Doc Holliday b. August 14, 1851. (illustration 2016 by jpbohannon)

“There’s no normal life, Wyatt. There’s just life.”

From the movie Tombstone,

featuring Val Kilmer as Doc Holliday

Doc Holliday b. August 14, 1851. (illustration 2016 by jpbohannon)

“There’s no normal life, Wyatt. There’s just life.”

From the movie Tombstone,

featuring Val Kilmer as Doc Holliday

The seal and John talk on the beach at Clew Bay 2016 by jpbohanno

And I’ll tell you another thing.

Go on?

All this …

He swings his head to indicate the world beyond–he’s got a fat stern head like a bouncer.

Fucked, he says.

You don’t mean…

I do, John. It won’t last.

You mean everything?

The works, he says.

But it sounds as wherks.

The wind, the waves, the water, he says.

But it sounded as wawteh.

It’s all in extra time, he says. It’s all of it fucked, son.

Mostly what John cannot get his head around is the Scouse accent.

And so it is 1978 and we are in the West of Ireland in the town of Newport in County Mayo. We have booked a B&B in the town before heading out to the uncle’s farm, knowing that he and Ana and Carmel and Tony would insist that we stay with them. But we are twenty-four and will not be bridled. That night there is a ceilidh in the local pub and all the aunts and uncles and cousins and friends–long heard of but never met–gather and we the Yanks are the guests of honor. We crawl back in the wee hours but once again in the morning the whole crowd is together at Mass and when we leave we speak to a few new faces on the church steps which gives the priest time to beat us to the pub. Two nights earlier in Kerry we had played guitar in an old sheep-farmers pub, but the caravan of hippies that showed up with their instruments wanted only country-and-western which was not my strong suit. But I was able to give them some Woody and some Hank nevertheless, and then a few rebel songs. It was a long and dangerous night on the Kerry road.

And at the same time, unbeknownst to me, John Lennon was in my uncle’s town, hiding, according to Kevin Barry’s brilliant novel Beatlebone. I would have loved to have met him, but in the novel, he was not in a very good state of mind. And he was trying very hard to stay under-the-radar.

The novel is built on the fact that in 1967 John bought Dorinish Island, one of the many small islands off the west coast of Ireland. He had great plans for it, but few of them succeeded. And he only visited it a few times.

But now in Beatlebone, it is a decade later, John’s creativity seems to have flat-lined and his life consists of baking bread and raising his young son, Sean. He rarely leaves his New York City high-rise. He is not feeling right. He has been through Primal Scream therapy, but is still forever haunted by the father who abandoned him and the mother who lived around the corner from the aunt who raised him.

And so, he comes to Ireland to spend some time on his island and to heal himself.

Neither of which is an easy task to complete.

John is chauffeured by an irascible driver named Cornelius O’Grady, who very well may be a shape-shifter and who has taken the responsibility to hide John from the press, which has been alerted that he is there in the West.

Cornelius is open and honest and uncowed by his famous fare. In fact, his advice and wisdom and observations show no sign of tact or concern. And his and John’s conversations are great fun. (At one point, Cornelius convinces John to grease back his hair, wear Cornelius’s dead father’s eyeglasses–he is already wearing the dead man’s suit– and say that he is his stuttering cousin Kenneth from England. All so that they can go undetected into a pop-up moonshine pub in the hills of Mayo.)

It is after escaping the hotel that Cornelius has stashed him in and spending the night in a cave on the beach that John has his conversation with the seal and where he realizes his new album BEATLEBONE. He maps the entire thing out in his head before he is gathered up by Cornelius. He is sure that it will be the album that will change his reputation, his legacy forever.

As I was reading Beatlebone for the first hundred pages, I wanted to text, e-mail, call friends and tell them that no more novels need be written for this is the definitive example. (I lean towards hyperbole.) The language itself is exquisite and daring and

The novelist Kevin Barry. Photograph: BryanO’Brien/IRISHTIMES

imaginative. And that is what one would expect from Kevin Barry, whose greatly awarded City of Bohane was a tour-de-force of underworld argot and Dublin slang positioned in a post-apocalyptic Ireland.

Beatlebone is a novel that is so fresh, so funny, so beautifully amazing and accurate that one finds oneself reading out passages to anyone who listens. (Another fault of mine.) There is one oddly placed chapter where the author talks about his research for the novel that, while fascinating, might better have been placed at the end or the beginning of the novel. But that is a minor quibble.

The rest is perfect. So much so, that many may give up writing fiction entirely.

The New York Times, in its review of Ben Ehrenreich’s book The Way to the Spring: Life and Death in Palestine, posted the picture below:

photograph by Ruth Fremson/The New York Times

It is a photograph of unbridled joy, curiosity and innocence set in a refugee camp against the bombed out ruins of Gaza. The happiness of childhood trumps–at least in this moment–the nastiness of the adult world around them.

This photograph reminds me very much of the first half of Hany Abu Assad’s film The Idol (Ya Tayr Al Tayer). It is a fictionalized account of the true story of Mohammed Assaf, the Palestinian wedding singer who sneaked across the border from his Gaza refugee camp and traveled to Cairo to compete in Arab Idol (the Arab version of “American Idol”). The film is divided neatly into two halves. (Though it is an awkward transition from the first to the second half.)

The first-half begins with a group of young children, riding their bikes, running from bullies, scraping together money, fishing (and then cooking and selling those fish). There is a sense of pure joy and freedom and hope. Except for the background of bombed-out buildings, exposed rebar, enormous piles of rubble and trash and ubiquitous destruction, the scenes could have been written for Hal Roach’s Little Rascals.

All photos from “The Idol” press kit.

The children want to form a band. The 10-year old Mohammed (Qais Atallah) and his 12-year old tom-boy sister Nour (Hiba Atallah) recruit their friends and begin performing. Mohammed’s talent is evident; his voice is mature and controlled beyond his age. His sister’s charm and grit and ambition push the band forward, and they begin getting hired to play at weddings. (Nour’s being female is a problem. They cannot get hired if they have a female in the band and no one would hire them without her musicality. So she hangs in the background, behind the others, playing guitar and wearing her ever-present backwards baseball cap.)

Young Mohammed (Qais Atallah)and his sister Nour (Hibba Attala)

And they are good. Carried by Mohammed’s voice.

When Nour collapses from kidney failure, the band dissolves, but Mohammed vows to earn enough money singing to get her treatment–thus the quest to appear on Arab Idol. The actual quest begins the second half of the film when Mohammed (now played by Tawfeek Barhom) is 18.

Life hasn’t changed much in the seven years that have elapsed. It may have gotten worse. There are still power shortages, travel restrictions, destruction, hopelessness. But Mohammed is determined, especially when encouraged by the girl he met while his sister was getting dialysis.

This is not a spoiler. It is the fact that the film is based on. Against, incredible odds, Mohammed Assaf rises to the top of the competition. And it is here that one witnesses the true joy of the film.

Mohammed Assaf (Tawfeek Barhom) on “Arab Idol”

Every neighborhood, every household, every town square is filled with proud Gazans watching Mohammed on Arab Idol. Their pride and joy is palpable. There is cheering, fireworks, embraces, flag waving. These people have not had a lot to cheer for, and now they do and it is cause for celebration.

It would be disingenuous to say that The Idol is not a political film, for of course it is. The politics, however, are subtle and act as a patina to a classic story of realizing one’s dreams. It is a joyous film, all the more remarkable for taking place in what appears to be such a joy killing space. And the realizations of Mohammed’s dreams are felt vicariously by the crowds that gather around televisions, big and small, and watch his ascent.

Hany Abu-Assad, who shares writing credits with Sameh Zoabi, has crafted an emotional film that never gets schmaltzy. There is angst and happiness, frustration and success, danger and death and victory and love. But it is all done with an even-hand and a simple narrative. Again, the politics are there–you cannot see Gaza and not wonder how or why? But, that is never the thrust of the film.

