Creativity

Disney’s Folly, Snow White and Disneyland

I’ve been in Southern California for the past two weeks, and yesterday I spent 14 1/2 hours in Disneyland. With a very energetic seven-year old. And I’m completely exhausted.

But I am sure of this: no matter what people say about the Disneyfication of things, one has to admit that everything they do is efficient and entertaining. And often awe-inspiring.

When Walt Disney came to California, he focused on making short animated films, primarily the Mickey Mouse and the Silly Symphonies cartoons. But in 1934, he decided to produce the first feature-length animated feature…much to the dismay of his brother and business partner, Roy Disney, and the delight of the Hollywood critics who called Disney’s project “Disney’s Folly.”

For what sensible person, it was thought, would sit through a 90 minute cartoon?

Disney mortgaged his house, brought artists in to train his animators, emphasized a European look for the artwork ensign design, and spent close to $1.5 million in 1937 dollars to get his feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, completed.

If Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs hadn’t succeeded, most of us probably would never have heard of Walt Disney–except maybe for a few film students who might have studied his early cartoons. Instead the film’s success, both among the public and the industry, allowed Disney to capitalize on success after success until the Disney brand became what would have been unfathomable to Disney itself.

The story of the making of Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs is well documented: the switch from a rollicking tale about the dwarfs to the romantic love story it became, the metamorphosis of the Wicked Stepmother from a hare-brained slovenly witch to the sensuous, shapely queen that all boys of a certain age remember, the downplaying of the prince’s role in the plot–this is all a matter of history.

But no one would have cared about that history, if the film flopped.

On December 21, 1937, the film premiered at the Carthay Circle Theater. The premier, which was attended by all the Hollywood royalty—Judy Garland, Charlie Chaplin, Marlene Dietrich, Cary Grant, George Burns and many more were present—was an extraordinary success. Outside the Carthay Circle Theater, 30,000 fans who couldn’t get tickets waited. The NY Times led with the line, “Thank You, Mr. Disney” and Walt Disney and his Seven Dwarfs were on the cover of Time a week later. (Disney always saw the dwarfs as the centerpiece of his film.)

And the film made money. The numbers are staggering–within 15 months it had become the all time money making film ever–but more importantly Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs provided the seed money for what was to become the Disney Empire.

And so, as I trudged around Disneyland–visiting Radiator Springs and Ariel’s Undersea Adventure, as I watch Henson’s Muppets and a Broadway caliber Aladdin, as I witness technological and creative boundaries pushed and optimized–I realize what an awful lot has blossomed from Disney’s hunch that people, yes, would sit through ninety minutes of animation.

By the way…

Did you know that Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the first film to release a “soundtrack” album as a separate entity?

Quote of the Week #13: July 21, 2013

Quote of the week # 12: July 14, 2013

“After so many years, I’ve learned that being creative is a full-time job with its own daily patterns. That’s why writers, for example, like to establish routines for themselves. The most productive ones get started early in the morning, when the world is quiet, the phones aren’t ringing, and their minds are rested, alert, and not yet polluted by other people’s words. They might set a goal for themselves — write fifteen hundred words, or stay at their desk until noon — but the real secret is that they do this every day. In other words, they are disciplined. Over time, as the daily routines become second nature, discipline morphs into habit.

“It’s the same for any creative individual, whether it’s a painter finding his way each morning to the easel, or a medical researcher returning daily to the laboratory. The routine is as much a part of the creative process as the lightning bolt of inspiration, maybe more. And this routine is available to everyone.

“Creativity is a habit, and the best creativity is a result of good work habits.”

Twyla Tharp, The Creative Habit

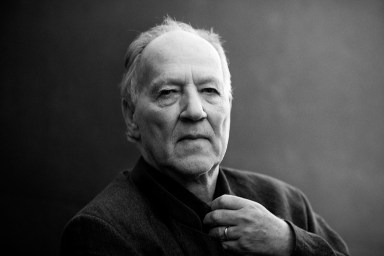

Werner Herzog, Northern Liberties and my neighbors’ art

So it is August last year and I’m with a group of people at a street fair on 2nd Street and we’re standing watching the children attempting to throw over-sized basketballs into undersized hoops. All of a sudden, the barker takes away one of the balls and points it to me. “Let’s give Werner Herzog a try,” he says.

Now, I’ve have been compared to a lot of people in my time–both as insults and as compliments–but I had never been compared to Werner Herzog before. We all had a laugh and promptly forgot about it…until this past Tuesday, that is.

Anyway, I was walking down 3rd Street to my local when I passed the abandoned Ortlieb’s brewery at 3rd and Poplar. It is a derelict building with a lot of character but in really great disrepair, and nobody yet has taken the risk to convert it to anything. Anyway, I was surprised to see, yet again, a reference to the German film director: Brand new graffiti spray-painted on the brewery wall.

What is the fascination with Herzog in my little neighborhood? I photographed it immediately.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Philadelphia is very proud of its wall art–murals that dot the city–and visitors can now take one of several bus tours visiting the more spectacular ones. But in my neighborhood of Northern Liberties, the wall art is not necessarily all that official–but it is more than impressive. And so on Wednesday, I took my own little tour of just a one block by two block area, snapping whatever pieces I saw.

A half-block north of the Ortleib’s brewery is Liberty Lands Park. Its southern wall is Kaplan’s Bakery and the air is filled with the aroma of baking bread–bread that makes its way to many of the restaurants throughout the city. The wall is filled with a three-dimensional mural of birds and bees and a map of the land as it once was.

At the northeast corner of the park, where Bodine crosses Widley, there is a house where the owners have painted a interesting tale on their wall. The famous tortoise (looking a bit startled) is crossing the finish tape, held up by a pigeon and an owl. The hare is nowhere in the picture. Hah!

Immediately across the street, ten meters from the tortoise, a neighbor has painted his garden fence in lush roses.

A block away in one direction, there is a coffee shop…

… and a block away in the other direction is GreenSaw, an environmentally-conscious design, architectural, construction firm that makes furniture, does remodeling, and sells DIY materials and supplies—all earth friendly and green. I guess that pleases the orangutan on the wall next to them:

Movie Review: Hannah Arendt dir. by Margarethe von Trotta

The philosopher, political theorist and writer, Hannah Arendt has received a thoughtful and deserving biopic from director Margarethe von Trotta, in her eponymous film, Hannah Arendt. The film’s intelligence reflects the life of the mind that Arendt lived–and an honest and hard intelligence at that. Concentrating on the period when Arendt covered the Adolph Eichmann trials for New Yorker magazine–and the fury that it unleashed– it shows Arendt resolute in her thinking, uncolored by prejudice or sympathies.

Her coverage of the Eichmann trial ended with these words, this pronouncement:

Just as you [Eichmann] supported and carried out a policy of not wanting to share the earth with the Jewish people and the people of a number of other nations—as though you and your superiors had any right to determine who should and who should not inhabit the world—we find that no one, that is, no member of the human race, can be expected to want to share the earth with you. This is the reason, and the only reason, you must hang.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Arendt’s biography is well know. Born into a secular Jewish family, she studied under Martin Heidegger with whom she reportedly had a long affair. Her dissertation was on Love and Saint Augustine, but after its completion she was forbidden to teach in German universities because of being Jewish. She left Germany for France, but while there she was sent to the Grus detention camp, from which she escaped after only a few weeks. In 1941, Arendt, her husband Heinrich Blücher, and her mother escaped to the United States.

From there she embarked on an academic career that saw her teaching at many of the U.S.’s most prestigious universities (she was the first female lecturer at Princeton University) and publishing some of the most influential works on political theory of the time.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

But the film, concerns a small time period in her life–but one for which many people still hold a grudge. The film begins darkly with the Mosada snatching Eichmann off a dark road in Argentina. Back in New York City, Arendt (Barbara Sukowa) and the American novelist, Mary McCarthy (Janet McTeer) are sipping wine and gossipping about the infidelities of McCarthy’s suitors. Even genius can be mundane–perhaps a subtle reference to Arendt’s conclusions from the trial. When news of Eichmann’s arrest–and trial in Israel–is announced, Arendt writes to William Shawn (Nicholas Woodeson) at the New Yorker, asking if she might cover the trial for the magazine. Shawn is excited; his assistant, Francis Wells (Megan Gay,) less so.

But the film, concerns a small time period in her life–but one for which many people still hold a grudge. The film begins darkly with the Mosada snatching Eichmann off a dark road in Argentina. Back in New York City, Arendt (Barbara Sukowa) and the American novelist, Mary McCarthy (Janet McTeer) are sipping wine and gossipping about the infidelities of McCarthy’s suitors. Even genius can be mundane–perhaps a subtle reference to Arendt’s conclusions from the trial. When news of Eichmann’s arrest–and trial in Israel–is announced, Arendt writes to William Shawn (Nicholas Woodeson) at the New Yorker, asking if she might cover the trial for the magazine. Shawn is excited; his assistant, Francis Wells (Megan Gay,) less so.

Of course, the trial–and Arendt’s commission to follow it–is fascinating and controversial and we listen in on Arendt and her husband and their circle of friends as they debate and argue and opine. Aside from Mary McCarthy and the head of the German department at the New School where Arendt is teaching, the guests at Arendt’s apartment are all friends from Europe, German-Jews who have escaped the Shoah/Holocaust. Listening to their different conversations is fascinating and electrifying. This is a movie about “thinking.”

In Israel, Arendt meets with old friends, friends who remember her argumentative spirit, and stays with the Zionist, Kurt Blumenfeld. From the outset, one sees that Arendt is not thinking along the same lines as the masses following the trial.

“Under conditions of tyranny it is much easier to act than to think.”

Hannah Arendt

At the trial, there is a telling moment, when Arendt watches Eichmann in his glass cage sniffling, rubbing his nose and dealing with a cold. It is then, a least in the film, that she comes to understand that this monster is not a MONSTER. She sees him as simply a mediocre human being who did not think. It is from here that she coins the idea of the “banality of evil.”

Upon returning home–with files and files of the trial’s transcripts–her article for the New Yorker is slow in coming. Her husband has a stroke, and the enormity of what she has to say needs to be perfect.

When it is finally published, the angry reaction is more than great. The critic Irving Howe called it a “civil war” among New York intellectuals. (Just last week, the word “shitstorm” was added to the German dictionary, the Duden, partly due to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s use of the word to describe the public outcry she faced over the Eurozone’s finacial crisis. It is an apt term for what occurred upon publication of Arendt’s coverage.)

It is this extraordinary anger towards Arendt–and her staunch defense–that makes up the final moments of the film. In the closing moments, Arendt speaks to a packed auditorium of students (and a few administrators). She has just been asked to resign, which she refuses to do. These are her closing words:

“This inability to think created the possibility for many ordinary men to commit evil deeds on a gigantic scale, the like of which had never been seen before. The manifestation of the wind of thought is not knowledge but the ability to tell right from wrong, beautiful from ugly. And I hope that thinking gives people the strength to prevent catastrophes in these rare moments when the chips are down.”

This is, more than anything else, a film about thinking.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

The extraordinary anger shown in the film is still felt by many today and, in fact, seems to have colored some of the reviews that I have read and heard. Some of these reviewers seem to be reviewing the life and work of Arendt and not the film of Margarethe von Trotta, for von Trotta’s film is a unique, masterpiece. It is more than a biography of a controversial thinker…it is a portrait of thought itself. Arendt attempts to define “evil”–certainly an apt exercise at the time. She defines it–to her friends, to her classes, to her colleagues, and to herself–and finds that it is not “radical” as she once had posited. It is merely ordinary. Goodness, she sees, is what has grandeur.

The film, Hannah Arendt, is well worth seeking out. It is thoughtful, provoking, controversial, and, at times, even funny. You can’t ask for much more for the price of a movie ticket. As always, here’s a trailer:

Dylan’s rhythms and the 13-year old poet

So, out of the blue on Saturday morning I receive a poem by a young boy, Domenic Feola, thirteen years old. I don’t know him, never taught him, probably never will. He is a suburban kid who runs cross-country at one of the city parks. But his ear is impeccable and his language is crisp. And the rhythm of his poem is infectious (until the last couplet where in trying to sum up his feelings he loses is footing) .

