Last week, at a “workshop/institute/conference” I am attending for a few weeks this summer, Christian Talbot spoke to us about “chaos theory” and the creative need for tension in any collaboration. The theory goes, simply, that any collaboration must begin with chaos. Butting against each other is a conflict of ideas–and often a conflict of personalities. As the collaborative project goes forward, this tangle of conflicts begins to stretch out into a diametric pattern of varying depths with one single thrust being countered by another until ultimately the collaborators move directly towards the goal. Talbot insisted that the initial conflict is essential, even positing that if there is no conflict the final outcome can not be as robust as it possibly could have been.

The man next to me, Emanuel DelPizzo–an excellent musician and leader of a twelve piece R&B band–cited the Beatles as evidence of this tension. He cited the arguing and fighting and one-up-manship that often went on during a Beatles’ recording session and the perfection of the result. We both talked about the tensions that can arise within bands and the trust that one ultimately has to place in one’s fellow players.

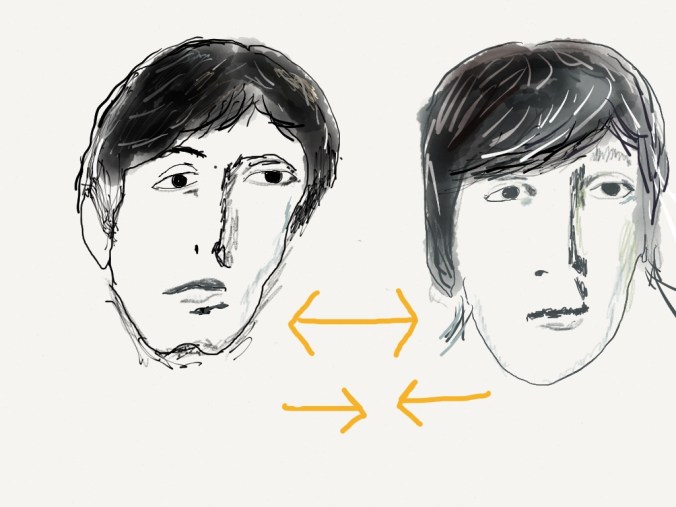

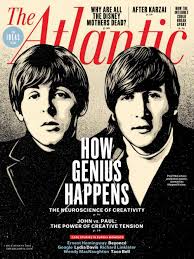

And then, this coincidence ensued. The following day, as we were moving from one task to the next, I walked over to a quiet part of the room where there were a pile of recent magazines. On the top was a copy of the July/August issue of The Atlantic. A picture of Lennon and McCartney on the cover caught my eye. It is The Atlantic’s “IDEA issue.” (Though I would think it would want all its issues to be “idea issues”!) Anyway, the essay was touted on the front cover as–“John vs. Paul: The Power of Creative Tension.” This is exactly what Christian was talking about yesterday and was the very example that Manny had offered.

And then, this coincidence ensued. The following day, as we were moving from one task to the next, I walked over to a quiet part of the room where there were a pile of recent magazines. On the top was a copy of the July/August issue of The Atlantic. A picture of Lennon and McCartney on the cover caught my eye. It is The Atlantic’s “IDEA issue.” (Though I would think it would want all its issues to be “idea issues”!) Anyway, the essay was touted on the front cover as–“John vs. Paul: The Power of Creative Tension.” This is exactly what Christian was talking about yesterday and was the very example that Manny had offered.

The essay by Joshua Wolf Shenk is entitled “The Power of Two” and immediately attempts to diffuse the prevalent idea, that Lennon wrote his songs and McCartney wrote his. Debunking the idea of the solitary genius–so prevalent in popular lore and imagination–Shenk states that the two very different friends bounced off and into each other in order to create what they did.

And the two were in fact very different. Shenk quotes Lennon’s first wife, Cynthia, who said, “John needed Paul’s attention to detail and persistence, and Paul needed John’s anarchic, lateral thinking” (p. 79). And this symbiosis continued to fuel their creativity. (One could seriously argue that nothing they wrote separately afterwards attains the same level as their “collaborative” effort.) I was surprised to hear that McCartney, more sure of himself, was the one likely to take criticism badly, while Lennon was more open to others’ opinions and more amenable to change. Shenk attributes this to McCartney’s perfectionism.

Shenk cites Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the White Album as an example of the collaborative conflict that the two would cycle through–both jockeying for dominance, both vacillating between the alpha male and the diplomat. Sgt. Pepper’s showed the two working closely together. For example, they volleyed Lewis Carroll-like phrases back and forth to each other to write “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and they simply fused two separate songs together to create the masterpiece “A Day in the Life.” Lennon called the White Album, “the tension album,” but as Shenk writes:

“Despite the tension–because of the tension–the work was magnificent. Though the White Album recording sessions

were often tense and unpleasant ([EMI engineer Geoff] Emerick disliked them so much that he flat-out quit),

they yielded an album that is among the best in music history.” (p. 85)

And when they did write separately they egged each other on. Lennon scoffed at MccCartney’s original opening of “I Saw Her Standing There” and fixed it. McCartney softened the raw pain of John’s original version of “Help,” adding a counter-melody and harmony. And even when they were apart, they were bouncing off each other. John wrote “Strawberry Fields” –about a nostalgic spot of his boyhood Liverpool–in late 1966 and the band recorded it on December 22 of that year. Seven days later McCartney arrived with a song he had written about another iconic Liverpool spot, Penny Lane. Shenk quotes McCartney saying that John and he often played this answer and call type of thing–sort of the middle ground of that chaos theory illustration.

Any one who knows the story of The Beatles, knows roughly the story of their falling out and “disbanding.” And yet, Shenk returns to the final concert–the rooftop performance on top of Apple Studios–and sees the old collaboration–both the conflict and the trust–still evident. Standing in the positions that they had taken in the early days, the two rely on and trust each other, even through some miscues and misstakes, to present a concert that was both memorable and historic.

While it is fun, to travel through the Lennon and McCartney’s creative process–and through their times in the studio–this is not really the focus of Shenk’s article. He is attempting to show the workings of creative pairs. He lists creative pairs from Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ralph Abernathy to Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Shenk enumerates McCartney and Lennon’s differences and their tensions as well as their friendship and trust as being the forge in which their art was struck. As Shenk states:

John and Paul were so obviously more creative as a pair than as individuals,

even if at times they appeared to work in opposition to each other. …The essence

of their achievements, it turns out , was relational. (p.79)

And that achievement is timeless.

Shenk, Joshua Wolf. “The Power of Two” The Atlantic. (July/August 2014, pp. 76-86)