Art

A Portrait of the Artist with One Left Foot

I’ve had the nice experience of putting two seemingly different works together and seeing startling comparisons that I hadn’t thought of before. In the class I am teaching on Irish Literature, we had begun the semester with Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. From there we moved through some Frank O’Connor stories, some Yeats poems, and three plays by John Millington Synge. And then as a breather, I showed the film My Left Foot, based on the autobiography of the Dublin poet, painter and writer, Christy Brown.

I have a fond relationship with My Left Foot which began long before the film was released. A friend of mine was living in San Francisco, working as a nurse. She would search the used book shops looking for the odd nugget, and she was always very kind to me. Every so often there would be a T-shirt from some cleverly-named dive bar, an esoteric album that no one knew about it, or a used book she found in her travels. One day, in the mail came a package containing My Left Foot by Christy Brown. I didn’t know the book at the time though it was twenty years old by then, but the worn and ragged dust jacket and the beaming face of Christy Brown on the back announced the joy, the vibrancy, the humor, and the pathos of the story inside.

I remember reading it twice in a short space of time, of lending it to a friend, and then lending it to another, and soon I lost track of it. And, to be truthful, I forgot about it. Until the movie was released and Daniel Day-Lewis’s performance announced to the world that this was someone to watch.

Viewing it this past week, so close to having finished Joyce’s Portrait, however, impressed on me how similar the story of these two Irish artists are. Joyce’s hero–Stephen Dedalus–is a sensitive, young child, bullied a bit at school, helpless without his glasses.

That Christy is also helpless, everyone assumes. Born with cerebral palsy and able to move only his left leg, he spends his early years lying under the stairs watching his family interact with each other—for better or worse. Joyce’s novel also begins with the early interactions of the family. From the hairy face of his father and the nicer smell of his mother when he was an infant to the fierce political/religious argument at Christmas Dinner, the Daedalus family is indeed similar to the Brown family. Particularly in the characterization of the fathers and mothers.

Simon Dedalus and Paddy Brown are hard men, perhaps a bit too fond of the drink. And both young boys, Christy and Stephen, see it as their responsibility to save their families from the fathers’ excesses. The mothers are doting: Christy’s mother innately sure that her son was more than just the vegetable that everyone believed him to be and Dedalus’ mother praying for her son’s soul and protecting him from his father’s increasing wrath.

And it wouldn’t be an Irish tale, if religion didn’t play a part. Father Arnall’s sermon on hell affects Stephen to such a large degree that he believes he might have a priestly vocation. And Christy is taught religion by a priest who comes to the house and who is also fond of describing the fires of hell–and causing young Christy no end of terrors.

Relations with the opposite sex are a stumbling block in both works as well. Sensitive Stephen vacillates from madonna to whore to madonna throughout, while Christy–caged within his crippled body–falls in love easily and is rebuked as often.

But the importance of both works is the creation of the Artist. Joyce’s Dedalus ultimately abandons church, nation and family in order to strike out on his own and “forge …the consciousness of [his] race,” while Christy embraces that world–dear dirty old Dublin and his sprawling family–to find the inspiration of his art. The artistic output–however disparate–is not the point here. The point is the development of an artist within similar constraints and backgrounds, a tale of two young men who travel the same narrative arc in order to discover the art that is within them.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

To one and all, Happy St. Patrick’s Day.

Do What You Love: The Philadelphia Museum of Art Craft Show

On Friday past, I went to the Philadelphia Art Museum’s annual Craft Show. Now this isn’t your usual craft show with knitted tea cozies, outré Christmas decorations, and cute tchotchkes for the home. This is major art. The exhibitors were potters and metal workers, fabric artists and glass blowers, painters, fashion designers and jewelers, woodworkers and stone carvers. This was some major stuff–and more often than not far above my price range.

Yet it was all beautiful. At one point, I called over one of the women I was with to see these magnificent glass platters. The artist corrected me: what I thought was glass was actually wood. All his pieces were wood. Yet they were so translucent and brilliant and delicate that one would never first believe that they were wood.

Two fashion designers–at opposite ends of the “elegance” scale–were both kicky and inventive. Their dresses and capes and skirts and pants were flowing with ruched materials or angular draping. One woman painted gorgeous canvasses, part abstract/part folk art, and treated them so they could be use as floor coverings. Runners for hallways, area mats for large rooms. They were exquisite.

There was exquisite furniture and graceful pots, jewelry both elegant and extreme. There was a perpetual motion glass wine aerator and eyeglasses made of wood. There were graceful ceramics and fun metal sculptures. There was simply aisle after aisle in the cavernous Convention Center filled with magnificent works of human artistry.

