Errol Flynn as Robin Hood (1938)

Guy Williams as Zorro (1957-1962)

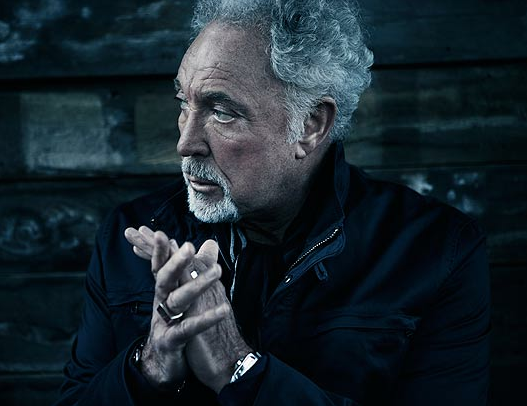

As a child I had two heroes–characters whom I would pretend to be, jumping off walls, running in alleys and woods, with friends or by myself. The one was Robin Hood. The other was Zorro. These were my heroes–and I’m sure for a variety of reasons. They both were rebels, outsiders fighting against established tyranny. (The evil Prince John in the former case, Spanish rule in the latter.) Robin Hood fought for the little people (the put-upon Saxons) as did Zorro (the colonized Californians.)

Both were dashing swashbucklers and always more cunning and cleverer than their enemies. They were both perfect role models for a young boy, for in addition to their skill with swords and bows and horses, in addition to their noble goals and pure hearts, they were gentlemen. And for some reason that appealed to me. (Probably for the same reason why I believe God should sound like Cary Grant in all portrayals!)

As I grew and my reading advanced, I found other such characters that appealed to me: The Three Musketeers, The Scarlet Pimpernel, even Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities. Unwittingly, I was drawn to those characters who punctured the established hypocrisy and tyranny and who stood up for the little guy, the oppressed, the wronged.

Albert Finney as Tom Jones (1963)

And then I discovered Tom Jones. His skills were nowhere near as impressive as the others–although he was a great sportsman, a horseman, and a lover of life–but his charm and his concern for the weak and put-upon were similar. And he was the ultimate outsider–he was a bastard, found lying in the bed of the benevolent Squire Allworthy. Tom’s enemies were the hypocritical upper class who resented his being taken in by the squire, and who, in a way, both condemned and envied his life-loving ways. He was easy to root for. Certainly, he had his faults, but even these faults could be explained away. And in the end, he one-upped the toffs who had persecuted him–affirming life over priggishness.

So where is this all taken me? To a “hero” I can’t abide.

A friend of mine, a writer and comic in Brooklyn, had often asked me if I had ever read any of George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman novels. I hadn’t, but promised I’d look into them. But I never got around to it. Finally, as a gift last Christmas, he bought me the first novel, Flashman.

Book Cover of Flashman by George MacDonald Fraiser

I wanted to like it. But the hero was different from my past heroes in an important quality: he was part of the ruling classes, an imperialist, an Englishman lording it over the Empire on which the “sun never set.” A bit of a wild oat–the character Sir Harry Paget Flashman, first appeared in Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s Schooldays, as one of Tom’s classmates who was expelled for drunkenness– Flashman desires to tell his side of the story and move forward. (Indeed, Fraser cleverly takes this very minor character, fleshes it out and runs with it–for more than a dozen novels.) But even Flashman describes himself as “a scoundrel, a liar, a cheat, a thief, a coward—and oh yes, a toady.”

Upon expulsion from school, he seduces (and beats) his father’s mistress; his father buys him a position in the army, and from there his (mis)adventures begin. These adventures could be a lot of heroic fun (ala Barry Lyndon), except it is all coming from the wrong perspective–from the view of those in charge. And because of that assumption of superiority, Flashman is as prejudiced and arrogant as any British officer could be at the time. And I found it uncomfortable to read. The Indians and Afghans and Irish and Italians are all stereotyped and all looked down upon and insulted. And they fare much better than the women; for the women–no matter what nationality–are not even human but mere objects for Flashman’s seductions. And he is completely unfeeling in his disposal of them.

Exotic locales, derring-do (though Flashman runs from more battles than he partakes in), and a flip irreverence is often a fun entertainment. But my heroes fight from the bottom up…not the other way around. Falstaff, who holds many of the same characteristics as Flashman, is much more likeable–but that can be because he is not an imperialist, a man who believes his own entitlements. To be honest, I simply don’t like Flashman, never mind the book.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Ironic coincidence….

There is a scene in Flashman (1969) when Flashman has been transferred from Calcutta to Afghanistan. He is explaining the condition there. Ironically, it sounds very much like Afghanistan history over the past four decades (if you change the nationalities of the forces involved). Here is what Flashman says:

“The reason we sent an expedition to Kabul, which is in the very heart of some of the worst country in the world, was that we were afraid of Russia. Afghanistan was a buffer, if you like, between India and the Turkestan territory … and the Russians were forever meddling in Afghan affairs.”

Then, ” the British Government had invaded the country, … and put our puppet king, Shah Sajah, on the throne in Kabul, in place of old Dost Mohammed, who was suspected of Russian sympathies.”

“I believe, from all I saw and heard, that if he had Russian sympathies it was because we drove him to them by our stupid policy; at any rate, the Kabul expedition succeeded in setting Sujah on the throne, and old Dost was politely locked up in India. So far, so good, but the Afghans didn’t like Sujah at all, and we had to leave an army in Kabul to keep him on his throne. It was a good enough army,…but it was having its work cut out trying to keep the tribes in order, for apart from Dost’s supporters there were scores of little petty chiefs and tyrants who lost no opportunity of causing trouble in the unsettled times, …”

I don’t know about you but this summary of the world in 1839 sounds eerily familiar to me.