“All the leaves are brown\

and the sky is gray …”

“Separation Blues” (Cover) Another Sunday Morning Tune (No. 202)

“The last words that John the Baptist said.

The last words that ole John the Baptist said.

The last words that John the Baptist said,

just before he lost his head.

I got a dose, a dose of separation blues.”

This week’s video (03/03/2024) is “Separation Blues”

March/April Music Schedule

Playing in NYC

On Saturday, April 2, 2022, I will be playing at the New Old Rock Deli in NYC. (11 Trinity Place, NY, NY 10006). It will be my first show in which I am doing only my own songs–no covers, so I am quite excited. If you are in the area, come on out, or if you have friends or relations in the area, please tell them to come on down. It is already turning out to be a fun night.

You can get tickets by scanning the QCR code on the poster above. Or by clicking on https://www.eventbrite.com/e/j-p-bohannon-new-old-rock-deli-tickets-292208793367

I’d love to see as many of you as possible. Thanks.

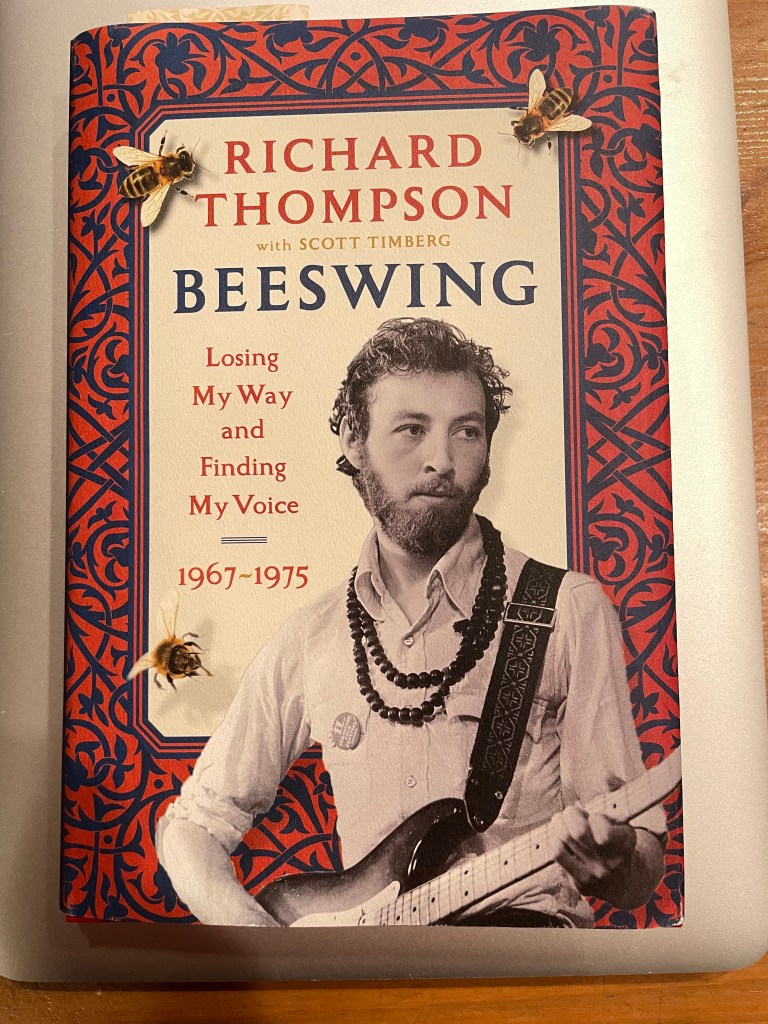

Book Review: Beeswing–Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967-1975 by Richard Thompson

Richard Thompson (© by jpbohannon 2018)

Richard Thompson (© by jpbohannon 2018)

Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967-1975

Algonquin Books, 2001

At the beginning of the pandemic, in late March 2020, Bob Dylan released a near 17-minute song, “Murder Most Foul.” Among the many, various reviews, one of the most consistent comments was on Dylan’s encyclopedic knowledge of music. The song references scores and scores of songs, familiar and un.

Well, anyone who reads Richard Thompson’s new memoir of his formative years (1967-1975) will likely also be amazed at the range of music that Thompson cites as influences. From French jazz to American blues, from Highland traditional songs to African rhythms, from classical music to British music halls, Thompson seems to have absorbed it all and writes intelligently and knowledgeably about them.