And that was the true beauty of this collection. Hundreds of people from around the world were simply doing what they loved–creating things of beauty. How lucky one must be to be able to do what he or she loves as not their job but as their vocation, to be able to start the day with nothing and end up with something. For the artist does not go to work, he is always at work. He eats and sleeps and breathes his work. And while not all of these crafts were to my taste–though many, many were–all were to my liking. For something inside me loves the idea that human beings are a species that does create, and often creates piece not for their utility but for their simple and utter beauty.

The house that Barnes built…now relocated

Yesterday I went to the new home of the Barnes Collection. The building is light and airy and relaxing and peaceful. And the art there is second to none. Even to the least knowledgeable visitor, there must be ten paintings in each room that are recognizable. In many ways, it is like walking into a primer of Modern Art.

To give you some idea of the scope of this collection, it holds 181 Renoirs, 69 Cezannes, 59 Matisses, 46 Picassos, 16 Modiglianis, 11 Degas, 7 Van Goghs, 6 Seurats, as well as numerous works by Manet, Utrillo, Demuth, Prendergast, de Chirico, Gauguin. And shoring up these masters is the odd El Greco, Rubens, or Titian. There is also a large array of African sculptures, modernist textiles, ceramics, American folk art, Pennsylvania-Dutch cabinetry, and a large assembly of ironwork that, like the delicate chain of a rosary, seems to link the paintings together in each room.

And all in a private collection!

There are so many stories behind the Barnes Foundation. Having amassed what is arguably the most famous personal collection of modern art in the world, Albert C. Barnes had willed that his collection remain at his residence in Merion, a suburb of Philadelphia. He had stipulated that the collection would be open to the public for no more than two hours a week and that reservations had to be made two-weeks in advance. He wanted the works to be used solely by artists, students and educators for study, and so the paintings were not to be loaned or reproduced. After what would be the first of many legal challenges, these stipulations were first amended to two-and-a-half hours a week and visitors were limited to 500 people a week.

(Originally, Barnes wanted his collection for art students and laborers only, and he had little time for the rich and celebrated. In a room outside the galleries, there are documents from Barnes’ life. One is a letter to the automobile tycoon, William Chrysler, stating that he must refuse his request to visit the collection because at the moment he is practicing goldfish swallowing and can not be bothered! Another form was a bill of sale for eight Picasso’s. He had spent $1490.00)

In 1992, the Barnes Foundation was in some straits, the house itself needed some repair, and after a great deal of legal wrangling much of the collection went on a world tour. For the first time, the collection, which had been so limited in the numbers of people who had actually seen it, was now being viewed by millions in cities around the world.

But the tour still did not bring in enough funds. When the foundation tried to extend its hours, the local municipal government balked, and after several years of suits and counter-suits, of bitter and arcane legal wrangling, it was decided that the collection would be moved to a new location on Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The move was (and still is) highly controversial and was the subject of the 2009 documentary, The Art of the Steal.

But to be honest, the museum is beautiful.

The new location recreates the rooms of Barnes’ home to the finest detail–baseboards the exact height, wall paper the exact texture, paneling the exact wood–and encases them in a building that is peaceful, modern, and relaxing. And the bonus is that now so many more people are now able to see what was before limited to such small numbers.

How impressive is Barnes’ collection? It literally takes one’s breath away–you walk into the first room and you gasp! The sheer number is overwhelming. Above the windows of the first room are the three large panels of Matisse’s Dancers. You are in a room with several Picasso’s and yet that is not where your eyes go immediately.

The paintings are hung with precision and deliberation–two small Renoir landscapes will surround a large Renoir portrait which will contrast with the Matisse portrait above it. And the ornamental ironwork that is placed throughout reflects the patterns, shapes and themes of the pictures they accent. For instance, a sinuous iron bar echoes the curves of an odalisque by Cezanne.

A single day is rarely sufficient to see any museum, and this is truly so with  the Barnes. A person could easily spend an entire day in one room and feel sated. (And one could certainly post an entire blog on any single room…if not on any single painting.)

the Barnes. A person could easily spend an entire day in one room and feel sated. (And one could certainly post an entire blog on any single room…if not on any single painting.)

While so many of the paintings are very familiar and are such a part of Western culture, they were not so when Barnes first bought them. (The $1490.00 that he spent on the eight Picasso’s attests to that!) He had traveled to Europe on his honeymoon and had befriended Leo Stein, who with his sister Gertrude had become such great patrons of Picasso and Matisse. Barnes then commissioned his high-school friend, the artist William Glackens, to Paris to buy art for him. Barnes trusted him completely, and Glackens purchased the first twenty paintings of the collection.

Another story, tells how Barnes himself went into one particular gallery, liked what he saw and bought 52 paintings. Could you imagine a gallery owner today with that sort of sell? Could you imagine the cost? But aside from having money, Barnes also had an extraordinary eye–and an extraordinary vision.

Barnes had made his money by inventing a chemical preparation used to disinfect the eyes of newborns. He spent his money on opening our eyes to the glories of twentieth century art.

Today, despite the wrangling and the bad blood, despite the legal pyrotechnics and the extra-legal manipulations, the Barnes Foundation is nevertheless one of the great centers of modern art–and the controversial relocation is truly a masterpiece.

And more importantly: amid all this hubbub, amid all the controversy, it is a place of extraordinary peace and beauty.

It’s not a bad place to spend a Sunday afternoon.

Brueghel, Auden, and the death of my mother

My mother died yesterday.

She was a simple, quiet, sweet woman whose last few months were horrible. And while it might sound cold-hearted, I can honestly say she is better off today than she was the past few weeks. For better or worse, at least she is now at peace.

And while I have a good number of siblings and a large network of friends and relatives with whom to share the loss, privately I turn to Art with a capital “A.”

The picture above is of a painting by Pieter Brueghel. Entitled Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, it depicts the legendary fall of Icarus, who (in one story) famously disobeyed his inventive father and flew too close to the sun. The sun melted the wax holding together the wings that his father had fashioned, and he crashed into the sea. Through the ages, Icarus has become a two-sided symbol for artists: he is either a symbol of blatant disobedience akin to Eve or Pandora or Deidre or a symbol of great striving, of “flying to the sun,” of grabbing all the gusto one can. I usually lean to this second interpretation and see Icarus as an example of risking it all in pursuit of one’s dreams.

Anyway, this painting is one of my very favorites because

Brueghel has depicted this grand, mythic tragedy as happening amidst the pedestrian goings-on of daily life. If you look closely, you can see Icarus’ legs darting into the water in the right hand corner of the canvas. If you are not looking for them –and did not have the title of the painting to clue you toward Icarus–you might miss them entirely in the busyness of the entire painting. There is a shepherd, a ploughman, a single fisherman, a stately ship and a far-away city, but the boy falling out of the sky barely registers on their existence.

A very famous painting, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus also has been the subject of several poems, most notably by Auden and William Carlos Williams.

Below is W.H.Auden’s poem about the painting which now hangs in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Artes Belgique in Brussels:

Musée des Beaux Arts by W. H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

So yesterday, after the mortician took my mother’s body away, after my brother and sisters and I cleaned out her personal effects and donated her clothes to the needy, I drove away and stopped at a convenience store for a sandwich. The store was extra crowded, there was a particularly annoying man in line, and the cashier herself was particularly surly. I wanted to yell to them, to say, “Hey, don’t you know my mother just died?!” But of course I didn’t and of course they couldn’t have. They were simply going about their normal Saturday routines.

Instead I thought of Brueghel and Auden and Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.

Yet, Auden missed another part of the equation. While it is true that the world goes on despite, and during, moments of personal tragedy, it also does the same in moments of great personal triumph. We tend to think that much of this existence is about us, about our heartbreaks and our victories–and very little of it really is.

Anyway, my world is different today than it was yesterday. I must meet with siblings to arrange funeral services, arrange affairs at work for missed time, try to find a wearable suit for the funeral…and the entire time the great big world will go spinning along, unaware of what any of us are dealing with.

As Auden said, “they were never wrong,/The Old Masters.”

Margaret (Peggy) Bohannon

nee McNeila

1929-2012

Requiescat in pace

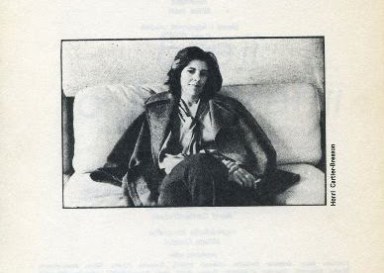

Susan Sontag

I have always been fascinated by Susan Sontag. I envied her seeming crystal-sharp intelligence, her confidence in her opinions, her strength in writing, her omnivorous reading. While I certainly have not read everything of hers, I have read quite a lot. Once as a reader for The Franklin Library’s First Editions, I read the galleys of The Volcano Lover, her historical novel about the triangle between Sir William Hamilton, his wife Emma and Lord Nelson. It was the first piece of fiction of hers I had read. Like all of her writing it was intelligent, sharp and incisive. And it had a truth that can only be found in fiction. Her following novel, In America, was not as satisfying for me–it seemed undone. Or perhaps overdone, might be a better word, for the brilliant characters and storyline are over-examined and over analyzed as if Henry James were writing the screenplays for MadMan. The novel is crushed by the intelligence.

