Adam Phillips begins his small book Darwin’s Worms with a story about the composer John Cage. Cage had attended a concert by a friend. In the program notes to the concert the friend had written that he hoped in some small way that his music helps to ease some of the suffering in our modern world. When Cage criticized this desire, the friend asked him if he didn’t think there was too much suffering in the world. “No,” replied Cage. “I think there is just the right amount.”

And so, Phillips writes, it is to remind us of and reconcile us to the fact that the amount of suffering in life is just the right amount that we turn to Darwin and Freud.

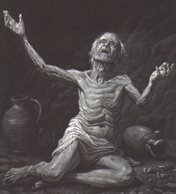

Darwin was very aware of the suffering in the natural world. Anticipating Freud on one level, he saw all organisms in a war for survival, thrust forward by an instinct to regenerate, adapting continually to a constantly changing environments. While the rest of his society were arguing, debating, proselytizing what it believed were the weightier implications of Darwin’s observations, Darwin studied the lowly earthworm, understanding its importance in the life of nature and, in turn, our own, (which he would argue is part of nature and not separate from). Flipping the usual symbolism on its head, removing the lowly worm from man’s symbolic last meal (“not where he eats, but where he is eaten”) and placing it at the continual meal that is life, Darwin points out that worms function in nature like plows, turning over soil and creating the soft and germinating loam that we take as the earth’s surface. As they struggle to survive (and “struggle” and “survival” are both key words in Darwin and Freud’s lexicon), worms leave behind shards of the past–that which they cannot digest–and form suitable soil for the plants that will provide for their future. Darwin states that:

“…it would be difficult to deny the probability that every particle of earth forming the bed from which the turf in old pasture land springs has passed through the intestines of worms.” That is a very large contribution to life on earth, powered simply by the worm’s instinctual drive to survive.

Later, Freud elaborated this drive, this instinct to survive and coupled it with its antithesis, the death instinct. At first, he termed them simply, the life instinct and the death instinct. Ultimately, he gave it the poetic designation of “Eros and Thanatos.” The life instinct is easy to understand. Man is driven to survive and to propagate. (“To be or not to be” becomes “to survive or not to be.”) The latter, however, the death instinct is a bit more difficult to get one’s head around. Freud believes that in the struggle to survive man also has a desire to cease that struggle–to stop the pain, if you will. However, the desire, says Freud, is also to be in control of that death. To make it part of one’s life story.

Later in the book, Phillips gives us passages from two separate biographies (“life stories”) of Freud. Both describe the same scene, Freud’s death (“death stories”). The scenes themselves are poignant, but what Phillips does with the passages is telling. In it, he shows Freud “controlling his death” the way that he thought all humans desired. In a way, it is a heroic portrait and an affirmation of Freud’s theories.

As Phillips concludes, in their work, both Freud and Darwin “ask us to believe in the permanence only of change and uncertainty… . to describe ourselves from nature’s point of view; but in the full knowledge that nature, by (their) definition, doesn’t have one.” In an work that analyzes mortality, death, and loss, Darwin’s Worms is a surprisingly upbeat and reassuring view of the world.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Freud famously said that there are no such things as coincidences. But today as I opened my computer to begin writing this post about Darwin and Freud, the homepage on my computer opened to this New York Times article revealing the discovery of the fossil of a nearly complete skeleton of what is the earliest primate known, changing scientists’ time-line for the appearance of primates on earth by 8 million years, and giving credence to the growing theory that primates emerged first in Asia rather than Africa.

Xijun Ni/Chinese Academy of Sciences An artist’s interpretation of a tiny primate that is thought to be the earliest known ancestor of nocturnal primates living today in Southeast Asia. from NYTimes 06/06/2013

How appropriate. Darwin would have been excited, for he saw great value in studying the simplest and earliest of life-forms, plankton, barnacles, and earthworms.