A few years back, after a particularly mind-numbing conference, a number of colleagues and I repaired to a little hole in the wall on 3rd Street called St. Jacks. The place, hung with erotic black and white photos and glazed with a patina of dust and grime, look as if it were waking up after a rough night. There were no other patrons and, if I remember right, the “kitchen” had been closed for a very long time.

The place was named after a character in the eponymous novel by Paul Theroux. (It was later made into a film by Peter Bogdanovich which has a weird history in itself.) At the time, I was reading Robert Graves The White Goddess, his archeological/anthropological/mythological treatise on pre-Grecian religion, primarily the matriarchies of early civilizations that spread throughout Northern Europe and the British Islands from the south.

Several of my colleagues filled the booths, and four or five of us sat at the bar. The bartender’s name was Cinammon. And she was good. In fact, she is perhaps the best bartender I’ve ever encountered. I put the book I was carrying on the bar, and preceded to talk to my colleagues and to Cinnamon.

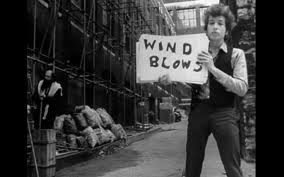

Yes, her mother had named her after Neil Young’s “Cinnamon Girl.” And yes, she asked me about the book, but no, she had never read Robert Graves, nor had ever heard of him. After a while, the others wandered out, but my friend Jim and I stayed for a few hours more. The two of us–and Cinnamon–talked about the things we always do when sitting at a bar: music, film, and books. It was a good day.

But now comes the amazing part. We attended a similar conference, one year and a day from that original conference. And like the first one, we all went to St. Jack’s after the conference. And Cinnamon was still tending bar. I hadn’t been in the place since that first time, a year ago. But when I sat at the bar and ordered my pint she asked me if I had finished The White Goddess.

Now, a good bartender should remember the drinks of his regular customers. A very good bartender will remember the drink of the occasional customer. But it is an extraordinary bartender who remembers not only the drink of a customer whom she had served only once a year ago, but remembers the book he was reading at the time.

Jim and I stopped a few more times after that, but Cinnamon left a short while after, left to become a legal secretary. It is a great loss to the bar-tending profession. And St. Jack’s itself is now gone (It had once got in trouble with the Thai government for using an image of the King of Thailand on an advertisement that ran in one of the free city papers. How they came across it is a wonder? Much of the novel/film St. Jack takes place in Singapore and what was then Siam.) And I have never warmed to the new place.

And for various reasons–I had just purchased James George Fraser’s The Golden Bough which reminded me of The White Goddess, and I have been lately banging out “Cinnamon Girl” on the guitar whenever I get a moment to myself–I have been thinking about St. Jack’s, about The White Goddess, and about Cinnamon.

So here, in memory of the greatest bartender I ever met is Neil Young singing “Cinnamon Girl.” And as a treat, it is not his familiar fuzz-driven guitar version of the song, but a different version of Neil by himself on the piano from his upcoming album “Live at the Cellar Door.” Enjoy: