“…even in an era of touchscreens and interactive spectacle, it’s human nature to feel awed and inspired in the presence of a giant rock.”

Robin Cembalest, Artnews. “The Gentle Giants of Rockefeller Center”

Robin Cembalest, Artnews. “The Gentle Giants of Rockefeller Center”

I woke today in one of those states. I didn’t know who I was or where I was or what I was supposed to be doing. And as I seeped into clearer consciousness, I felt in a rut…already in a rut at 4:45 a.m. Geeesh!

The day begins: the 57 bus, the Market-Frankford El, the R5 train and then a brisk walk, hoping for a co-worker to come driving by. I will do the reverse in the evening. And then again tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.

But the commute is not what was getting me. I enjoy it. I get plenty of reading done–and not a little dozing as well. But something wasn’t sitting well.

Simply, I am not sure what I am doing.

For work, I am teaching Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone, and Jim Shepherd’s Like You’d Understand Anyway. But I ask myself, “What am I teaching?” Sure they are great reads. They are more than that: they are thoughtful, engaging, and well-suited for introspection, reflection, and–hopefully–understanding. But, as for today…meh.

I know that it is a passing feeling, the not uncommon question of “Is that all there is?”

I know that it is a passing feeling, the not uncommon question of “Is that all there is?”

And I know I will get pumped by the next great book I encounter, by the old song that I hear from someone else’s radio, by a magnificent movie that comes in under the radar, by good craíc shared with friends.

But today the feeling is real. It is simply something you work through.

I was listening today to John Lennon’s “Watching the Wheels Go Round.” I was thinking beforehand that it reflected my own feelings today. But it was just the opposite.

Lennon is watching “the wheels go round” because he had gotten off the merry-go-round, had walked out of the maze, was no longer “playing the game.” He was enjoying the real things–his wife, his child, his new life.

But at the moment, for me (as for most of us), I need to stay on the merry-go-round as it continues to spin, mindlessly, pointlessly and without destination.

Nevertheless, today I am listening to what John says and that always seems hopeful.

My mother died yesterday.

She was a simple, quiet, sweet woman whose last few months were horrible. And while it might sound cold-hearted, I can honestly say she is better off today than she was the past few weeks. For better or worse, at least she is now at peace.

And while I have a good number of siblings and a large network of friends and relatives with whom to share the loss, privately I turn to Art with a capital “A.”

The picture above is of a painting by Pieter Brueghel. Entitled Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, it depicts the legendary fall of Icarus, who (in one story) famously disobeyed his inventive father and flew too close to the sun. The sun melted the wax holding together the wings that his father had fashioned, and he crashed into the sea. Through the ages, Icarus has become a two-sided symbol for artists: he is either a symbol of blatant disobedience akin to Eve or Pandora or Deidre or a symbol of great striving, of “flying to the sun,” of grabbing all the gusto one can. I usually lean to this second interpretation and see Icarus as an example of risking it all in pursuit of one’s dreams.

Anyway, this painting is one of my very favorites because

Brueghel has depicted this grand, mythic tragedy as happening amidst the pedestrian goings-on of daily life. If you look closely, you can see Icarus’ legs darting into the water in the right hand corner of the canvas. If you are not looking for them –and did not have the title of the painting to clue you toward Icarus–you might miss them entirely in the busyness of the entire painting. There is a shepherd, a ploughman, a single fisherman, a stately ship and a far-away city, but the boy falling out of the sky barely registers on their existence.

A very famous painting, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus also has been the subject of several poems, most notably by Auden and William Carlos Williams.

Below is W.H.Auden’s poem about the painting which now hangs in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Artes Belgique in Brussels:

Musée des Beaux Arts by W. H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

So yesterday, after the mortician took my mother’s body away, after my brother and sisters and I cleaned out her personal effects and donated her clothes to the needy, I drove away and stopped at a convenience store for a sandwich. The store was extra crowded, there was a particularly annoying man in line, and the cashier herself was particularly surly. I wanted to yell to them, to say, “Hey, don’t you know my mother just died?!” But of course I didn’t and of course they couldn’t have. They were simply going about their normal Saturday routines.

Instead I thought of Brueghel and Auden and Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.

Yet, Auden missed another part of the equation. While it is true that the world goes on despite, and during, moments of personal tragedy, it also does the same in moments of great personal triumph. We tend to think that much of this existence is about us, about our heartbreaks and our victories–and very little of it really is.

Anyway, my world is different today than it was yesterday. I must meet with siblings to arrange funeral services, arrange affairs at work for missed time, try to find a wearable suit for the funeral…and the entire time the great big world will go spinning along, unaware of what any of us are dealing with.

As Auden said, “they were never wrong,/The Old Masters.”

I had to get some work done on my knee this week and in order to do it, the doctors had to give me general anesthesia.

God I love it. It is the perfect vacation.

To start with, an anesthesiologist gave me a light anesthetic and then wheeled me into the operating room where I would be administered a more powerful anesthetic. I remember her wheeling me towards the operating room, I remember her saying to someone else that the bed had to be turned around because I had to go into the room head first.

And I remember nothing else. I awoke a little more than an hour later in the recovery room. How great is that!

For that short interim, I had no worries about bills, no stresses about work, no fretting about family, no anguish, no responsibilities, no obligations, nothing. I desired nothing, feared nothing, was attached to nothing. It is the very definition of Nirvana. And I experienced it without hours of meditation!

The word “nirvana” has been misrepresented by Westerners as a simple synonym for “paradise,” for an existence of pure pleasure and perfection. Nothing can be further from the truth. In Eastern thought, “nirvana” is the final stage of enlightenment, a state where there is NO pleasure and NO pain. One has NO desires nor regrets. There is no suffering, no joy, no self. One is completely separated from the pulls, the demands, the pains, joys, wants, and urges of modern existence.

Wow, that certainly sounds like the perfect vacation to me. Or a lethe-like morning of general anesthesia.

(Or at least until the painkillers wear off. Hah!)

A simple and wonderful book for westerners to read as an introduction to the Buddha,

to nirvana and the path towards it is Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha. It is a short, beautiful,

inspiring novel of Gotama Buddha, written by German author for the western mind.

One cannot finish the book without feeling some sense of peace. I used to give it out

quite often as a gift.

If you have never read it, try to find it. You can read it in one sitting.

If you have already read it, pick it up again. Those same good feelings will return.

When is it time to stop reading a novel? And why do I feel so guilty about it?

I decided today to go no further in Mark Leyner’s The Sugar Frosted Nutsack. Was it bad? No, it was quite entertaining? Was it difficult? No, not in the way say Joyce’s Finnegans Wake or DFW’s Infinite Jest is difficult.

To be truthful, it is simply a tiring read.

The title refers to poor Ike Karton, the “nutbag” as he is called in his neighborhood in Jersey City, New Jersey. Here is his introduction (35 pages in):

“What subculture is evinced by Ike‘s clothes and his shtick, by the non-Semitic contours of his nose and his dick, by the feral fatalism of all his looney tics–like the petit-mal fluttering of his long-lashed lids and the Mussolini torticollis of his Schick-nicked neck, and the staring and the glaring and the daring and the hectoring, and the tapping on the table with his aluminum wedding ring, as he hums those tunes from his childhood albums and, after a spasm of Keith Moon air-drums, returns to his lewd mandala of Italian breadcrumbs?

So begins the story of Ike Karton, a story variously called throughout history Ike‘s Agony, T.G.I.F. (Ten Gods I’d Fuck), and The Sugar Frosted Nutsack. This is a story that’s been told, how many times? –over and over and over again, …”

Ike is a believer in a pantheon of Gods who have played havoc with the universe for billions of years. Earlier we learn that

The Sugar Frosted Nutsack is the story of a man, a mortal, an unemployed butcher, in fact, who lives in Jersey City, New Jersey, in a two-story brick house that is approximately twenty feet tall. This man is the hero IKE KARTON. The epic ends with Ike’s violent death. If only Ike had used for his defense “silence, exile, and cunning.” But that isn’t Ike. Ike is the Warlord of his Stoop. Ike is a man who is “singled out.” A man marked by fate. A man of Gods, attuned to the Gods. A man anathematized by his neighbors. A man beloved by La Felina and Fast-Cooking Ali, and a man whose mind is ineradicably inscribed by XOXO. [these are the names of gods we’ve already met]. Ike’s brain is riddled with the tiny, meticulous longhand of the mind-fucking God XOXO, whose very name bespeaks life’s irreconcilable conntradictions, symbolizing both love (hugs and kisses) and war (the diagramming of football plays).