From early on, Thompson and his mates seemed to have had a vision and knew what they, as Fairport Convention, wanted and did not want. They did not want to be like the earlier “British Invasion” bands that were exploring and copying American blues and R&B and often bringing that music back to America. They wanted to use native British themes and rhythms taken from centuries-old British traditions and meld it with rock-and-roll. And thus, Fairport Convention gave birth to what became known as British folk-rock.

While admittedly influenced by Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and other American singer-songwriters and American forms (Thompson claims that what The Band did for “Americana” music with Music from Big Pink was essential in confirming what they wanted to do with British traditional music), Fairport Convention took what it learned and applied it to British themes. For example Thompson took a 15th-century British poem, married it to a 19th century Appalachian tune and electrified it (“Matty Groves”). “Matty Groves” was one of five “reworked” traditional tunes–along with three originals–that appeared on the Liege and Lief album (1969), which is unarguably considered the beginning (and high point) of British folk rock. The claim that Fairport Convention “invented” the form can be appreciated by considering the bands later begun by former members: Pentangle, Frothingay, Steeleye Span.

But Beeswing is more than a musical history. If it were only about music, its appeal would be limited. Richard Thompson’s story is a testament of persistence, resilience and a search for peace, a cultural memoir of the zeitgeist of London and the music world in those frantic years. Its focus on music arises from the fact that after leaving school, Thompson never worked at anything else but as a working musician.

And his is a story that has an almost Shakespearean plot arc.

There is much tragedy: early on, when the band is on the rise and returning from a gig, their van goes off the road killing their driver/roadie, their drummer, and Thompson’s girlfriend. Thompson himself spent a good while in hospital. At another time, a truck missed a sharp turn and plowed through the second floor rooms where he and fiddle-player, David Swarbrick, were living. There were firings–how do you fire Sandy Denny, the greatest vocalist of the day–and there were leavings. Thompson left Fairport Convention to tour with his wife as Richard and Linda Thompson. And then there was the fiery divorce that colored their North American tour.

But there is also–not so much redemption, for he was no more lost than anyone else at that time–but a sense of achieved contentment, of understanding. Much of that is due to his discovery of Sufism, which for Thompson has a “nobility of being … it seem[s] like the way human being should be.”

photo © 2007 by Anthony Pepiton

Anyone who has seen Richard Thompson in the past 20 years know him to be a gentle, humorous, friendly performer. (He is, by the way, also considered one of the finest guitarists in the world. The L.A. Times calls him “the finest rock songwriter after Dylan” and “the best electric guitarist since Hendrix.” And anyone who has attempted to emulate his acoustic guitar playing is often quickly daunted.) Whether playing with the excellent musicians he surrounds himself with or performing solo, Thompson regularly puts on shows that always leave the audience with the feeling that they have just seen/heard something memorable and remarkable.

And it is this genial manner that one observes on stage that

informs the tone and pacing of his memoir.

Richard Thompson seems very much at peace with himself–perhaps this is where the “finding my voice” in the subtitle comes from–and this feeling of contentment permeates his memoir. Although Beeswing deals with a mere nine years–from the time he was 18 years old to when he was 27–they were nine years that helped form one of the trailblazers and icons of modern music.

Performing in a pandemic year

I had planned to quit teaching at the end of the 2019-2020 school year. Pack it in, that June. I had no real definite plans besides vague ideas of going to movies and concerts, hanging in coffee houses and museums, traveling a bit and eating out a lot. I also wanted to grow my “music career.” The previous year had been a good one with nearly 40 shows, and I figured that in 2020 I would be able to increase that number significantly.

Well, to paraphrase Robert Burns, “…the best laid plans of mice and men, gang aft agley.”

School was to end in June, but the lock-down started in March. From mid-March (when I posted my last blog piece) up to then, all learning was virtual, on-line. I never again returned to the classroom. Movie theaters and museums shut their doors; restaurants and cafes as well, doing their best to stay afloat through take-out and out-door service. Traveling was limited and probably unwise and unsafe. And music venues were shuttered. That first week of “lock-down” I had three gigs cancelled. And I was glad…in full support.

Soon people started improvising. One venue set up “live streaming, virtual concerts”–I’ve done three of them. When the weather turned nice, another place used its out-door space for music (though masks had to be worn throughout all performances. An odd experience.)

In my city, we moved from take-out dining only to outdoor dining to 10% indoor capacity to 25% and then back to outdoor dining only. It was brutal on the small businesses, the fledgling pubs, the local shops. Many of them are not coming back. But many are…and will.

Me, on the other hand, I decided to put out a video on YouTube every Sunday: “Another Sunday Morning Tune.” If nothing else, it kept me busy and grew my fan-base to a large degree. I also concentrated on my songwriting and on learning the art of recording and production. That second part is not easy, and I’ve still got a lot to learn. But I got some good work done.

By the last quarter of the year, some places were opening and I was getting jobs again.

I also found a way to embed my original music onto this blog site. I hope you check it out. My songs are available on most streaming services, but here is a way you can listen to them right now.

Have fun and enjoy!

And to be sure to receive info on upcoming shows, new song releases, and new Sunday videos, please check out the Music Schedule Page above.

BOMBAST and BLUSTER and 1984

“[With Ronald] Reagan, Joan Didion wrote, “rhetoric was soon understood to be interchangeable with action.”

As quoted in Sontag: Her Life and Work by Benjamin Moser

Forty years later it has reached its apotheosis.

and

Trump’s Press Conferences and 1984

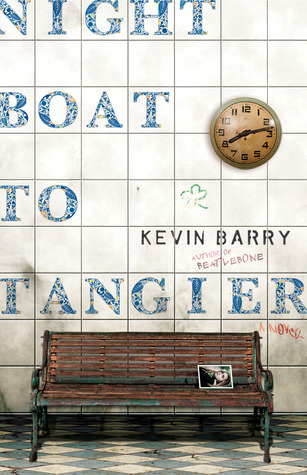

Book Review: Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry

First of all, Happy New Year to everyone!

(Many people have been waiting expectantly for 2020 to come in anticipation of some change, but I can’t know if we’ll be better off or worse come this time next year.)

But enough about that.

I want to talk about Kevin Barry’s brilliant new novel Night Boat to Tangier. A friend said that when he heard it described, it reminded him of Martin McDonagh’s film In Bruge, and sure there are two Irishmen, hapless criminal types philosophizing on their lives, past and present, and on their long relationships with each other. For me, however, I kept imagining the two protagonists as Estragon and Vladimir, not waiting for Godot but for a long lost daughter on a ferry on which they themselves used to run drugs twenty years earlier.

As Maurice and Charlie sit in the ferry terminal in the port of Algeciras, Spain in October 2018, watching the passengers boarding and disembarking on the night boat to Tangier, their pasts comes burbling up–outlining and shaping their lives for the past twenty five years. It is a past full of lost love, violence, adventure, betrayal and exile.

But it is not necessarily the plot or the characters that is the focus of this book. It is the language itself.

There are comic turns:

Ye’d be sleeping out on the beaches.

Like the lords of nature, Charlie says.

Under the starry skies, Maurice says.

Charlie stands, gently awed and proclaims–

“The heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue friut.” Whose line was that, Maurice?

I believe it was the Bard, Charlie. Or it may have been Little Stevie Wonder.

A genius. Little Stevie.*

There is darkness:

Of the dozen or so unreliable narrators narrators left in the room at this small hour, all would claim to have seen what happened next–except for Nelson, who considered himself fortunate to be on the other side of the bar–and, in fact, Jimmy Earls would claim even to have heard what happened next…and it was this ripping sound that Jimmy Earls vowed he would carry with him to the deadhouse, and with it the single dull gasp that [was] made.

And then there are passages of pure beauty:

October. The month of slant beauty. Knives of melancholy flung in silvers from the sea. The mountains dreamed of the winter soon to come. The morning sounded hoarsely from the caverns of the bay. The birds were insane again. If she kept walking, toe to heel, one foot after the other, one end of the room to the other, the nausea kept to one side only. The pain was yellowish and intense and abundantly fucking ominous. Cynthia knew by now that she was very sick.

To be sure, neither of the men is of admirable moral fiber. In fact, they are violent, treasonous, disloyal, cowardly, unfaithful drug runners.

And yet, it is the language that makes these two likable. They see the world with a sort of poetic vision–from the gutter to the stars. It is the language that gives them a method for coping with an ever-disappointing, fearful existence.

The novelist Kevin Barry . Photograph: Bryan O’Brien / THE IRISH TIMES

Language has always been Kevin Barry’s forte. His first novel, City of Bohane presented a post-apocalyptic Ireland which is described in a patois of street slang, Irish, and invention. In its originality it might remind one of Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. Beatlebone–-the novel previous to Night Boat to Tangier–takes perhaps the most public of lives–John Lennon’s–and places a western Irish mythology upon it that is dazzlingly beautiful and outlandishly comic.

The words “daring” and “original” and “beautiful” and “brilliant” are often sprinkled around reviews of Barry’s work. They are both appropriate and insufficient. He is much more than that.

*(By the way, it was neither Shakespeare or Stevie Wonder whom Charlie was quoting. It was James Joyce.)

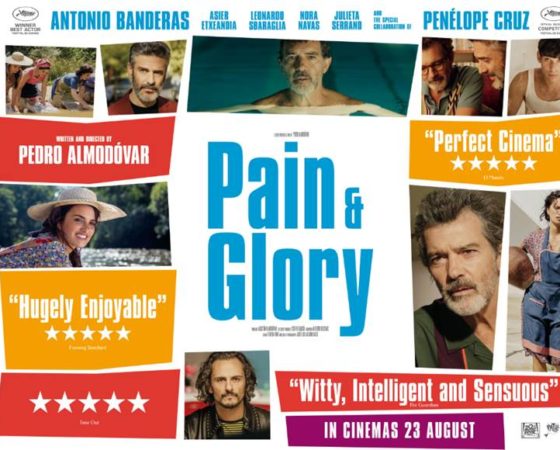

Movie Review: Pedro Almadóvar’s Pain and Glory (Dolor y Gloria)

At 6:30 a.m. on the Friday after Christmas, I found myself fully inserted into a large MRI tube. For 45 minutes I had to remain completely still while an icy course of “tracer” pulsed through my veins and a cacophonous symphony of beeps, clanks and rumblings sneaked through the noise-reducing headphones that were provided. Forty-five minutes in odd isolation gives you a lot of time to think…about pretty much everything, but certainly about one’s own mortality, about creativity and about finishing the work that one has started.

At 6:30 a.m. on the Friday after Christmas, I found myself fully inserted into a large MRI tube. For 45 minutes I had to remain completely still while an icy course of “tracer” pulsed through my veins and a cacophonous symphony of beeps, clanks and rumblings sneaked through the noise-reducing headphones that were provided. Forty-five minutes in odd isolation gives you a lot of time to think…about pretty much everything, but certainly about one’s own mortality, about creativity and about finishing the work that one has started.

I don’t know if I am unconsciously seeking out these type of things/thoughts or that I am just noticing them more and more. A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about a Rodney Crowell song titled “It Ain’t Over Yet” which deals with not giving up despite what age and time and others might tell you. I’ve played that song at two separate gigs since then. Today I finally saw a film that I had been wanting to see since it came out a month ago: Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory.

Antonio Banderas as Salvador Mallo in Pain and Glory

Almodóvar’s film deals also with the subject of mortality. (Though a two-hour film can certainly uncover many more layers than can ever be exposed in a four-minute song.) The protagonist, Salvador Mallo (Antonio Banderas) is a film-director/screenwriter beset by pains and various medical conditions who has completely stopped working and who–when not self-medicating–slips into fond memories of his past, memories triggered by the slightest moments of the present. There are memories of his mother, of his early home, of his childhood. And, at the moment, he feels that they are all he has.

Yet his film career is now the subject of art house retrospectives and a memoir piece is currently being staged by an old colleague/nemesis. But he has stopped working. There is nothing new.

He has a wonderful, solicitous secretary (Nora Navas) who continues to answer the many requests for interviews, conferences, etc–always with a “no” response. She is also charged with taxiing him to doctors and hospitals. (A wonderful throw-away line is when he asks why he is so popular in Iceland, after the umpteenth Icelandic request for him to visit.)

I have loved Almodóvar’s films since I was quite young. And if asked what it is about all of them that I remember, I might say–beside the passionate storytelling–the color. His eye for color is startling. There are many vivid reds and electric blues–Mallo’s apartment is a designer’s dream–and even the white-washed caves that the young boy and his mother (Penelope Cruz) live in pop off the screen in memorable brilliance.

Young Mallo (Asier Flores) and his mother (Penelope Cruz) in the cave where they live (before the white washing).

There has been much written about how Pain and Glory is Pedro Almodóvar’s most personal film. And that is easily understood. But since I am often teased for being a “spoiler” in any posts that I write about movies and books, I will do my best to restrain myself here. However, I will say that whatever Pedro Almodóvar is thinking, he should listen to Rodney Crowell’s song “It Ain’t Over Yet.”