So, out of the blue on Saturday morning I receive a poem by a young boy, Domenic Feola, thirteen years old. I don’t know him, never taught him, probably never will. He is a suburban kid who runs cross-country at one of the city parks. But his ear is impeccable and his language is crisp. And the rhythm of his poem is infectious (until the last couplet where in trying to sum up his feelings he loses is footing) .

The City

by Domenic Feola

Bright lights, fast trains

Cold nights, heavy rains

Dirty air, bus fare

Pigeons flying everywhere

Crowded streets, traffic jams

Music beats, grand slams

Bugs fly, kids cry

No stars in the night sky

Noisy bars, littered trash

Big cars, no cash

Garbage smells, huge hotels

In the shadows, spiders dwell

Scary strangers, taxi cabs

Hidden dangers, science labs

Museums of art, cherry tart

Broken beat up shopping carts

If you say I’m biased, I would agree

I think the suburbs are more for me.

Pretty sophisticated for a thirteen-year-old boy. Or for anyone, for that matter. Great imagery, great confidence and impressive rhythm. If I could, I would talk to him about the rhythm. That is the strength of the poem–but there are a few times where it needs to be tightened, where some minor tweaking would make it even better. But it is impressive nevertheless.

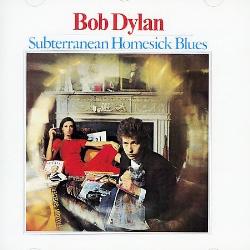

In fact when I first read the poem I could hear Dylan–specifically “Subterranean Homesick Blues” –in the rhythm. Here’s the second verse from Dylan’s song:

Maggie comes fleet foot

Face full of black soot

Talkin’ that the heat put

Plants in the bed but

The phone’s tapped anyway

Maggie says that many say

They must bust in early May

Orders from the DA

Look out kid

Don’t matter what you did

Walk on your tip toes

Don’t try, ‘No Doz’

Better stay away from those

That carry around a fire hose

Keep a clean nose

Watch the plain clothes

You don’t need a weather man

To know which way the wind blows.

from “Subterranean Homesick Blues”

The short 5 and 6 syllable lines are similar. The grammatical “packages” the same.

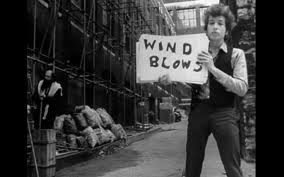

Now, I read someone say that this Dylan song was one of the first rap songs. But that’s not true, it’s utter nonsense. Dylan was influenced by “talking blues,” Chuck Berry’s rock-and-roll, and the Beats like Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Ferlinghetti. (Notice in the iconic picture at the top, Alan Ginsberg talking to folksinger Bob Neuwirth on the left side of the photo.)

On the other hand, Dominic Feloa (who probably doesn’t know who Bob Dylan is) more than likely has been influenced by rap and hip-hop. It is all around him, in the music he listens to, the advertisements he is bombarded with, the zeitgeist of the culture. Yet his rhythms are a bit different. It might be that his non-urban background (and his youth) gives his rap rhythms a subtle difference, a blunter edge. But they are working.

So, cheers to Dominic Feloa. Keep writing. Show your work to your teachers. Find someone to work with, to work against. Write–revise–and write again. Send your work out. Expect rejection. Work harder. Good luck to you. Thanks for letting me read your poem.

And, of course, I couldn’t leave without sharing a video, a promotion for the 1965 Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back, a promotion that did have an enormous influence on what was to become “music videos.” This was the original…it has been copied/parodied countless times:

Mother’s advice: “if you have nothing nice to say…”

I went to the movies on Monday afternoon to see a film that I had been wanting to see for the past month or so. But I left the theater greatly disappointed. And as I walked up 3rd street, I thought to myself, I am not even going to write about this one.

And I think I am right.

I am not a critic–of film, books or music–I simply enjoy these things. And I enjoy writing about them and sharing my enthusiasms about them. But, I don’t feel comfortable bad-mouthing the ones I don’t like. On Wednesday I posted a piece about a book I didn’t like and I feel more than a little discomforted about it.

In this vast “blogosphere” where everyone so easily can send out his or her opinions, I want to rein myself in. Of course, BAD ART exists–there are books that are dreadful, movies that are deadening, music that irks me, but they will find their own levels of acceptance, they will find their own audiences (or not) without my weighing in.

And besides, I don’t have the time to waste on negativity.

After all, all creativity is risk…risk of missing the mark, of being misunderstood, of being ripped apart. But one has to put it out there and let it find its own life. (As Woody Allen says, “Eighty percent of success is just showing up.”)

So, I’m sitting in a shop having a coffee after the movie and am asked what I thought. “I didn’t like it,” I say, and I give my reasons, listen to counter-positions, discuss the pluses and minuses. This is good, this is what Art should engender–conversation, dialogue, thought, and, yes, even judgment.

So, I’m sitting in a shop having a coffee after the movie and am asked what I thought. “I didn’t like it,” I say, and I give my reasons, listen to counter-positions, discuss the pluses and minuses. This is good, this is what Art should engender–conversation, dialogue, thought, and, yes, even judgment.

But is there really a need for me to blast it on the internet? I’m not so sure, but I don’t think so.

Don’t get me wrong; I will point out inconsistencies in the things that I like, choices and perspectives I disagree with, differences and surprises that throw me, things I see as flaws or would have wished the artist had done differently.

But with things that I don’t like…? Well, as my mother would say, “if I have NOTHING nice to say, I’m not going to say it.”

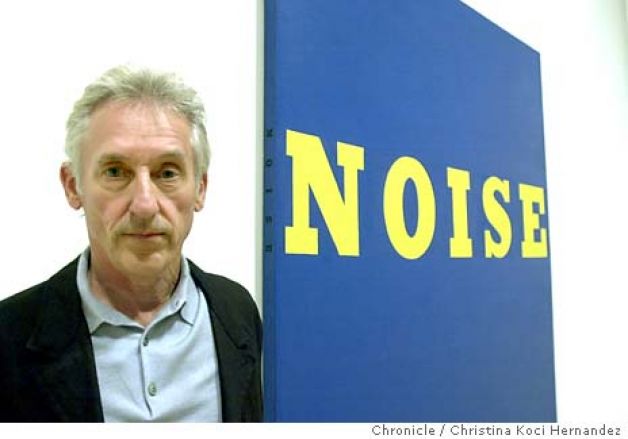

Book Review: Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles by Alexandra Schwartz–“learning what I do not know”

I received a book about six months ago as a gift: Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles by Alexandra Schwartz. At first I thought it was a travel guide, for I was headed to L.A. a few weeks later and I just assumed it was a book detailing the more out-of-the-way spaces to see. Except that it was much too nice a book for a mere travel guide: small and compact with fine paper, hard-board covers and peppered with illustrations. I put it aside to read it at another time. (I have since spilled an entire cup of coffee on it in a place where food and drink was forbidden. Deserved bad karma!)

I received a book about six months ago as a gift: Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles by Alexandra Schwartz. At first I thought it was a travel guide, for I was headed to L.A. a few weeks later and I just assumed it was a book detailing the more out-of-the-way spaces to see. Except that it was much too nice a book for a mere travel guide: small and compact with fine paper, hard-board covers and peppered with illustrations. I put it aside to read it at another time. (I have since spilled an entire cup of coffee on it in a place where food and drink was forbidden. Deserved bad karma!)

Anyway, boy was I wrong about the travel guide…and ignorant of an artist and a whole school of painting.

I had been completely unaware of Ed Ruscha–and of Los Angeles art. And I was not alone. In fact, much of the book’s focus is how the Los Angeles’ school of Pop Art has always played the poor sister to New York’s more celebrated school. And yet, unlike many cultural movements in which a western migration can honestly be traced, Pop Art in America seems not to have originated on the East Coast and worked its way across to California. Apparently, according to Schwartz, Pop Art seems to have arisen simultaneously in various parts of the country, reacting to and inspired by the same cultural influences.