Are you tired yet? I am…(but I have such a developed sense of guilt that I will probably return to it before the evening’s out.)

The novel begins with the beginnings of the universe. This gaggle of gods arrive on a school-bus, blaring the Mister Softee jingle, like a bunch of college students “Gone Wild” on spring break. Like the gods of other mythologies, they are petty and mischievous and promiscuous and quite often harmful to humanity. Now, they are living in the tallest (and most opulent) building in the world (now they are in Dubai, but they have had to move several times as humans keep building taller buildings.) Bored and propelled by their own machinations and relations they have become obsessed with Ike Kantor.

The novel plays with meta-fiction to a large degree. A sentence is repeated. Then the sentence that makes the repetition is repeated again including the original sentence. And again. And again. It is tiring…and soon loses its cleverness.

But the book is not the theme of this post; it is is the decision to give up on one. Why do some people (myself to be sure) feel a sense of obligation to finish a book once he or she has begun it? Is it financial, in that you’ve invested fifteen bucks in a book you might as well get your money’s worth? I don’t think so.

Is it something that happened to us when we were school children? Are we afraid that the nuns, headmasters, schoolmarms are going to rap our knuckles with a ruler for not completing our assignment?

Or is it respect for the artist? Do we feel the need to stick with something, to see where it leads to, out of respect and admiration for the writer’s work?

I don’t know.

But I have a day and half free–so I’ll probably end up finishing it anyway.

I went to see a band tonight down at a local pub, The Dark Horse, known more for soccer clubs and televised soccer games than for music. But some friends of mine are in this band and I had to see them.

I have played with two of the members before in an Irish band, but this new band, The Flashbacks, is just that …a flashback to several decades earlier. The band started out as a Beatles cover band, but then expanded with a lot of Steely Dan, Yardbirds, Stones, Kinks, before settling into CSNY, Beach Boys, the Dead, Eagles, etc. (They tout themselves as the second British Invasion, but they cover a fair amount of American bands as well.)

And the reason they can cover this music is that they are DAMN GOOD! The harmonies are precise–three-part most of the time–and the musicianship is impeccable. They are seasoned players who have, for the most part, known each other for a very long time and they play to each others’ strengths and build on it. The youngest member–Joe Manning–is just a pup compared to the others, (he wasn’t born when these guys first started playing together) but he is one of those wunderkinder who can play anything and play it with perfect beauty, wit and definition. If he had been alive forty-five years ago, they would have called him a god.

And so this got me to thinking….

There are an awful lot of very talented people out there. I could go see scores of really talented bands or individuals every night of the week in my city alone. Multiply that by every other city, burg, town. How many great musicians are there in Dublin? Edinburgh? Berlin? London? Madrid? Cairo? Innumerable.

I know very talented artists, amazing writers, magical poets, extraordinary designers who day in and day out work at their craft (or because of the ways of the world, work at their “day-job” and then work at their craft) and create wonderful pieces. I am sure you know similar people in your parts of the world. What separates these artists from those who’ve become household names?

Luck, certainly plays a role, but a very minimum one. Being at the right place at the right time, meeting someone who can truly help, etc. are all fortunate but are not the thing that separates the very good from the great. And mere technique is not sufficient–there are thousands of technically gifted people.

I believe it is focus, focus on one’s calling at the expense of all else.

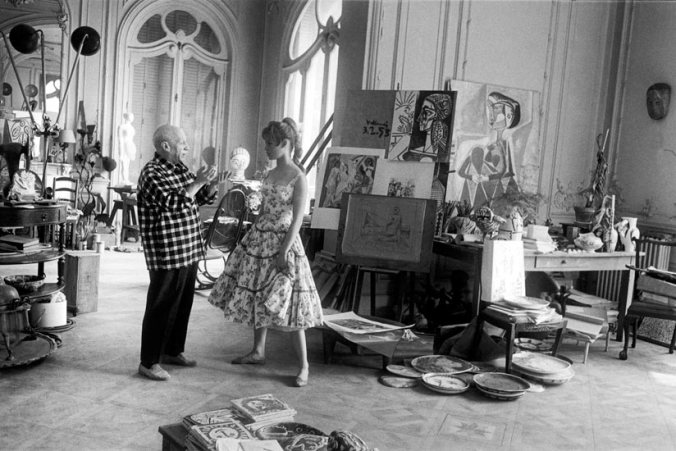

Picasso and Bardot. How great is that?

re-posted from http://weekendspast.com

I remember having a discussion with my father once. He was bemoaning the way that Picasso treated women, discarding them indiscriminately whenever it suited him. I argued that it was a symptom of his genius. (He challenged my assumption that Picasso was a genius.) Genius, I said, uses everything it comes across. There is nothing else that matters but his or her art, his or her genius–other people and other people’s emotions included.