Because this film is wonderful.

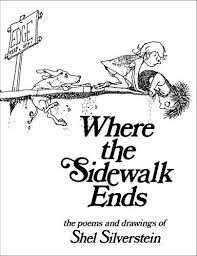

Shel Silverstein: the Little Library Where the Sidewalk Ends and Jennifer Johnson

A few years ago, in an attempt to be a cutting-edge, high-tech institution, the powers-that-be decided that the school I teach in didn’t need a library. The library is superfluous, they claimed. Students have all the information they need on their phones in their hands. (As if information was all that students need.) And so, quickly, the library was gutted, the librarian dismissed, and the books were donated, destroyed, or “disappeared.” From its ashes rose a Maker-Space and a Learning Commons. (If you are not currently involved in modern education, don’t ask.)

“The Library Where the Sidewalk Ends” on Valentine’s Day

A few colleagues and I couldn’t imagine a school without a library, so we built our own. A “little library” it was, and ones like it appear in neighborhoods, towns and cities throughout the U.S. (I once was at a ribbon-cutting ceremony for such a library on the porch of a bar in Key West, although it was much more of a Key West celebration than a library opening.)

Anyway, the library thrived with people taking and leaving a variety of books, CDs, and even art works.

The library itself was located in an odd place in the middle of campus. There was a cement sidewalk that jutted into a swatch of grass and then just ended. When I would announce new additions to the library, I would refer to it as “the library WHERE THE SIDEWALK ENDS.”

And every student and every adult knew what I was referring to: the delightful first collection of poems by Shel Silverstein that every student had loved as a child and every adult of a certain age remembered reading to his or her own. The poems in Where the Sidewalk Ends are silly, irreverent, charming, and knowing. It’s the silly irreverence that children most love: as if the adult Silverstein—unlike other adults in their world— was clued into the fears, the joys, the silliness, the incomprehension, the absurdity with which they view the world.

And every student and every adult knew what I was referring to: the delightful first collection of poems by Shel Silverstein that every student had loved as a child and every adult of a certain age remembered reading to his or her own. The poems in Where the Sidewalk Ends are silly, irreverent, charming, and knowing. It’s the silly irreverence that children most love: as if the adult Silverstein—unlike other adults in their world— was clued into the fears, the joys, the silliness, the incomprehension, the absurdity with which they view the world.

Yet, Silverstein was more than a children’s poet. He began as a cartoonist, and a successful one. It was his cartoons that prompted his publisher to suggest a book of poems. He was also a playwright–David Mamet called him his best friend–with over 100 one-act plays under his belt.

And he was a prolific songwriter. He had a number of hits with what could be called novelty

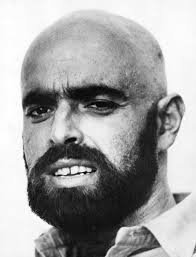

Shel Silverstein

songs: “On the Cover of the Rolling Stone,” “Sylvia’s Mother,” “A Boy Named Sue,” and the “Unicorn” song ( you know, “green alligators and long necked geese… .”) But he also had a solid stable of songs recorded by a slew of people: Dr. Hook and his Medicine Show, Loretta Lynn, Bobby Bare, Belinda Carlisle, Waylon Jennings, Emmylou Harris, Marianne Faithful, Johnny Cash among others. I remember the first Judy Collins’ album I ever bought featured a rousing protest song called “Hey Nelly Nelly.” I didn’t recognize the name at the time, but it was written by someone named Shel Silverstein.

And so it comes to a song I have recently rediscovered. I was buying tickets to see Todd Snider in concert and was looking for the one Todd Snider album I own. I couldn’t find it. So instead I pulled out a Robert Earl Keen album West Textures which features a charming Shel Silverstein song, “Jennifer Johnson and Me.” (Snider mentions a Robert Earl Keen song in one of his own songs which is what originally had driven me to this album.)

Anyway, the song tells the story of a man who finds in an old suit jacket pocket a black-and-white photo (‘three for a quarter”) from an arcade photo booth. The picture is of him and an old girlfriend, Jennifer Johnson. The singer is well into adulthood now, and the photo is of him when he was in late adolescence, sitting with Jennifer Johnson.There is a sweet nostalgia in his memories of their innocence, their hope, and the belief in “forever.”

It’s a sweet song, and I opened up with it on Saturday. I think I will keep it in my set list. Here’s the tune, by Robert Earl Keen: