some miscues and misstakes, to present a concert that was both memorable and historic.

While it is fun, to travel through the Lennon and McCartney’s creative process–and through their times in the studio–this is not really the focus of Shenk’s article. He is attempting to show the workings of creative pairs. He lists creative pairs from Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ralph Abernathy to Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Shenk enumerates McCartney and Lennon’s differences and their tensions as well as their friendship and trust as being the forge in which their art was struck. As Shenk states:

John and Paul were so obviously more creative as a pair than as individuals,

even if at times they appeared to work in opposition to each other. …The essence

of their achievements, it turns out , was relational. (p.79)

And that achievement is timeless.

Shenk, Joshua Wolf. “The Power of Two” The Atlantic. (July/August 2014, pp. 76-86)

The Book Review of the Sunday New York Times this week (July 20, 2014) focused on contemporary poetry. It reviewed five books of contemporary poetry and featured an essay by David Orr entitled “On Poetry.” The front cover was a whimsical drawing with archaic poetic terms such as “forsooth,” “twas,” “alas-alack” and “thither” graffitied onto walls, suit jackets and boots. And on page 4, where the Book Review often introduces the matter of chief focus in that particular issue, there is a brief recap of New York Times’ poetry criticism through the years.

The four paragraph piece remembers the 1937 review of Wallace Steven’s The Man with the Blue Guitar, a review of John Berryman’s 77 Dream Songs in 1964, a 1975 piece on John Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, and a 1981 review of Sylvia Plath’s Collected Poems (18 years after her death). And it was the review of the Steven’s piece that caught my eye. The reviewer–Eda Lou Walton–stated that “the skill of these plucked and strummed-out improvisations proves him again the master of the most subtle rhythmical effects.”

And so of course, I had to pull from my shelf my copy of Wallace Stevens’ Collected Poems and looked to “The Man with the Blue Guitar.” Actually the title refers to both a particular poem and the book in which it was contained. The individual poem is the piece that attracted the world’s attention. It is a long piece, thirty-three sections of between four and sixteen couplets. Stevens claimed that he was inspired by Picasso’s painting Old Man with a Guitar. (Later David Hockney would paint a series of works inspired both by Picasso’s painting and Steven’s poem.)

What is surprising is that the poem is so much more a “shattered” portrait than Picasso’s piece. Picasso’s Man with a Blue Guitar belongs (not surprisingly) to his Blue Period, but more importantly comes several years before he is influenced by African art and–with Georges Braque–invents Cubism. It is the cubism–and his art that follows–that is “shattered,” that most resembles the large schisms and small fractures running through society and which most resembles the world of Stevens’ guitar. In fact, despite his referencing Picasso in the poem itself, it seems as if Stevens’ poem is more in tune with Hockney’s painting (impossible since it was painted in 1982, forty-five years after Stevens’ poem.)

I

The man bent over his guitar,

A shearsman of sorts. The day was green

They said, “You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.”

The man replied, “Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.”

And they said then, “But play you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,

A tune upon the blue guitar

Of things exactly as they are.”

And so, we have the “man with the blue guitar” refusing to tell things as they are–or perhaps unable to. Or is he implying that even the imagination, the creative faculty, is unable to depict “things as they are”? Or is this phrase “things as they are” simply a coded phrase for the physical world–and guitar and the player are able to sing of what is behind that physical world. And yet his audience seems somewhat philistine–they are slow to understand. For them, “Day is desire and night is sleep” and “the earth for us is flat and bare/there are no shadows anywhere.” And yet, we–and the player of the blue guitar–know that if nothing else, the 20th century has taught us that shadows are everywhere.

The poem has often been depicted as a tension between the guitarist and his audience, between the imaginative truth and the surface perceptions. I believe it shows the failure of the audience to see deeper, a failure of the audience’s imagination. Modern life–and this is surely not original with Stevens–is deadening and routine, and we need the players of the blue guitars to break us out, to center our focus on the more important things than mere survival.

Because of copyright issues, the entire poem is not available on line. (Though I am sure some clever computer user has found it somewhere.) But it is worth finding. It is a Whitman-esque explosion of images and thoughts and debate and sound.

I had forgotten about it–and about where and who I was when I first read it–and so am grateful for last Sunday’s paper which mentioned it a tiny corner of a large section. Sunday’s paper was the blue guitar that sent me re-reading and re-thinking.

Here are the first six sections of the poem:

I

The man bent over his guitar,

A shearsman of sorts. The day was green

They said, “You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.”

The man replied, “Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.”

And they said then, “But play you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,

A tune upon the blue guitar

Of things exactly as they are.”

II

I cannot bring a world quite round,

Although I patch it as I can.

I sing a hero’s head, large eye

And bearded bronze, but not a man,

Although I patch him as I can

And reach through him almost to man.

If to serenade almost to man

Is to miss, by that, things as they are,

Say that it is the serenade

Of a man that plays a blue guitar.

III

Ah, but to play man number one,

To drive the dagger in his heart,

To lay his brain upon the board

And pick the acrid colors out,

To nail his thought across the door,

Its wings spread wide to rain and snow,

To strike his living hi and ho,

To tick it, tock it, turn it true,

To bang it from a savage blue,

Jangling the metal of the strings…..

IV

So that’s life, then: things as they are?

It picks its way on the blue guitar.

A million people on one string?

And all their manner in the thing.

And all their manner, right and wrong,

And all their manner, weak and strong?

The feelings crazily, craftily call,

Like a buzzing of flies in autumn air,

And that’s life, then: things as they are,

This buzzing of the blue guitar.

V

Do not speak to us of the greatness of poetry,

Of the torches wisping in the underground,

Of the structure of vaults upon a point of light.

There are no shadows in our sun,

Day is desire and night is sleep.

There are no shadows anywhere.

The earth, for us, is flat and bare.

There are no shadows. Poetry

Exceeding music must take the place

of empty heaven and its hymns,

Ourselves in poetry must take their place,

Even in the chattering of your guitar.

VI

A tune beyond us as we are,

Yet nothing changed by the blue guitar;

Ourselves in the tune as if in space,

Yet nothing changed, except the place

Of things as they are and only the place

As you play them, on the blue guitar,

Placed, so, beyond the compass of change,

Perceived in a final atmosphere;

For a moment final, in the way

The thinking of art seems final when

The thinking of god is smoky dew

The tune is space. The blue guitar

Becomes the place of things as they are,

A composing of senses of the guitar.

(27 more sections yet to come)

On two separate occasions, my friend Jim has stopped the car on the way to dropping me off at the train station to finish listening to Neil Young’s “Country Girl.” For him, he remembers a particular girlfriend who broke up with him oddly and for whom this song is a reminder. For me, I remember hitchhiking across Canada, sitting on the floor of a Winnipeg record store (Winnipeg was where Neil was born) and copying down the chords from a fake book. For both of us, the song is a lot more than just music and lyrics.

Jim and I often do this. The “where” and “when” of a song, the lives we were leading, the dreams we were having, the people we were hanging with, are as much a part of a song than any of its recordable parts. And for each of us, those elements are different and recall a thousand different memories.

This is the basis of Rob Sheffield’s memoir Love is a Mixed Tape. Sheffield–a writer for Rolling Stone–writes about his late wife and himself through the skeleton of different mixed tapes. The sub-title of the book is Life and Loss, One Song at a Time, and this is exactly it: the life of a man and the life of the woman he loved told through the soundtrack of their lives. And, for some of us, it is our lives as well.

Sheffield starts off going through his dead wife Renee’s belongings and discovering several of her mixed tapes, spending a sad night listening to the first one–The Smiths, Pavement, 10,000 Maniacs, R.E.M., Morrissey, Mary Chapin Carpenter, and Boy George among them–commenting on her choices and their lives together when she made them. He talks about the various types of mixed tapes: the Party Tape, the “I Want You” tape, the “We’re Doing It” tape, the Road Tape, the “You Broke My Heart and Made Me Cry” tape, the Walking Tape, the Washing the Dishes tape. etc. From here he sets up his frame work–the tapes of our lives are the record of of our lives.

And so he begins. He starts by dissecting his own tapes, chronologically starting from a mixed tape he made as a thirteen-year old for an 8th-grade dance through his first romance and subsequent break up to his meeting Renee, their courtship and marriage, her sudden death and his struggles to continue on afterwards. It is poignant and wise writing about love and loss and survival.

Many of the bands I had never heard of–both he and his wife were music writers–but the pure affection and excitement that these two shared for new and old music was infectious. He was an Irish-Catholic boy from Boston who grew up on Led Zeppelin, the J. Giles Band, and Aerosmith; she, an Appalachian girl from West Virginia as familiar with George Jones and Hank Williams as she was with the punk bands she adored. Together they made a likeable pair. And their knowledge and love for music is wide and inclusive.

Sheffield met his wife in 1989 and she died in 1997. Their relationship lasted most of the 1990s and this is where Sheffield the music critic is at his best. His analysis of that decade, where the music was going and what it was doing is trenchant: he understands the phenomenon of Kurt Cobain, the importance of female empowerment in 90s’ music, the resurgence of guitar bands. (His discussion of Cobain’s late music/performances as the plights and pleas of a pained husband is unique and insightful and bittersweet.)

The naturally shy Sheffield–understandably–reverts into himself after his wife’s death. He is more and more asocial, awkward and uncomfortable. He writes eloquently about the pain of loss, of the condition of “widow-hood,” of unexpected kindness, and of the haunting of the past. Sadly, music–which once was his buoy in life–is pulling him down, especially the music that he and Renee had shared. In the end, however, it is music that pulls him together as well. He moves out of the south and to New York City, he reconnects with friends, makes new friends, and–of course–starts seeing and listening to new bands.

This is the tape–the last in the book–that Sheffield made when moving into a new apartment in Brooklyn, December 2002.

Love is a Mixed Tape was recommended to me by a friend, Brendan McLaughlin. Brendan was born in the mid-80’s, not long before Sheffield and his wife first met. He is connected much more closely to the music than I am, and I am sure that he recognized a lot more of the bands and songs cited than I did. But that is the great thing about Sheffield’s memoir: you don’t have to be completely tuned into what he is listening to, just to what he is saying.

And what he says is true.

The Official Web Site of LeAnn Skeen

Grumpy younger old man casts jaded eye on whipper snappers

"Here is my secret. It is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.."- Antoine de Saint Exupéry

Of writing and reading

Photography from Northern Ontario

Musings on poetry, language, perception, numbers, food, and anything else that slips through the cracks.

philo poétique de G à L I B E R

Hand-stitched collage from conked-out stuff.

"Be yourself - everyone else is already taken."

Celebrate Silent Film

Indulge- Travel, Adventure, & New Experiences

Haiku, Poems, Book Reviews & Film Reviews

The blog for Year 13 English students at Cromwell College.

John Self's Shelves

writer, editor

In which a teacher and family guy is still learning ... and writing about it

A Community of Writers

visionary author

3d | fine art | design | life inspiration

Craft tips for writers