Richard Thompson (© by jpbohannon 2018)

Richard Thompson (© by jpbohannon 2018)

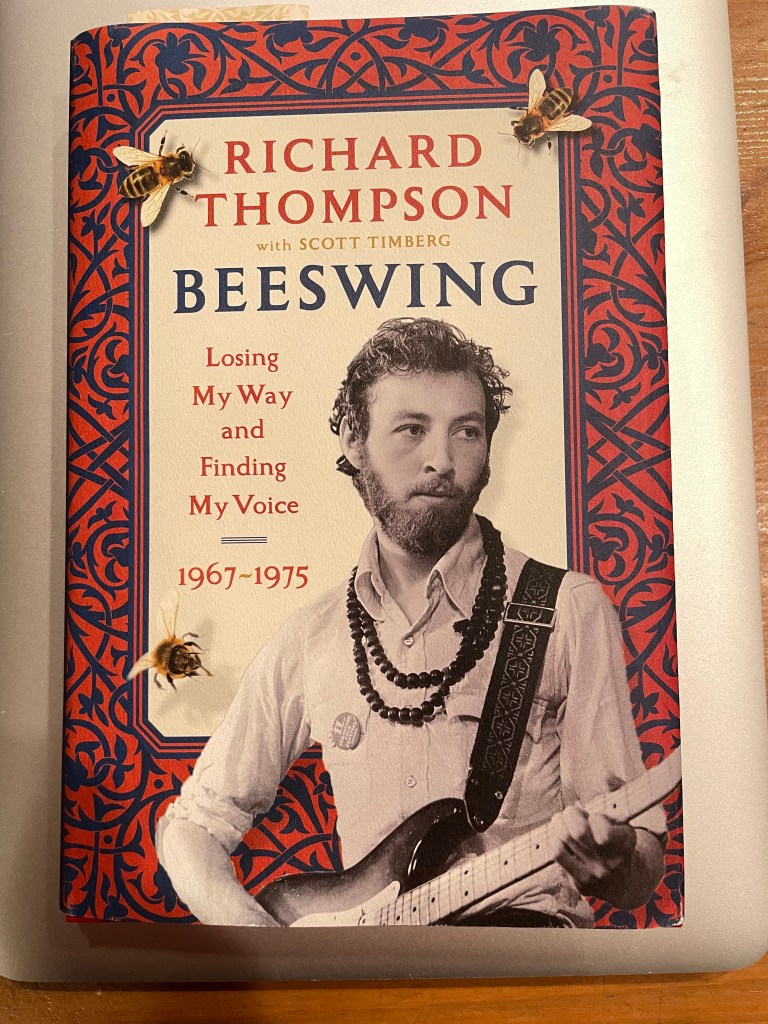

Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967-1975

Algonquin Books, 2001

At the beginning of the pandemic, in late March 2020, Bob Dylan released a near 17-minute song, “Murder Most Foul.” Among the many, various reviews, one of the most consistent comments was on Dylan’s encyclopedic knowledge of music. The song references scores and scores of songs, familiar and un.

Well, anyone who reads Richard Thompson’s new memoir of his formative years (1967-1975) will likely also be amazed at the range of music that Thompson cites as influences. From French jazz to American blues, from Highland traditional songs to African rhythms, from classical music to British music halls, Thompson seems to have absorbed it all and writes intelligently and knowledgeably about them.

From early on, Thompson and his mates seemed to have had a vision and knew what they, as Fairport Convention, wanted and did not want. They did not want to be like the earlier “British Invasion” bands that were exploring and copying American blues and R&B and often bringing that music back to America. They wanted to use native British themes and rhythms taken from centuries-old British traditions and meld it with rock-and-roll. And thus, Fairport Convention gave birth to what became known as British folk-rock.

While admittedly influenced by Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and other American singer-songwriters and American forms (Thompson claims that what The Band did for “Americana” music with Music from Big Pink was essential in confirming what they wanted to do with British traditional music), Fairport Convention took what it learned and applied it to British themes. For example Thompson took a 15th-century British poem, married it to a 19th century Appalachian tune and electrified it (“Matty Groves”). “Matty Groves” was one of five “reworked” traditional tunes–along with three originals–that appeared on the Liege and Lief album (1969), which is unarguably considered the beginning (and high point) of British folk rock. The claim that Fairport Convention “invented” the form can be appreciated by considering the bands later begun by former members: Pentangle, Frothingay, Steeleye Span.

But Beeswing is more than a musical history. If it were only about music, its appeal would be limited. Richard Thompson’s story is a testament of persistence, resilience and a search for peace, a cultural memoir of the zeitgeist of London and the music world in those frantic years. Its focus on music arises from the fact that after leaving school, Thompson never worked at anything else but as a working musician.

And his is a story that has an almost Shakespearean plot arc.

There is much tragedy: early on, when the band is on the rise and returning from a gig, their van goes off the road killing their driver/roadie, their drummer, and Thompson’s girlfriend. Thompson himself spent a good while in hospital. At another time, a truck missed a sharp turn and plowed through the second floor rooms where he and fiddle-player, David Swarbrick, were living. There were firings–how do you fire Sandy Denny, the greatest vocalist of the day–and there were leavings. Thompson left Fairport Convention to tour with his wife as Richard and Linda Thompson. And then there was the fiery divorce that colored their North American tour.

But there is also–not so much redemption, for he was no more lost than anyone else at that time–but a sense of achieved contentment, of understanding. Much of that is due to his discovery of Sufism, which for Thompson has a “nobility of being … it seem[s] like the way human being should be.”

photo © 2007 by Anthony Pepiton

Anyone who has seen Richard Thompson in the past 20 years know him to be a gentle, humorous, friendly performer. (He is, by the way, also considered one of the finest guitarists in the world. The L.A. Times calls him “the finest rock songwriter after Dylan” and “the best electric guitarist since Hendrix.” And anyone who has attempted to emulate his acoustic guitar playing is often quickly daunted.) Whether playing with the excellent musicians he surrounds himself with or performing solo, Thompson regularly puts on shows that always leave the audience with the feeling that they have just seen/heard something memorable and remarkable.

And it is this genial manner that one observes on stage that

informs the tone and pacing of his memoir.

Richard Thompson seems very much at peace with himself–perhaps this is where the “finding my voice” in the subtitle comes from–and this feeling of contentment permeates his memoir. Although Beeswing deals with a mere nine years–from the time he was 18 years old to when he was 27–they were nine years that helped form one of the trailblazers and icons of modern music.

Richard Thompson (© by jpbohannon 2018)

Richard Thompson (© by jpbohannon 2018)