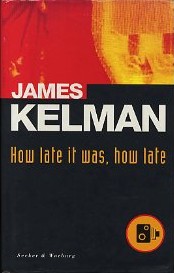

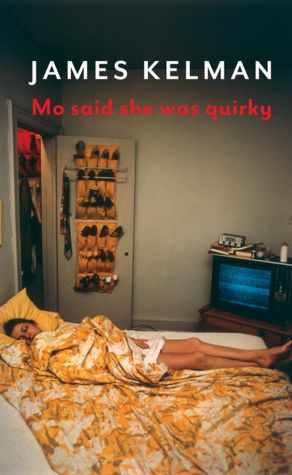

Alan Warner belongs to a certain group of writers who came of age in Scotland in the last decades of the 20th century. Those with more recognizable names would included Irvin Welsh who gave us Trainspotting, James Kelman with his unique voice of urban rootlessness, Ian Banks (who died last week) and A.L. Kennedy with their distinctive fictions, and Ian Rankin who gave us Inspector Rebus and his Edinburgh detective novels. Among these, Alan Warner seems the one who has gained less recognition over here in the States. And that is a shame.

Warner’s first novel Morvern Caller was a magnificent tale of a young woman who steals her dead boyfriend’s novel from his computer, changes the name on the manuscript and quickly and decadently burns through the advance that the novel garners, moving from her dilapidated Scottish town through the ravages of the European rave scene. A later novel with the unfortunate title The Sopranos follows a group of high school choir girls from a rural western outpost on its class trip to Edinburgh. Both novels are memorable for their voice, for the seeming accuracy of Warner’s portrayals of 16 and 17-year olds. And both are fun.

Warner returns to the same locale from which Morvern Caller and the girls from The Sopranos escape in his newest novel, The Deadman’s Pedal. And again, he is dealing with characters of a certain age, characters who are between childhood and adulthood, characters who are innocents even as they are losing their innocence.

The novel takes place around “the Port,” Warner’s fictionalized treatment of the town of Oban in western Scotland and is held together by the train line that serves the area and which is dwindling in impact. In fact the title “Deadman’s Pedal” refers to a device that on a runaway train is set to brake in the case of an engineer losing consciousness.

Simon Crimmons is turning sixteen and wants to quit school, get a motorbike, and get a job. He is considered well-to-do by his companions because his father owns a trucking company, but wealth is a relative thing, and the Crimmons family is certainly working class in comparison to the lordly Bultitude’s. In fact, Simon, the town and the novel itself are greatly aware of class distinctions. And this is a running theme throughout.

Yet it is in terms of young Simon’s desires that the class distinctions are most evident. For he is torn between the beautiful and always available Nikki Caine from the Estate houses and the enigmatic Varie Bultitude–of the town’s legendary, aristocracy. Managing such affairs is always risky and managing one between such two disparate worlds is like being on a run-away train.

When Simon mistakenly gets a job as a trainee train driver–he thought he was applying for a hospital position–he discovers the extent of these class divisions. He says to Vaire, “I’ve got the whole railway telling me I’m not working class enough and I’ve got you telling me I’m not middle class enough. This country needs to sort out the class question. As far as it applies to me.”

And to make matters more difficult, Simon’s father is caught up in it as well. He sees his son’s work on the trains as a betrayal, as his son’s working for a competitor that could ultimately put him out of business. It’s never easy being sixteen. It seems much harder for Simon Crimmons.

The joy of the novel–apart from the very real depictions of young desire, lust, and confusion–is the language itself. Some may find the dialect off-putting at first, but it quickly becomes second nature, but the narration itself is pure genius: A funeral for a dead train man is told with humor, nostalgia and poignancy; Simon’s first kiss is described as sweet, anxious, innocent and thrilling; the grounds of the Bultitude property are given an almost gothic eeriness and grandeur. (The Bultitudes are said to bury their dead in glass coffins…the aristocracy is always with us!)

Early in the novel, Simon and his friend Galbraith show Nikki the secret hideout they have built out in the wilds. They make her promise not to mention it to the other boys knowing that it is a childish thing and that the others would tease them for it. It is here that Simon and Nikki first have sex– in a short scene that is both innocent and knowing. It is a scene–positioned in his boyhood escape– that captures the very tension of this novel, the tension between innocence and adulthood, between desire and attainment, between the people and their landscape.

Alan Warner is an extraordinary writer. That his name is little known outside Britain is an injustice, but one that may be set aright by Deadman’s Pedal–a novel that is larger than its Scottish setting, a novel that is universal in its wonders, its desires, and its struggles.