A few years ago, in an attempt to be a cutting-edge, high-tech institution, the powers-that-be decided that the school I teach in didn’t need a library. The library is superfluous, they claimed. Students have all the information they need on their phones in their hands. (As if information was all that students need.) And so, quickly, the library was gutted, the librarian dismissed, and the books were donated, destroyed, or “disappeared.” From its ashes rose a Maker-Space and a Learning Commons. (If you are not currently involved in modern education, don’t ask.)

“The Library Where the Sidewalk Ends” on Valentine’s Day

A few colleagues and I couldn’t imagine a school without a library, so we built our own. A “little library” it was, and ones like it appear in neighborhoods, towns and cities throughout the U.S. (I once was at a ribbon-cutting ceremony for such a library on the porch of a bar in Key West, although it was much more of a Key West celebration than a library opening.)

Anyway, the library thrived with people taking and leaving a variety of books, CDs, and even art works.

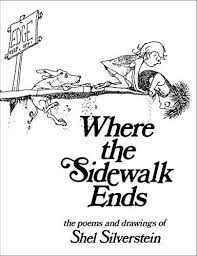

The library itself was located in an odd place in the middle of campus. There was a cement sidewalk that jutted into a swatch of grass and then just ended. When I would announce new additions to the library, I would refer to it as “the library WHERE THE SIDEWALK ENDS.”

And every student and every adult knew what I was referring to: the delightful first collection of poems by Shel Silverstein that every student had loved as a child and every adult of a certain age remembered reading to his or her own. The poems in Where the Sidewalk Ends are silly, irreverent, charming, and knowing. It’s the silly irreverence that children most love: as if the adult Silverstein—unlike other adults in their world— was clued into the fears, the joys, the silliness, the incomprehension, the absurdity with which they view the world.

And every student and every adult knew what I was referring to: the delightful first collection of poems by Shel Silverstein that every student had loved as a child and every adult of a certain age remembered reading to his or her own. The poems in Where the Sidewalk Ends are silly, irreverent, charming, and knowing. It’s the silly irreverence that children most love: as if the adult Silverstein—unlike other adults in their world— was clued into the fears, the joys, the silliness, the incomprehension, the absurdity with which they view the world.

Yet, Silverstein was more than a children’s poet. He began as a cartoonist, and a successful one. It was his cartoons that prompted his publisher to suggest a book of poems. He was also a playwright–David Mamet called him his best friend–with over 100 one-act plays under his belt.

And he was a prolific songwriter. He had a number of hits with what could be called novelty

Shel Silverstein

songs: “On the Cover of the Rolling Stone,” “Sylvia’s Mother,” “A Boy Named Sue,” and the “Unicorn” song ( you know, “green alligators and long necked geese… .”) But he also had a solid stable of songs recorded by a slew of people: Dr. Hook and his Medicine Show, Loretta Lynn, Bobby Bare, Belinda Carlisle, Waylon Jennings, Emmylou Harris, Marianne Faithful, Johnny Cash among others. I remember the first Judy Collins’ album I ever bought featured a rousing protest song called “Hey Nelly Nelly.” I didn’t recognize the name at the time, but it was written by someone named Shel Silverstein.

And so it comes to a song I have recently rediscovered. I was buying tickets to see Todd Snider in concert and was looking for the one Todd Snider album I own. I couldn’t find it. So instead I pulled out a Robert Earl Keen album West Textures which features a charming Shel Silverstein song, “Jennifer Johnson and Me.” (Snider mentions a Robert Earl Keen song in one of his own songs which is what originally had driven me to this album.)

Anyway, the song tells the story of a man who finds in an old suit jacket pocket a black-and-white photo (‘three for a quarter”) from an arcade photo booth. The picture is of him and an old girlfriend, Jennifer Johnson. The singer is well into adulthood now, and the photo is of him when he was in late adolescence, sitting with Jennifer Johnson.There is a sweet nostalgia in his memories of their innocence, their hope, and the belief in “forever.”

It’s a sweet song, and I opened up with it on Saturday. I think I will keep it in my set list. Here’s the tune, by Robert Earl Keen:

actual death of Roland Barthes, who was killed by a laundry van, is determined to be NOT AN ACCIDENT and the suspects include everyone from Mitterrand to Foucault, from Umberto Eco to Noam Chomsky. It is a bold and nervy novel that merges the modern detective story with outrageous flights into semiotics.

actual death of Roland Barthes, who was killed by a laundry van, is determined to be NOT AN ACCIDENT and the suspects include everyone from Mitterrand to Foucault, from Umberto Eco to Noam Chomsky. It is a bold and nervy novel that merges the modern detective story with outrageous flights into semiotics. side and compete with each other for the boy’s favor. Meanwhile, the grieving president continues to visit. It is an extraordinary, emotional and satisfying read.

side and compete with each other for the boy’s favor. Meanwhile, the grieving president continues to visit. It is an extraordinary, emotional and satisfying read. manipulation, war, the classical musical world, gaming, and academic integrity, Hill seems to have bitten off far too much. But he brings it all together to serve up one extraordinary and satisfying novel.

manipulation, war, the classical musical world, gaming, and academic integrity, Hill seems to have bitten off far too much. But he brings it all together to serve up one extraordinary and satisfying novel. Times ended up to be much, much more–a wonderful peek into a Parisian street and neighborhood that has resisted progress and gentrification and tourism, and which continues in much of its uniqueness and tradition.

Times ended up to be much, much more–a wonderful peek into a Parisian street and neighborhood that has resisted progress and gentrification and tourism, and which continues in much of its uniqueness and tradition. –particularly writers and artists and herself– walking in world cities, though with a concentration in Paris. I am grateful for its introducing me to the marvelous artist Sophia Calle, whose one amusing art work involved walking around Venice while following a strange man. (It also introduced me to Georges Sand, of whom I knew very little. Two of her enormous novels sit next to my bed, waiting for 2018.)

–particularly writers and artists and herself– walking in world cities, though with a concentration in Paris. I am grateful for its introducing me to the marvelous artist Sophia Calle, whose one amusing art work involved walking around Venice while following a strange man. (It also introduced me to Georges Sand, of whom I knew very little. Two of her enormous novels sit next to my bed, waiting for 2018.) Rebecca Solnit, whose “invisible cities” books have given me much enjoyment in the past. This year I turned to her Field Guide to Getting Lost, a wonderful meditation on the usefulness and growth achieved in being lost somewhere. Like all of Solnit’s work, the main thesis is simply a jumping off point for all sorts of insights and reflections.

Rebecca Solnit, whose “invisible cities” books have given me much enjoyment in the past. This year I turned to her Field Guide to Getting Lost, a wonderful meditation on the usefulness and growth achieved in being lost somewhere. Like all of Solnit’s work, the main thesis is simply a jumping off point for all sorts of insights and reflections.

collection of seven essays, mostly first-published on the web-site TomDispatch, that focus on the reality and the dangers (and some of the absurdity) found in the patriarchy of modern civilization, dangers that include murder, violence, and rape, as well as condescension and subordination.

collection of seven essays, mostly first-published on the web-site TomDispatch, that focus on the reality and the dangers (and some of the absurdity) found in the patriarchy of modern civilization, dangers that include murder, violence, and rape, as well as condescension and subordination.