In 1962, the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles mounted an exhibit entitled “The New Painting of Common Objects.” The British critic, Lawrence Alloway–the man who coined the term “Pop Art”–cites it as being the first exhibit of American Pop Art. In fact, the gallery–and its curator Walter Hopps–was the first to exhibit Warhol’s iconic Campbell Soup Can–arguably, the defining image of Pop Art–two months before it was shown in New York. The list of artists at “The New Painting of Common Objects” exhibit included Lichtenstein, Dine and Warhol from the East Coast, Phillip Hefferton and Robert Dowd from the Mid-West, and Edward Ruscha, Joseph Goode and Wayne Thiebaud from the West. It was the nation’s introduction to Pop and a major stroke for the establishment of Pop Art in the country. This, and the fact that the respected art magazine ArtForum had its offices above the Ferus Gallery where the show was staged, would seem enough to move the spotlight onto the Los Angeles’ art world, but it wasn’t. But New York is much too big a player. (Ultimately ArtForum moved there, as well.)

Ruscha hit the L.A. scene young, having hitchhiked in from Oklahoma at the age of nineteen. He enrolled in what is now the California Institute of Arts and afterwards worked–like his contemporary Warhol–in advertising. And like Warhol, his collages, his word-art, the signage and everyday objects, and his photographs greatly showed the influenced that advertising had on him.

Ruscha’s work is vibrant and fun, enigmatic and engaging, uncluttered and beguiling. Besides his artwork, he has created numerous books and films, and often collaborates with artists, writers and publishing houses on lay-out and cover designs. He still works and lives in Southern California.

To be truthful, the book, Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles itself, however is a bit heavy going and academic at times. (It was published by MIT and was originally Schwartz’s doctoral dissertation). But nevertheless, it is a wonderful introduction to Ruscha’s art.

At least for me, for whom he was a completely new name. And one that I am enjoying discovering.

“Always learning, even if it’s simply that I do not know.”

Yes, Yes, Yes: Affirmation ala Molly Bloom

yes I said yes I will Yes.

Last Sunday was Bloomsday, the international celebration of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses.

Dublin had its usual extravaganza with crowds retracing Leopold Bloom’s wanderings and with women’s hats that rivaled those worn at major horse races (remember to bet it all on “throwaway.”) In New York, the complete novel was read outside writer Colum McCann’s tavern, aptly named Ulysses. And at Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum and Library, (where Joyce’s manuscript is housed) there was, beside the usual full reading, an unusual installation.

The artist, Jessica Deane Rosner, wrote out the entire text of the novel on 310 yellow, rubber, dish gloves and suspended them from the gallery ceiling in a very Joycean spiral. Rosner stated that it was Joyce who showed us that the things of everyday life–including the muck and the un-pretty–are the very essence of and inspiration for Art.

And so she used the mundane kitchen gloves to carry Joyce’s text–a text replete with the beauty of life’s mundane grime and natural effluences.

But that’s not what I want to talk about today. …

I want to talk about the last seven words of the novel, the strong affirmation that ended Molly Bloom’s long nighttime reverie in the early hours of June 17, 1904.

It is this affirmation, the “yes I said yes I will Yes” that makes Ulysses so important. For, if ever there was a modern Everyman, it is her husband, Leopold Bloom. Leopold the ridiculous, the schlump, the man she has cuckolded just hours before. Leopold the grieving, the masturbatory, the lecherous, the neighborly, the isolated, the humane, the persecuted. And to him–and he is each of us– Molly proclaims a resounding Yes!

And we all need to do more of the same. To say “Yes.”

I have a good friend, Ken Campbell, who served thirteen long months in Vietnam before becoming one of the leading figures in the Vietnam Vets Against the War movement. This fall the two of us went together to see Samuel Beckett’s Endgame. I wallowed in the existential bleakness; he did not. He enjoyed the company. He had spent too long in Vietnam, wondering every night if he was going to live another day, and today he has no time for Beckett’s desperate vision.

He sides much more with Molly Bloom’s “Yes”!

So here’s to saying “yes.” Saying “yes” to all the myriad things and people that life places in front of us: like the noodle shop at 56th and 6th in NYC… the children’s fountain on the Ben Franklin Parkway…the surprise of 310 yellow rubber gloves hanging from an elegant ceiling.