It is rare these days to see a film set in the Middle-East in which afterwards one comes out of the theater smiling and happy. Hany Abu-Assad has created such a film. And our joy is not simply for Mohammed Assaf, but for the Gazan people themselves. Sure their lives will remain unchanged for the most part, but the music competition has given them something to be proud of.

Silk Screen illustration 2016 by jpbohannon.

Winston Churchill called his bouts with depression “having the black dog on his back.” This was not original with him, but was a common saying, referring more often to moodiness than depression. One historian likened it to the phrase “getting up on the wrong side of the bed.” But nevertheless, the phrase has been attributed to Churchill and ever since been associated with depression.

God knows, the world that Churchill saw certainly could buckle the strongest man’s knees.

And so it seems to be these past few months, as well. From Paris to Brussles to Orlando to Dallas to Nice to Turkey to everyday traffic-stops, there has just been an onslaught of horrific and discouraging news. President Obama, in his speech after the Dallas shootings, said that “this is not who we are.”

But I wonder. Not we as Americans specifically–although I do wonder about that–but we as a species.

Sure, I know the heartwarming and hopeful stories as well: from high-school kids doing serious global service to individual neighbors coming together to help another in worse shape than they, from those who put their lives on the line to those who fight against power when it seems determined to crush the weak. I know people whose every thought seems to be how to better the lives of the sick and dispossessed, the impoverished and the abused.

And yet these past few months have been relentless.

Last week, I read two novels by Dag Solstad, Shyness and Dignity and Professor Andersen’s Night. Both deal with teachers–Norwegian literature teachers–at the end of their careers. They both (a high-school teacher and university teacher respectively) question the value of the literature they profess. (Both are teaching Ibsen.) The struggle to make students realize the value of literature has been ongoing throughout their career–that is always the natural give and take between student and teacher, although both feel it increasingly worse– but now they feel that that value is questioned by society itself. From evolving technologies–and the distractions they provide–to current pedagogical trends and goals that emphasize success in a future career, they feel out of place, like dinosaurs, supporting a cause that is no longer relevant in the ultra-modern world.

And it is easy to believe that.

As hundreds are gunned down, blown-up, crushed, drowned, stripped of their homes, it is hard to rationalize the need to read a 150 year old Norse play, or a 450 year British play , or a 2500 year old Greek. Novels, poetry, drama, short fiction…it all feels so powerless against men with efficient guns and deficient ideas.

And yet, never before has it been so important.

Study after study has linked reading literature with an increase in the development of EMPATHY. Even the youngest teenager, after reading To Kill a Mockingbird, understands on the simplest of levels, the importance of “walking in another man’s shoes.” Reading has always been a way of experiencing different lives, different cultures, different ideas. And this is what it needs to continue to do. It is our insularity, our tribalism, our fear of (and intolerance to) the “other” that is that root of much of the world’s pain and horror.

I KNOW that art, music, literature, theater, dance are more than just “nice things” for entitled leisure. They are essential to us as a species.

I KNOW these things to be true. But these days I do not FEEL it.

But I must continue doing what I do, nevertheless: read and write.

However, as I read this, the “black dog” is wagging its tail frantically and banging up against the door.

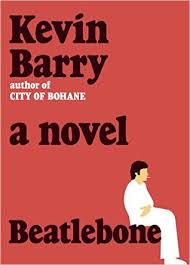

“The Quiet Christmas” illustration 2016 by jpbohannon

In Camus’ iconic novel The Stranger, a man murders another and spends the second half of the novel trying to understand and rationalize both his actions and their consequence. Despite Camus’ distancing himself from the term, The Stranger is the quintessential “existential” novel.

As is the Norwegian writer Dag Solstad’s novel Professor Andersen’s Night.

But unlike Camus’ Meursault who kills an unnamed Arab on a beach in Algiers. Professor Andersen does not kill but witnesses a murder, on Christmas Eve night in the apartment across from his. And his internal struggles are every bit as Sisyphean as Camus’ protagonist.

Dag Solstad (photo from http://reading-randi.blogspot.com/2010/11/tanker-om-bok-dag0solstad-professor.html)

In Solstad’s novel, a literature professor in Oslo who specializes in Ibsen is a loner who enjoys both his solitude and communal traditions. (Shyness and Dignity—Solstad’s first novel translated in English–featured a high-school literature teacher who had his moment of crisis while teaching Ibsen.) Thus on Christmas Eve night, Professor Andersen dresses in a suit and tie, cooks a traditional Christmas dinner and opens the two gifts under the fully decorated, full-sized tree while enjoying his after-dinner coffee and cognac. It is the perfect traditional Christmas Eve… except that he is willfully alone.

To compensate, he draws the curtains of his apartment window and stares out at the festivities in the windows across from him. In the various windows, he sees people sitting at meals, standing convivially with drinks in hand, sitting around distributing gifts.

And one man strangle a woman.

Naturally, Professor Andersen is shocked. He reaches for the phone, dials the police, but hangs up before he is connected.

He cannot make the call.

Through the holidays and for the next month after, he is obsessed with the murder and with his decision not to call. He searches the various newspapers for mention of the murder or mention of a missing woman. He goes over to the apartment building and discovers the man’s name. He watches from behind the curtains the man’s comings and goings.

Book cover of the Norwegian paperback edition.

At a dinner party, he considers telling his friends, all radicals when they were together in college, but now quite comfortable in their professions. He knows that they would not understand his decision, that their advice, concerns, discussion would be far off the mark.

And so he examines his every thought–past and present. Is he committed– as a member of a civilized society–to tell? Or does his championing of the individual commit him not to tell? He considers his options, his mental growth, his expertise in literature (where, after all, he is consistently analyzing men who are put into crisis and must act). He examines his soul, his basic beliefs, to a degree that most of us do not.

And then he meets the murderer–unintentionally, in a sushi restaurant. Afterwards, he invites the man in to his apartment for a drink.

Even this encounter, does not quell his internal wrestling. He has a quasi-religious experience, believes he has received some sort of divine grace. And yet still he must ponder the consequences of both his acting and not acting.

Professor Andersen’s Night is a short, but dense, novel. The internal dialog that Professor Andersen conducts is wrought by philosophical quibbling, rich in existential anguish, and accessible in its “everyman” applicability.

Like Elias Rukla in Shyness and Dignity, he too comes to doubt all that he has believed and professed, to second-guess his career and all that it purported to do. And he too must fathom, exactly what it is he stands for and where he goes from here.

Professor Andersen’s Night is a thoughtful novel–a novel of ideas and questions. It is a novel that stays with you for the better.

And makes one consider where any of us actually stand.

Poster for Maggie’s Plan

A general statement would be that I greatly admire Ethan Hawke’s movies. (His “serious” movies. I’ve never seen his more commercial work.) Just as true is the fact that I rarely like the characters Ethan Hawke plays in these movies. Too often they seem to me to be self-involved posers. To wit, while I truly love the three Richard Linklater films (Before Sunset, Before Sunrise, and Before Midnight), I do not like the Ethan Hawke character, particularly in the last. (As his success as a writer grows in these movies, so does his self-involvement and pomposity.) I believe that Hawke himself to be an interesting, knowledgeable and intellectual artist, honest about his art and serious about his decisions, but playing one on film is another thing. My god, the most annoyingly self-centered intellectual twit of all time is Hamlet, and Ethan Hawke’s version of the character is true to form. Though I love this version of Hamlet, I’m pretty glad when Hawke’s Hamlet gets it in the end (by gun this time rather than sword.)

Having said that, Maggie’s Plan is a sweet, whimsical film, filled with quirky performances and centered around the Ethan Hawke typical role–a wannabe novelist, anguishing over his work, and pretty sure the world revolves around him.

Greta Gerwig as Maggie. Photo Credit: Kristin Callahan/ACE/INFphoto.com Ref: infusny-220

Quickly, the film concerns a young girl in New York, Maggie (Greta Gerwig) who wants to get pregnant. She finds a potential sperm donor–a friend from her undergraduate days in Wisconsin (Travis Fimmel). However, at the same time she meets John (Ethan Hawke) a professor at New York’s New School where she also works.

And so, they begin an affair.

John is writing a novel, and is not getting the support he wants from his wife Georgette, a superstar intellectual played by Julianne Moore, who hilariously uses an accent that channels Madeline Kahn from her Young Frankenstein and Blazing Saddles days. John begins having Maggie read his work-in-progress, which is basically how he seduces her.

Quickly Maggie and John get married, they have a child, and just as quickly she wants to give him back to his wife. His self-centeredness is simply too much to cope with. So elaborate plans are made to “return him.” (This could be the “Maggie’s plan” of the title, or it could be her strategy to have a child.)The plot to get the original husband and wife together is humorous and flawed and is the gist of the film.

Helping Maggie along are her two friends Tony and Felicia, played by Bill Hader and Maya Rudolf. Both of these actors continue to grow their talents in a variety of interesting projects, and in Maggie’s Plan, they make the most of the minutes they are on the screen.

Maggie herself is quirky and likeable and somewhat innocent. Her wardrobe (which seems to be what can only be called 1950s Wisconsin-chic) places her as an outsider in savvy New York, and her contact with the intimidating Georgette only underscores this.

Maggie (Greta Gerwig) reveals her plan to Georgette (Julianne Moore)

Maggie’s Plan is light fare–so much lighter than director Rebecca Miller’s previous work. There is a sweet and satisfying (though hinted at) ending and there are some wonderful performances. (Again, Julianne Moore is hilarious, and seems as if she is enjoying playing so over-the-top.)

It is not the kind of film where one goes for coffee afterwords to deconstruct and analyze it–and it is not intended to be such. Maggie’s Plan is simply a pleasant way to pass a few hours in the summer.

“Broken Umbrella” illustration 2016 by jpbohannon

Dag Solstad, a novelist and playwright, has won numerous prizes for his writing, including the prestigious Nordic Prize for Literature. He is the only author to have recived the Norwegian Literary Critics Award three times. This is the first English translation of his work. Solstad lives in both Oslo and Berlin.

Back Cover copy of Shyness and Dignity by Dag Solstad

And most of us have never heard of him.

In general, we Americans are very ignorant of writers in other languages. It is not our fault (despite our staunch embrace of our mono-lingualism). American publishing houses take very few chances with translated works. Of course, there are exceptions. Publishing houses such as Europa Editions, Graywolf Press, and Vintage have been steadfast in bringing forth translated novels. And every so often they catch on. Elena Ferrante is a phenomenon; Jo Nesbo continues to thrill; and the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo series was a publishing behemoth. But in general, we are isolationists when it comes to reading.

To wit, Shyness and Dignity, Solstad’s first novel to be translated into English, was published in Norway in 1996 and in the States in 2006. It was his first novel translated into English–thirty-seven years after his first book came out in 1969.

(One would think that his books covering each of the FIFA World Cups from 1982 on would have introduced him to Americans. But then again, we as a nation are just beginning to watch soccer; obsessive reading about it is probably a bit down the road.)

And so we have Shyness and Dignity. (As of now, there are three novels translated: Shyness and Dignity, Professor Andersen’s Night, and Novel 11, Book 18.)

Elias Rukla is a middle-aged teacher, teaching Norwegian Literature in a National high-school in Oslo. He is frustrated by his work, has lost belief in the relevance of what he professes, and feels useless in the new educational arena. One day, after his last class, a class in which he felt he was being particularly trenchant, in which for the first time in a while he believed he had said something original, something worthwhile, and in which at his greatest moment of insight, he was interrupted by the bored groan of one of his students, Elias left the building for the day.

It was raining, he was prepared, but his umbrella would not open. Another moment of frustration. Many attempts at opening it escalated into a battle. He sliced his hands with the umbrella ribs, threw the umbrella on the ground and began jumping on it. As students gathered around to watch their teacher wrestle with this inanimate object, he lashed out, calling one tall blond student a “fat snout” and a “damned bitch.”

At that moment, he realized his career was over.

This scene is actually a very small part of the novel. The opening frame, if you will. As he wanders the streets of Oslo, considering the irreparable consequences of his actions, he thinks of how he would tell his wife.

And then he thinks of how he had met her. And then he thinks of the friend who had introduced them. And then he thinks of what he and she and the friend had once been and had now become.

It is a story of hopes unrealized, optimism and activism dampened, and life soullessly borne.

We follow Elias through his graduate school days and his fascination with a young philosophy student who is the darling of both his peers and his professors. Not only is Johan Corneliussen a prodigy in philosophy–particularly Kantian philosophy–but he is a prodigy in life. As Elias explains:

Johan Corneliussen moved without difficulty from ice hockey to Kant, from interest in advertising posters to the Frankfurt school of philosophy, from rock ‘n’ roll to classical music. Operettas and Arne Nordheim … Music, ice hockey, literature, film, soccer, advertising, politics, skating.

It was this total immersion into life–so different from the shy and insecure Elias Rukla–that was Corneliussen’s attraction. And Rukla became his shadow, inseparable friend, partaking in it all and basking in the reflected adulation that was directed towards his companion.

As we follow the college students through their various interests and politics, their associates and lovers, we also see the crumbling of young certainties. Except that Elias retains his much further into life.

It is struggle with his umbrella that brought about this realization that all has changed, his career, his wife, his beliefs, his interests.

And with this meandering journey homeward, he has reviewed his entire life up to this very moment, this moment when he feared what he would say to his wife. All had changed and he was just realizing it now.

Solstad’s novel is an examination into what makes us act, what compromises we make, and what indignities we are willing to bear. It is an internal examination, not of conscience, but of consciousness. It is a somewhat dreary look at the dampening of hope, the degrading of cultural literacy, the momentum of capitalism. Solstad’s sentences are long and meandering, walking through a paragraph much the way the Elias walks through the streets of Oslo, but each one is perfect.

Each one brings us a few steps closer to the destination that Elias must ultimately reach.

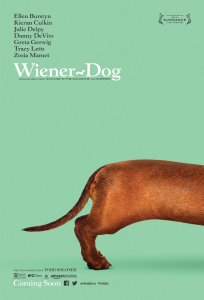

“Wiener-Dog” illustration 2016 by jpbohannon (based on one-line Picasso drawing of his dog LUMP)

I have always had a thing against dachshunds. I believe it stems from cartoon watching when I was a child. Back then, if you were a dachshund in a cartoon, you were typecast: you had to wear a monocle, smoke a cigarette in a long cigarette holder and dress like a Nazi officer. (German Shepherds were often the guard dogs, the grunts, but the dachshunds were ALWAYS the officers.) Anyway, the prejudice stuck, and I am still not fond of dachshunds.

So against my better instincts, I went to see Todd Solondz’s Wiener-Dog. A quirky series of vignettes, performed by an interesting cast, and tied together by a dachshund who is passed from one owner to the next. And while the dog itself has little to do with the different stories, it is the tie that binds, so to speak.

Movie poster for Todd Solondz’s Wiener-Dog

We begin with a young boy (Keaton Nigel Cooke), a cancer survivor, whose father brings the dachshund home to the boy as a companion. The parents are self-absorbed; the boy is understandably interested in death and life and birth; and the mother, played by Julie Delpy, tries to answer his questions honestly. However, she has difficulty with this. (The story she tells to explain why it is important to have the dog spayed is extraordinary in its outlandishness. At one point in the story, the man in front of me moaned at the political incorrectness in her tale.)

The parents cannot handle the dog in their pristine house–who has gotten violently and graphically sick–and quickly take it to the vet to be put down. Here the vet’s assistant (Gretta Gerwig) steals the dog and brings it home. While shopping for dog-food, she meets an old high-school friend (Kieran Culkin) with a heroin problem. He is driving across country to Ohio to inform his brother of their father’s death. For some reason, she decides to accompany him. The dachshund sits on her lap throughout most of the trip and does nothing. Much like Gerwig herself.

Although the wiener-dog is given to Culkin’s brother and his wife in Ohio (Connor Long and Bridget Brown) at the end of Gerwig’s vignette, it next appears in New York City with a film-school instructor, Dave Schmerz (Danny DeVito). Schmerz is waiting for his big break; his screenplay has been sitting in offices in Hollywood and it is obvious that the agents are not taking him seriously.

He is also greatly disliked by his students who feel he is a dinosaur and has nothing to offer their uber-hip selves. (One hipster film-student explains just how out of touch Schmerz is by claiming he probably has a box-set of Curb Your Enthusiasm, still watches Seinfeld, and thinks Woody Allen is terrific. Wow!)

And while DeVito’s character puts the dog in an adorable yellow dress and walks her through Manhattan on his way to school, his story is sad and does not end well.

And so somehow the wiener-dog appears next with a curmudgeonly old woman (Ellen Burstyn). She is bitter about her life and her life choices. After her drug-addled granddaughter visits and asks for a very large check to help finance her artist boyfriend, (which she writes), the old-woman is visited by a series of versions of herself–selves she would have been, if she had been different. (This hearkens back to Danny DeVito story, where the teacher is ridiculed for his screenwriting mantra “what if.”)

This story does not end well either.

Wiener-Dog is beautifully shot, particularly the scenes of the little boy and the dog, of the dog and Ellen Burstyn, and the suburban landscapes that Gerwig and Culkin drive through. Full of light and color, they capture an America that always seems to have something hidden right under the surface. And the performances of Keaton Nigel Cooke, Danny DeVito, and Ellen Burstyn are poignant and memorable.

And there is a jokey Intermission sequence where a large Dachshund walks across the American landscape to a cowboy-type theme song, “The Ballad of Wiener-Dog.” It is fun and silly and for a moment takes our mind off some of the more unsettling ideas that lie beneath the tales that we are seeing.

Wiener-Dog is described as a dark comedy. I am discovering that the more I think about it, the darker it becomes.

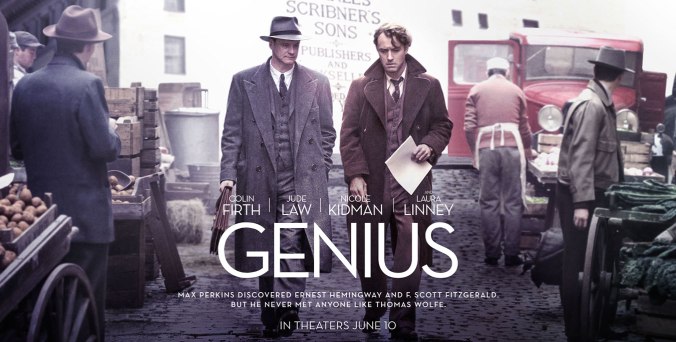

There is a scene towards the end of Michael Grandage’s film Genius where Scott Fitzgerald (played by Guy Pearce) is in Hollywood, drinking Coca-Cola and working hard on The Last Tycoon. He has failed and given up on screenwriting, he is trying to keep his drinking in check, and he is hopeful for his new work. I mention this because it is the fourth time I have seen (or read about) this moment in the last two months. It is a pivotal point in Fitzgerald’s short life, and Fitzgerald and his world certainly seem to be “trending” these days. (A film version of The Beautiful and Damned is now in production; Z: The Beginning of Everything is airing now on Amazon; and Stewart O’Nan’s West of Sunset hit the shelves in the spring.)