The conversation came up again this week, when someone remarked on seeing the television movie Hemingway and Gellhorn on what an unlikeable cad Hemingway actually was. Again, it is all ego wrapped around his art…or maybe the opposite, all his art is wrapped around his ego.

The attitude can be summed up in the clichéd saying “It’s his (her) world, we’re just living in it.”

Who else has stepped on everyone to further their art–or in the furtherance of their art? We could cite both Shelley and Byron, who stepped on and used everyone in their belief in their own genius and the entitlements it should deserve.

But this is not only in the arts. Steve Jobs may have been a genius but he was hardly a likeable person. And Bobby Fischer, arguably the greatest chess player ever, became more than simply an egocentric genius. He became a misanthropic, hate monger.

Mozart–a man who could create entire operas in his head without touching an instrument–was certainly egocentric, almost to an infantile degree.

So what about all your acquaintances who are truly talented, gifted people? Is it that they are decent human beings whose company you enjoy, whose interest in you and others around them is obvious, that keeps them from reaching the pantheon of genius.

And would you have it any other way? I know I wouldn’t! I too much enjoy the people who are creating wonderful, beautiful things–like the middle-aged Flashbacks at The Dark Horse pub–and who are still wonderful human beings, interested in the world and the people around them.

The etymology of the word “amateur” comes from the word Latin word “amat” –to love. Whether one is paid or nor, celebrated or not, it is the love of doing, making, performing something that is good and beautiful that makes for a better world.

I’ll go see the Flashbacks, the next time they play!

I have been sick for the past five days. Sick enough that I have come home from work every night and gone straight to bed. Sick enough that I am existing on juice, tea, aspirin and kleenex. Sick enough.

This morning I said to someone “I don’t even want to be inside this body anymore.” Not really sure what that meant, but it got me thinking. Who was talking there? Who is this “I” that feels itself a guest inside this “body”? Of course, I couldn’t let it go from there.

I had to look for answers.

The questions are hardly new: ancient Greeks and the early Hindu yogis each grappled with the Mind-Body Problem. In the modern world, it was Descartes on one side and Spinoza on the other side of what became contrasting points of view. Descartes and the Dualists believed, in essence, that the mind and the body were separate entities. This seems to jibe with the Yeatsian view in yesterday’s post that something existed apart and before the body was made. Of course, as philosophers are wont to do, the Dualists have splintered into various groups as well.

Spinoza and the Monoists believe that the mind and the body are one. Our feeling that these two entities are distinct is simply the properties and emanations of the brain. With recent advances in neuroscience, brain-mapping, psychology, etc., it appears that the mononist position has been gaining strength. Yet it too has broken into several splinterings. The most basic is that between reductive and non-reductive. The reductive believe that ultimately all mentality, all mindfulness, will be able to be explained through a scientific understanding of our physicality. The non-reductive agree that all there is to the mind is the brain and its functions, but believe that its functions cannot be “reduced” to the parameters and terms of physical science.

So all of this is scary stuff. What does it mean if our “self” is really just a creation of the physical firings and synapses of our brain in conjunction with the countless other functions going off –or awry–in our body each moment. If our “self” is truly just a construct of our brain, then that construct can be manipulated. Don’t think so? Advertisers, politicians, behaviorists do! It is, after all, their job to make you do, buy, think, act in a way that you did not necessarily consider before. Their livelihoods are predicated on your “self” being manipulated.

I know that at the moment my own body is misfiring–sinuses are clogged, limbs are achy, head is pounding, throat is soar, lungs are tender. Yet who is “the self” that is getting fed-up at that body, fed-up at the slow pace of recovery. It would seem that I am dealing with dualism here. And yet, intellectually I side with the monoists.

I guess, my little old brain has simply been formed in a way that tends to have these thoughts while my body hits these speed-bumps. It’s all part of the package.

“The Yale philosopher Shelly Kagan … manages to raise some interesting and subtle concerns about …notions relating to the question of what’s really bad about death, including this one: Why do we regard no longer existing (post-mortem nonexistence) as worse than not having existed before our births (prenatal nonexistence)? And are we wrong to do so?”

“The Opinionator,” New York Times, May 16, 2012.

I love this question. I have thought of it before, and it gives me comfort. For it makes perfect sense to me. I wonder if Mr. Kagan is aware of the Yeats’ poem, “Before the World was Made.” I would imagine he is. I know I thought of it right away when I read the article.

Before the World was Made

If I make the lashes dark

And the eyes more bright

And the lips more scarlet,

Or ask if all be right

From mirror after mirror,

No vanity’s displayed:

I’m looking for the face I had

Before the world was made.

What if I look upon a man

As though on my beloved,

And my blood be cold the while

And my heart unmoved?

Why should he think me cruel

Or that he is betrayed?

I’d have him love the thing that was

Before the world was made.

For here, Yeats too is looking at what Kagan calls “prenatal nonexistence”–though Yeats prefers to think of it as “prenatal existence.”

Now Yeats is working in a spiritual cosmology quite different from that which the Yale philosopher is dealing with. Yeats was always susceptible to spirituality and spiritualism…mysticism and the occult. (Adrienne Rich famously called him a “table-rattling fascist.” Click here for Evan Boland’s essays on literary antagonisms.) Nevertheless, he was very much interested in concepts of a soul. He believed–through a complicated mythology of his own making, explicated in his book The Vision–in an individual, social, and civilization-wide reincarnation or continuance of the soul. And so through this series of Yeatsian cycles we have it: a “pre-natal” AND “post-mortem” existence, as the philosopher says.

And yet, there is also something else going on in the poem that is not as deep, not as cosmic, not as “philosophical.” This is not a cosmic dance taking place in front of the mirror. It is that old familiar dance of seduction and romance. For who is the speaker sitting in front of her vanity? Has Yeats returned to musings on his old beloved Maude Gonne? Is he thinking of her daughter–to whom he once proposed having been rejected for the umpteenth time by Gonne? The poem was published in 1933 when Yeats was 68 years old. The following year Yeats had the Steinach operation performed–a procedure of inserting animal glands into the body in order to increase testosterone production. Good old Yeats–he was now 68–was not giving up on this existence…and at this time was carrying on several romantic affairs with much younger women.

The poem itself appeared in the collection, The Winding Stair, and was one of twelve poems included in a section called “A Woman Young and Old.” If the speaker is a woman where does she fit in that continuum? Is this a young woman relatively new at the game? Or a more experienced woman, who could look on any man “as though on my beloved”?

And what is it she would have him love? What existed “before the world was made”? For the philosopher Kagan, the answer is nothing. For Yeats it is something large, something essential.

◊

As an aside, I knew that Van Morrison had recorded a song version of the poem. I also knew that Mike Scott and the Waterboys had just put out an album, An Appointment with Mr. Yeats, on which the poem appeard. But I just learned that Carla Bruni–the former first lady of France–had also recorded the song. I don’t know why, but I find that amusing. Anyway, here’s Van the Man’s performance of Yeats’ “Before the World Was Made.”

I am reading a book, The Night Swimmer by Matt Bondurant, where early in the novel, a young, successful couple have these yearnings to chuck it all and to move to Ireland. They are intelligent and aware of the commonness of this trope–they intentionally nickname their street “Revolutionary Road” after the Richard Yates’ novel. Earlier, before the dream of starting afresh in Ireland, the couple had wished to live in the time period when the novel Revolutionary Road takes place–a Cheever-esque world where pitchers of martinis and pyramids of cigarettes punctuated each evening. That glamorous “Mad-Men” world had not work out for them, but the dream of emigrating does: the husband wins a pub in County Cork, Ireland. Needless to say, the paradise/excitement/vigor of the new life they imagined in this other world does not pan out they way it had in their dreams. And like in Richard Yates’ novel, the marriage suffers more than greatly.

What is it about us that makes us often wish we were in some other place, some other time? In Midnight in Paris, Woody Allen wrestles with this question. The protagonist wishes he lived in 1920s Paris, but the 1920s woman he meets wishes she lived in the Paris of the 1890s? And in fact, the life he is already experiencing in 2011 turns out to be full of promise. Why is this nostalgia for a world other than our own, for an imagined place and an imagined time, so strong? Is it general among everyone? Or only with a certain type of person?

I walked out to get a coffee today and on my walk home I cut down an alley. Looking around me, I realized that I could have been walking in any foreign city with any foreign  adventure around the corner. I could have been in Paris, in Cork, but I was merely a short stroll from my own house. I took a picture with my phone. The concept of a more exotic, romantic other place is just a whiff of smoke–it is always around us if we keep our eyes open.

adventure around the corner. I could have been in Paris, in Cork, but I was merely a short stroll from my own house. I took a picture with my phone. The concept of a more exotic, romantic other place is just a whiff of smoke–it is always around us if we keep our eyes open.

Now it is often said that one doesn’t appreciated one’s home until one is separated from it. Joyce gave us a loving, photographic picture of Dublin, but only when he was writing in Switzerland and Paris. Beckett too gives us an unnamed but undoubtedly Irish landscape in his novels and several of his plays and he too was across the sea. But that is different than romanticizing a place one wishes for, a place that does not exist. What Joyce and Beckett do is understand what they had left, see it without the distortion of being so close within. This is not the same as dream-manufacturing, as imagining a better world through the kaleidoscope of nostalgia and generalities.

Nevertheless, there are still many days when I wish I was somewhere else, when I don’t appreciate the vitality of the world around me. But in these daydreams, it seems that I am never working, that there is no concern about putting food on the table or where the next dollar is coming from–who wouldn’t find that attractive. And that’s what makes it all somewhat of a sham.

Bertrand Russell once said that people would do almost anything to avoid having to think. And we do. Consider how we go through most of our days. Rise, commute, work, commute, dine, sleep. Certainly there are vacillating degrees of how purposefully we interact with our own lives, but mostly, I would say, we do things by rote. For the most part, the majority of us do not “live our lives deliberately” as Thoreau advised us to–we would make ourselves mad if we did–but what are we sacrificing?

Bertrand Russell once said that people would do almost anything to avoid having to think. And we do. Consider how we go through most of our days. Rise, commute, work, commute, dine, sleep. Certainly there are vacillating degrees of how purposefully we interact with our own lives, but mostly, I would say, we do things by rote. For the most part, the majority of us do not “live our lives deliberately” as Thoreau advised us to–we would make ourselves mad if we did–but what are we sacrificing?

Samuel Beckett wrote that the routine, the habit, the treadmill of our lives is a way of deadening the pain of existence (how wonderfully Beckettian!); breaking out of the routine, the habit, the treadmill is exciting and might mask the pain, but it is temporary and not without risks. To think deliberately is indeed difficult. But it is what makes us who we are. Our thinking is what separates us from others, what individualizes us. There is a second kind of truth in the Cartesian “I think therefore I am.” It is not simply a statement of existence, but one of uniqueness as well, an emphasis on the “I.” And if we choose not to think, are we waiving our individuality to become simply a part of the herd?

In politics, for example, do we think or do we react? Do we consider the world around us or do we merely accept what we have been trained to accept? Are we so entrenched in our “camps” that we allow their ideas to immediately become ours without the trouble of thinking? Do we even have a personal philosophy? How many of us could state what it is? What do we believe in? When have we last THOUGHT about what we believe?

The avoidance of thinking is hardly a 21st-century phenomenon–it just seems easier to do these days. The opportunities for distraction, the ease in which we can fill our lives with noise, makes it all too easy to avoid stopping to think. And like most habits, once we have learned to “not think,” it becomes a very hard habit to break.

But again, what are we sacrificing?

I’m not sure, but I’ll think about it.

The Official Web Site of LeAnn Skeen

Grumpy younger old man casts jaded eye on whipper snappers

"Here is my secret. It is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.."- Antoine de Saint Exupéry

Of writing and reading

Photography from Northern Ontario

Musings on poetry, language, perception, numbers, food, and anything else that slips through the cracks.

philo poétique de G à L I B E R

Hand-stitched collage from conked-out stuff.

"Be yourself - everyone else is already taken."

Celebrate Silent Film

Indulge- Travel, Adventure, & New Experiences

Haiku, Poems, Book Reviews & Film Reviews

The blog for Year 13 English students at Cromwell College.

John Self's Shelves

writer, editor

In which a teacher and family guy is still learning ... and writing about it

A Community of Writers

visionary author

3d | fine art | design | life inspiration

Craft tips for writers