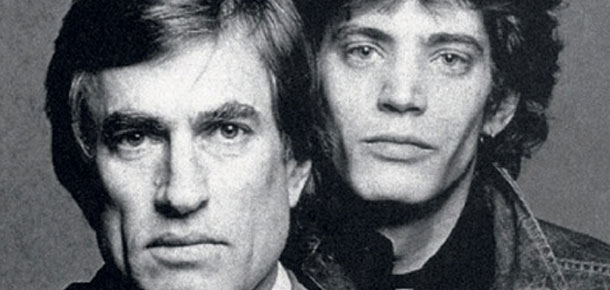

The summer of 2013 began with the release of Baz Luhrman’s The Great Gatsby, and everyone was in a race to compare it with the Robert Redford version from the 1970s. To be truthful, I never cared for Redford as Gatsby, but thought the rest of the cast was spot on. The opposite goes with Baz Luhrman’s film, in which I prefer DiCaprio’s Gatsby to the rest of the cast.

But we forgot about all that–and rather quickly– before the summer actually began, and now we have a new version of another “classic” work of literature: Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Joss Whedon, which must undoubtedly be compared with the Kenneth Branagh version of 1993.

The story behind Whedon’s project is fun. It was something that he had long wanted to do, and finally his wife suggested that instead of going away on vacation for their 20th-anniversary, they make the film. And they did…entirely in their gorgeous home. Whedon gathered many of the actors who had played in his previous productions, and the first that Hollywood knew about the film was when they announced that photography had been completed. They had wrapped things up in 12 days.

Whedon chose to film in black-and-white which gives the film a stylish patina. And yet, I found it drained some of the emotion from the story. Benedick (Alexis Denisof) and Beatrice (Amy Acker) are likeable enough, and quite funny at times, but they shine mostly when they are apart…there are few sparks when they are together. Invariably, one has to compare them to Kenneth Brannagh and Emma Thompson–whose fire (both on film and personally) was palpable. And the golden sunlight of Tuscany, the shimmering palette of the entire film, gives Brannagh’s version a much richer patina.

Whedon’s actors all handle the dialog well and naturally, and after a few minutes you might even forget you are listening to Shakespearean English.

In both films, the constabulary are very good–verbal slapstick and mental banana skins. Nathan Fillon’s doltish Dogberry in Whedon’s film is every bit as memorable–and laugh-inducing– as Michael Keaton’s dimwitted portrayal in the 1993 version.

And the performance of Clark Gregg, as Leonato, Hero’s father is likeable and believeable. Much of the audience will quickly forget that he is Agent Phil Coulson of the Avenger’s franchise (also by Joss Whedon).

However, there are a few choices that Whedon made that I am not so sure about. The character of Conrade, for example, which was played by Richard Clifford in the Brannagh version has now been changed to a female role, played by Riki Lindhome. This in itself is usually not a problem. For instance, in Michael Almareyda’s Hamlet (starring Ethan Hawke), Marcello was changed to Marcella and played by Paula Malcomson. But nothing is changed, the part is minor, and her lines are few. In Whedon’s Much Ado…, the Conrade character is quite sexy and there is even a bit of titillating bed-play between her and Don John (Sean Maher), although the words of the play would not lead us to think so.

There is also a scene that is not in the play–during the opening credits–where Benedick sneaks out of Beatrice’s bed in the early morn. Beatrice lies there feigning sleep, but slyly opening her eyes as he dresses and leaves. We are left with the vision of her wide awake in bed, with eyes that speak of her aloneness. If this scene is supposed to prepare us for the friction between the two when the play proper begins, it fails.

Whedon shares writing credits with William Shakespeare, and, to be honest, he does a very admirable job. He has cut judiciously, and the only time he has changed the language was in Act 2 where he excised an anti-Semitic remark and changed it to a statement about love’s foolishness. The new line flows seamlessly into the original.

In all, I prefer the Brannagh version, but that is not to dismiss Whedon’s, which also I like very much. Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing is inventive and imaginative and aimed at a whole new audience. The filming is crisp, fresh, and confidant–and quite stylish. Whedon has successfully taken Shakespeare out of the classroom and made it very hip, without destroying the story at all. It is certainly worth viewing…and more than once. If this was his gift for his 20th anniversary, I hope he tackles another Shakespeare title before his 40th anniversary comes around.

Here is the very elegant and engaging trailer: