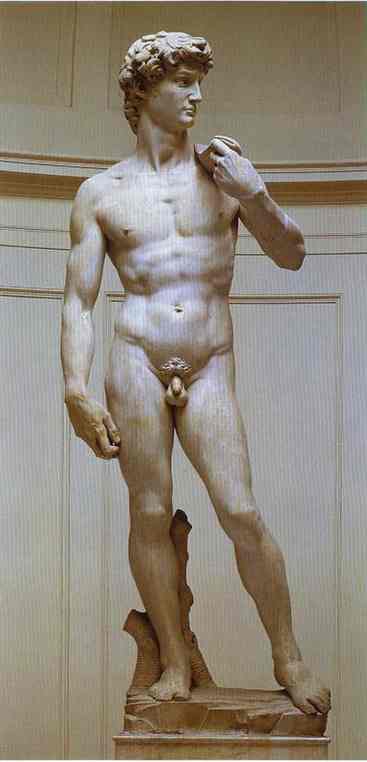

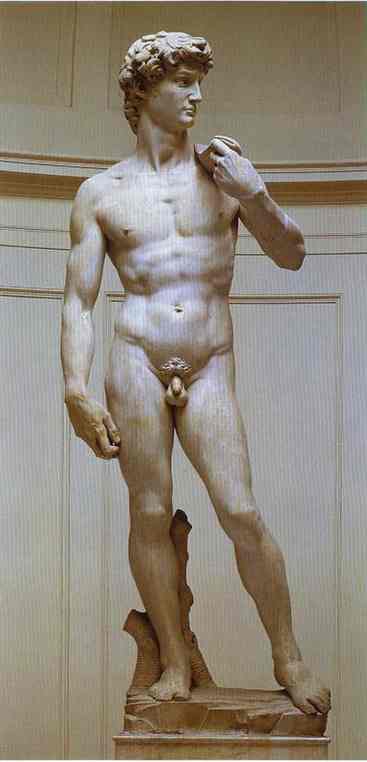

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in Reason!

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in Reason!

how infinite in faculties! in form and moving how

express and admirable! in action how like an Angel!

in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world,

the paragon of animals. and yet to me, what is

this quintessence of dust?

Hamlet, Act II, Scene ii

And it’s true. The human body is an extraordinary piece of work, a marvelous machine inside and out. Just look at the accomplishments of this summer’s Olympic athletes–the speed, the agility, the grace, the strength.

And while most of us do not have–and never will– the bodies of an Olympian, we do have something very much in common: our bodies will ultimately rebel against all of us.

I have spent the recent past with bodies that are failing to various degrees. My mother’s body–stricken with Parkinson’s disease for the past fifteen years–was continually at war with itself, the brain sending damaged impulses to the rest of her body. Uncontrollable tremors, catatonic staring, personality changes, rapid mood swing, fevers, chills, labored breathing–these were the mutinies that the disease in her body raised against its very host. And in the end, the disease won.

On a much lesser scale, my own body is now wearing down. Aches and pains are common enough, but then my knee screamed out, began to fail. So a surgeon goes in–part of the extra-ordinariness of that piece of work that is man!–and some things are cut out, scraped out and removed, damaged pieces all due to the passage of time, to the ordinary wear and tear.

And then, again, my body foments a small uprising against the surgery itself. There are some complications after the surgery, some minor concerns with my leg.

And so for the first time in two weeks, I read a book. A marvelous book and one that I enjoyed immensely.

Paul Auster’s Winter Journal is a beautiful piece of writing–beautiful in the way that all of Paul Auster’s writing is beautiful: clear, intelligent, imaginative and clever.

The premise of the book–is it a novel, a memoir, a journal? the genres are often cloudy in Auster’s writing–is that on a particularly day, one month exactly to his 64th birthday, a writer sits down and writes a journal addressing his aging body.

The book is told in the second person–a technique I don’t particularly like but which here provides a close intimacy with the physical, emotional, and psychological body he is addressing. And yet there is a myriad of voices–a chorus of voices made up of the writer’s body at the various moments in his life

Throughout, the writer addresses his body in certain phases of his life. He examines the physical scars that have added up over an active boyhood: when he is five a playmate hits him in the head with a metal rake; when he is three-and-a-half he slides into a protruding nail and has much of his face ripped apart; as a ten year old baseball player he is smacked into by another player as he looks up to catch a ball and splits his head open.

But the scars are not only physical. There is the death of his mother, the panic attacks, the cessation of driving after he and his family survive a near fatal car accident.

But the scars are not only physical. There is the death of his mother, the panic attacks, the cessation of driving after he and his family survive a near fatal car accident.

He remembers when as a little boy in a tub the wondrous surprise of an erection and as a grown man the various women he has loved both in late adolescence and in manhood. He recounts the unshakeable love that he and his wife share. He remembers the exhaustion of producing a film in Dublin and the clarifying epiphany that metamorphosed him into a serious writer. There are memories of women he has loved and men he admires. Of situations, in Arles, in Dublin, in Brooklyn where he learned–and retained–a certain self-knowledge about himself.

And overall, it is the pleasure he remembers his body enjoying, much more than the pain. When, at the age of five, he was hit by the rake, he was lying on the ground examining an ant-hill. And it is his boyhood fascination with those ants that he remembers more than the delivered blow which literally raked his head. When he is cracked in the head by the fellow teammate, it is the joy of following an arcing baseball, of angling to bring it into one’s mitt that he remembers more than the bloodying crash.

And now at this juncture of his life, it is always the pleasure not the pain that his aging body (and mind) remembers most clearly.

Winter Journal is –perhaps surprisingly–an uplifting book. A man, growing old but not nearing what he calls “advanced old age,” seems somewhat content with the life that he has lived so far. There is still a boy’s joy with a winter snowstorm, a lover’s appreciation of his longstanding wife, a satisfaction with the things he has accomplished–and a recognition of the many that never made it to the age he is now approaching.

In many ways, Winter Journal is a fine, fine book…a fine, fine way of looking at a life.