Genius is about Fitzgerald’s world. He is only a minor figure — borrowing money, taking care of Zelda, scolding Thomas Wolfe for ingratitude. Hemingway (Dominic West) also puts in a brief appearance and when he does, he seems the most pragmatic of the lot.

But Genius is not the story of these two giants of American letters. It is the story of their editor Max Perkins, and his overlarge, prolix client Thomas Wolfe.

Colin Firth as Max Perkins and Jude Law as Thomas Wolfe in Michael Grandage’s Genius

Genius is based on A. Scott Berg’s book Max Perkins: Editor of Genius and concentrates primarily on his relationship with and molding of Thomas Wolfe. And while the book title implies that Perkins was the editor of men of genius, such as Fitzgerald and Hemingway, the film leaves one wondering whether it was Perkins who was the genius after all.

Wolfe (Jude Law) explodes into Perkins’ office at Scribner’s, expecting to have his manuscript rejected by yet another New York publisher. When Perkins (Colin Firth) informs him that they want to publish him, a very close and productive relationship begins.

Wolfe is overlarge in his personality and writing, and Jude Law plays this for all it’s worth, chewing up every scene he is in, which is the majority of the film. His gregarious, boiling over energy is in stark contrast to Perkins whom Colin Firth plays with reflective gravity and business-like rigidity. The contrast seems as if it would sabotage the relationship, but it does not.

There are other issues buried much deeper.

When Wolfe first comes to Scribner’s, he is being supported and promoted by his lover, Aline Bernstein (Nicole Kidman), who quickly becomes jealous of Perkins’ influence on and success with Wolfe. Perkins’ wife Louise (Laura Linney) also is concerned with the amount of time that her husband is spending with his new client; (He needs to spend time, Wolfe’s second novel is over 5000 pages long when he brings it to Perkins.) She counters his argument that only once in a lifetime comes such a writer as Wolfe with the fact that only once in a lifetime will he have his daughters around him.

His responsibility to Wolfe overrides her logic.

But it is hinted at that there is a deeper foundation to Wolfe and Perkins relationship. For Wolfe, Perkins has become a father-figure, replacing the father that he lost when he was a young man and who he has been writing about ever since through two very large novels. For Perkins, Wolfe was the son he never had.

And like many father-son relationships, there has to come a break, when the son feels he must strike out on his own. When Wolfe makes this break, we know it will not end well.

Genius is a wordy film, as any film about Thomas Wolfe needs to be. It is hampered, perhaps by scenes of writing and editing, scenes that never translate well to the screen, and by the melodrama of Wolfe’s and Bernstein’s affair.

Perkins and Wolfe (Firth and Law) editing Of Time and the River

But it is an honest film, built on the back of Colin Firth’s nuanced, quiet performance. Allowing Law’s Wolfe to rage and celebrate and orate and revel, Firth’s Perkins builds a quiet portrait of a feeling man, conscientiously doing the job he loves and loving the man who is his job.

Filmed in a palate of brown and greys (contrasted brightly when Wolfe visits Fitzgerald in Hollywood), it is a film about words not images. About a man of so many, many words, Genius is a tragic view into the blistering comet that was Thomas Wolfe. More importantly, it is the story of Max Perkins, the man who burnished Wolfe’s blazing talent for the world to know and remember.

The Official Web Site of LeAnn Skeen

Grumpy younger old man casts jaded eye on whipper snappers

"Here is my secret. It is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.."- Antoine de Saint Exupéry

Of writing and reading

Photography from Northern Ontario

Musings on poetry, language, perception, numbers, food, and anything else that slips through the cracks.

philo poétique de G à L I B E R

Hand-stitched collage from conked-out stuff.

"Be yourself - everyone else is already taken."

Celebrate Silent Film

Indulge- Travel, Adventure, & New Experiences

Haiku, Poems, Book Reviews & Film Reviews

The blog for Year 13 English students at Cromwell College.

John Self's Shelves

writer, editor

In which a teacher and family guy is still learning ... and writing about it

A Community of Writers

visionary author

3d | fine art | design | life inspiration

Craft tips for writers