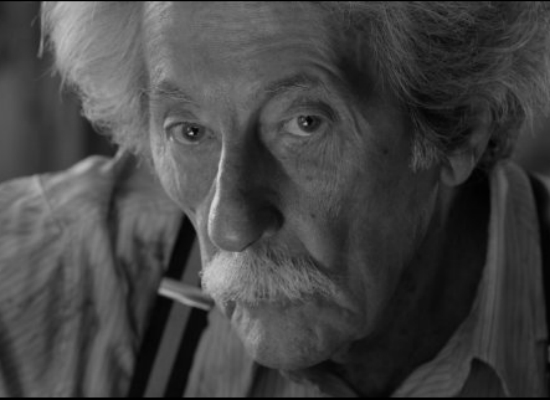

Trueba’s The Artist and the Model is the art of film raised to the highest level. Its story is poignant, its intelligence is palpable, its cinematography is mesmerizing, its acting is subtle and powerful and its beauty is breathtaking. And in a film that addresses life and art and beauty and work, it is the very face of the artist Marc Cros (Jean Rochefort) that comes to represent them all, a face that Trueba closes in on with love and craftsmanship, a face that seems to contain the very themes of the film itself.

An elderly sculptor (Rochefort) has isolated himself in a small village apart from the business of war in Occupied France during World War II. One day, his wife (Claudia Cardinale) discovers a Spanish refugee (Aida Folch) sleeping rough and washing herself in the village’s fountain, She brings the girl home to her husband to be his next (and last) model, to be the muse for him that she had once first been.

In exchange, the young woman, Mercè, receives room and board and a salary. Awkward at first, their relationship–the artist and the model– grows into a symbiotic one: she inspires the sculptor and he transforms her into his masterpiece. In their life together, she is joyous and he is crotchety. She is young and he is wise. She is involved in the war and he is trying to keep it at bay.

The film is shot in black and white. But to merely say “black and white” does not capture the luminous beauty of the photography. Each scene has a shimmering silver light that imbues the film with both beauty and gravitas. Each scene seems as if a Richard Avedon portrait had come to life. I do not exaggerate when I say that this may be the most beautiful film I have ever seen.

The slow rhythm of the film may be off-putting to some, but it should not. We are watching something very special here. The creative process has always been a difficult one to portray, and a slew of films have done it badly. But not this. This comes as close as is probably possible in capturing the artistic process: idea, incubation, trial, and execution.

And aside from our watching the process, there is the sculptor’s instruction for his model. At one point, he tells her his version of creation. God, he says, having created the beauty of the universe, wanted someone to share it with and so he created woman. (He believes the female body and olive oil are God’s greatest creations.) Together, God and the woman, had a son Adam.

At another time, he takes a scribbled pen-and-ink drawing of Rembrandt’s and explains to Mercè what the artist was doing. In a simple three minutes of film, he gives a master class in art–and one that any art student should attend to.

We learn more about the artist when a Nazi officer drives up to his mountain studio. Mercè–who at that point is hiding a wounded Resistance fighter–is naturally on alert. But the Nazi is there to discuss the biography he is writing on the artist. (He already has some 400 pages.) After the two discuss the book, the Nazi departs, telling Cros that he has been transferred to the Russian Front. We get the idea that he’ll never live long enough to finish his book.

The stories surrounding the making of The Artist and the Model are a lesson in creativity as well. Based loosely on the sculptor Aridste Maillol and his final model, Trueba began working on the script in 1990, intending to collaborate with his brother the sculptor Maximo. But Maximo’s young and sudden death, put Trueba off the project. It was not until, Rochefort, whom Trueba had already considered to play his sculptor, told him he was retiring that Trueba decided to go ahead with it.

It is undoubtedly, the high point of Trueba’s career so far, as it probably is also for Jean Rochefort. Indeed, like the sculptor that he plays, Rochefort’s finest performance–in a long and celebrated career–is here in this his final performance.

Certainly, there is much good art around. There is very little great art. The Artist and the Model falls into the second category.

Here is the trailer: