I have been going through a noticeable streak of coincidences lately. In a particular ten days to two weeks, I will repeatedly see, hear, read about something that I hadn’t noticed or thought of in a long time. It might be a friend who has moved away…a movie I hadn’t seen in decades…a book that I had forgotten that suddenly is being cited everywhere.

Anyway, this week it has been Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. I knew who Keaton was, had always preferred Chaplin, but respected his enormous role in the history of movies. I knew little about Lloyd except for his famous clock scene.

And now Keaton seems to be everywhere. I wonder if, like so many things in modern culture, it is simply Keaton’s turn to be the object contemporary interest. (Contemporary interest has a very short life and while it might be Keaton in 2012, the focus could as easily turn to Jacques Tati for 2013, or Mack Sennett by July.) Who knows when it will be Lloyd’s turn?

Film connoisseurs have long praised Keaton. Orson Welles called his The General “the greatest comedy ever made…and perhaps the greatest film every made.” And Roger Ebert called Keaton “arguably the greatest actor-director in the history of movies.” Lloyd’s reputation is not as high-flying. Part of this came from Lloyd’s demanding such a prohibitive price for television broadcast of his films–and so his work is generally less known than either Chaplin or Keaton.

One of his most famous scenes is this:

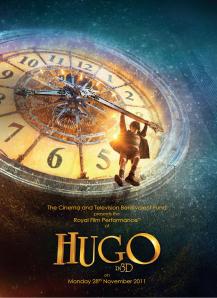

Indeed this scene is very obviously alluded to in the 2011 film Hugo, based on the Brian Selznik book The Invention of Hugo Cabret.

In the story, the young boy Hugo lives in the clock tower of a Parisian train station in the 1930s. During the course of the film, he sneaks his new friend Isabelle into a movie house. She has never seen a motion picture before and the film they watch is Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last! with its famous “hanging from the clock” scene.

In the story, the young boy Hugo lives in the clock tower of a Parisian train station in the 1930s. During the course of the film, he sneaks his new friend Isabelle into a movie house. She has never seen a motion picture before and the film they watch is Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last! with its famous “hanging from the clock” scene.

Later on, young Hugo himself must escape some danger by hanging from the clock hands and moving along to safety. In a story that is basically about the birth of cinema, the nod to Lloyd’s iconic clock scene is both appropriate and deserved.

A photo of Lloyd hanging from the clock is in the book. And the film clip is shown in the movie.

And this is where the coincidences really start!

On Friday, I am in a coffee shop, minding my business and reading the novel The Wonder Boys by Michael Chabon. Two guys in the table next to me are having a friendly argument and the argument is about Harold Lloyd’s hanging from the sprung clock. The one guy is insisting that the actor is Buster Keaton; the other insists it is Harold Lloyd. I am especially proud of myself for not inserting myself into the discussion–as is often my wont.

Yet it goes further. About an hour later, I am still reading and I come to a passage in the novel where the narrator introduces one of his writing students to his wife who has left him the day before and who he–and the student–have followed to her parents’ house, in a slap-stick sort of way that would have made these early film directors proud.

“This is James Leer. From workshop.”…

“This is James Leer. From workshop.”…

“The movie man,” she said. “I’ve heard about you.”

“I’ve heard about you, too,” said James.

I thought for a moment that she might ask him about Buster Keaton, one of her idols. but she didn’t.

Did I just read that right? “I thought…she might ask him about Buster Keaton“? Okay, simple coincidence. An hour after overhearing the Lloyd/Keaton conversation, but a simple coincidence.

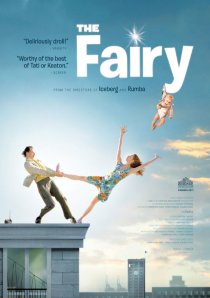

So it is Tuesday, and exams are over, and I am getting out of work around 11:15. I check to see what is playing, because I particularly love going to the movies when rest of the world is at work. There is a film called The Fairy (le fee) with an enchanting poster that I know nothing about. I go online to read what it is about. Here’s what they say to begin with:

The Belgian-based trio of Dominque Abel, Fiona Gordon and Bruno Romy (The Iceberg) write, direct and perform absurdist comedies in the tradition of Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati. The Fairy is a candy-colored romp set in Le Havre—a non-stop string of hilarious sight gags and madcap chases.

More Keaton. It’s as if he’s following me…or I unconsciously am following him. Even the movie poster alludes to its Keatonesque qualities.

So I am off to see The Fairy this afternoon. Off to see slapstick and physical humor from this Belgian trio, but I hope that it rises above that. The slapstick of Keaton and Lloyd and Chaplin, as well, was always more than pratfalls. It always said something true about the human heart. Something important about all of us.