I have always been fascinated by Susan Sontag. I envied her seeming crystal-sharp intelligence, her confidence in her opinions, her strength in writing, her omnivorous reading. While I certainly have not read everything of hers, I have read quite a lot. Once as a reader for The Franklin Library’s First Editions, I read the galleys of The Volcano Lover, her historical novel about the triangle between Sir William Hamilton, his wife Emma and Lord Nelson. It was the first piece of fiction of hers I had read. Like all of her writing it was intelligent, sharp and incisive. And it had a truth that can only be found in fiction. Her following novel, In America, was not as satisfying for me–it seemed undone. Or perhaps overdone, might be a better word, for the brilliant characters and storyline are over-examined and over analyzed as if Henry James were writing the screenplays for MadMan. The novel is crushed by the intelligence.

However, I have read much of her non-fiction: Against Interpretation and Other Essays (1966), On Photography (1977), Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors (1978 and 1988) and Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). (The Illness as Metaphor book was revamped in 1988 in order to address the scourge that was AIDS in the 1980’s.) It is this non-fiction, her essays that make her an major figure of the late 20th-century. It is in these essays that the true brilliance shines. Hers is a hard intelligence, but a very clear intelligence. Her Against Interpretation gave readers an argument “against what something means” and for “what something is.” It includes insightful–and new–readings of Sartre, of Beckett, of Bresson, among others. Illness as Metaphor moves us from the tuberculosis and consumption that affected so many of the 19th century’s literary characters and creators to the cancer that became the overriding metaphor of the twentieth. On Photography discusses the relatively new art of photography–only since the mid-19th century– in a way that will change how even the most amateur viewer–myself– views photographs again. And at the beginning of the second Iraq war, I once gave a section of Regarding the Pain of Others to a class of 18-year olds, and it surprised me how well it worked with theml.

A few years ago, I went to the Brooklyn Art Museum to see a photographic exhibit on Sontag by Annie Liebovitz, perhaps America’s most famous and celebrated portraitist at the time. Liebovitz–who had had a decades long romantic relationship with Sontag–captured Sontag’s final years, among family and friends. Many of them were during her final days, during her final battle with cancer. To this day I don’t know if I am more affected by the words Sontag wrote or the images of her that I saw that day. Both, suggest an admirable toughness and wit.

What I also don’t know is why today, the NYTimes decided to publish a sampler of Sontag’s work in the Week in Review section of the Sunday paper. There is no anniversary that I know of. It just appeared. But good, it made for a good read on a Sunday morning, and a good afternoon going through some old books. The excerpts are just that–excerpts–but they show the range, the depth and the honesty of her writing and her mind. The article is below: enjoy it.

Opinion

A Sontag Sampler

By SUSAN SONTAG

Published: March 31, 2012

Art Is Boring

Schopenhauer ranks boredom with “pain” as one of the twin evils of life. (Pain for have-nots, boredom for haves — it’s a question of affluence.)

People say “it’s boring” — as if that were a final standard of appeal, and no work of art had the right to bore us. But most of the interesting art of our time is boring.

Jasper Johns is boring. Beckett is boring, Robbe-Grillet is boring. Etc. Etc.

Maybe art has to be boring, now. (This doesn’t mean that boring art is necessarily good — obviously.) We should not expect art to entertain or divert anymore. At least, not high art. Boredom is a function of attention. We are learning new modes of attention — say, favoring the ear more than the eye — but so long as we work within the old attention-frame we find X boring … e.g. listening for sense rather than sound (being too message-oriented).

If we become bored, we should ask if we are operating in the right frame of attention. Or — maybe we are operating in one right frame, where we should be operating in two simultaneously, thus halving the load on each (as sense and sound).

•

On Intelligence

I don’t care about someone being intelligent; any situation between people, when they are really human with each other, produces “intelligence.”

•

Why I Write

There is no one right way to experience what I’ve written.

I write — and talk — in order to find out what I think.

But that doesn’t mean “I” “really” “think” that. It only means that is my-thought-when-writing (or when- talking). If I’d written another day, or in another conversation, “I” might have “thought” differently.

This is what I meant when I said Thursday evening to that offensive twerp who came up after that panel at MoMA to complain about my attack on [the American playwright Edward] Albee: “I don’t claim my opinions are right,” or “just because I have opinions doesn’t mean I’m right.”

•

Love and Disease

Being in love (l’amour fou) a pathological variant of loving. Being in love = addiction, obsession, exclusion of others, insatiable demand for presence, paralysis of other interests and activities. A disease of love, a fever (therefore exalting). One “falls” in love. But this is one disease which, if one must have it, is better to have often rather than infrequently. It’s less mad to fall in love often (less inaccurate for there are many wonderful people in the world) than only two or three times in one’s life. Or maybe it’s better always to be in love with several people at any given time.

•

On Licorice, Bach, Jews and Penknives

Things I like: fires, Venice, tequila, sunsets, babies, silent films, heights, coarse salt, top hats, large long- haired dogs, ship models, cinnamon, goose down quilts, pocket watches, the smell of newly mown grass, linen, Bach, Louis XIII furniture, sushi, microscopes, large rooms, boots, drinking water, maple sugar candy.

Things I dislike: sleeping in an apartment alone, cold weather, couples, football games, swimming, anchovies, mustaches, cats, umbrellas, being photographed, the taste of licorice, washing my hair (or having it washed), wearing a wristwatch, giving a lecture, cigars, writing letters, taking showers, Robert Frost, German food.

Things I like: ivory, sweaters, architectural drawings, urinating, pizza (the Roman bread), staying in hotels, paper clips, the color blue, leather belts, making lists, wagon-lits, paying bills, caves, watching ice-skating, asking questions, taking taxis, Benin art, green apples, office furniture, Jews, eucalyptus trees, penknives, aphorisms, hands.

Things I dislike: television, baked beans, hirsute men, paperback books, standing, card games, dirty or disorderly apartments, flat pillows, being in the sun, Ezra Pound, freckles, violence in movies, having drops put in my eyes, meatloaf, painted nails, suicide, licking envelopes, ketchup, traversins [“bolsters”], nose drops, Coca-Cola, alcoholics, taking photographs.

This material is excerpted and adapted from the forthcoming book “As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks, 1964-1980,” by Susan Sontag, edited by David Rieff. A version of this was originally published in the NEW YORK TIMES, April 1, 2012.

Deluded Knights in Philadelphia

About two and a half blocks from where I live there is a small patch of grass at the triangle where three streets cross–Girard Avenue, American Avenue and 2nd Street. There, Girard is a busy, double-wide street with an active trolley line, restaurants, tattoo parlors, bodegas, beauty salons and banks. 2nd Street is a bit smaller but filled with restaurants, bars, boutiques, and galleries and American is but a desolate patch with a beer distributor and the abandoned stables where the horses and carriages that circle the historic area used to be housed. On the north side of Girard, American is just beginning to blossom, anchored by the beautiful Crane Building which houses both the Indigo Art Galleries and the Pig Iron Theater Company.

Sitting in the triangular patch made by these three streets is a large statue of Don Quioxote astride his horse Rocinante. Why Don Quioxte? I am not sure. The plaque on the statue says that it was a gift from a “sister city” in Spain, Ciudad Real, and it is an exact replica of an original sculpture by Joaquin Garcia Donaire. But again, why Quixote?

Quioxte was in many ways a mad man…an idealistic, well-meaning mad man, but mad nevertheless. His quests and adventures, while couched in the greatest of intentions and wrapped in the mantle of chivalry and honor, were actually farcical and embarrassing. Quioxte’s famous battle against the windmill, which he had perceived as a dragon, has given us the idiom “Tilting at Windmills,” a phrase for fighting against the wrong thing, about declaring war on something that is un-winnable and un-fightable, or for dreaming a victory against something that is not at all what one was fighting for or against. So why is he in Philadelphia?

Quioxte was in many ways a mad man…an idealistic, well-meaning mad man, but mad nevertheless. His quests and adventures, while couched in the greatest of intentions and wrapped in the mantle of chivalry and honor, were actually farcical and embarrassing. Quioxte’s famous battle against the windmill, which he had perceived as a dragon, has given us the idiom “Tilting at Windmills,” a phrase for fighting against the wrong thing, about declaring war on something that is un-winnable and un-fightable, or for dreaming a victory against something that is not at all what one was fighting for or against. So why is he in Philadelphia?

Philadelphia prides itself on its place in the history of the United States. It was from here that the colonists argued, debated and hammered out a Declaration of Independence and then a Constitution, both of which are revered around the world. Throughout the year, one would be amazed at the hordes of international tourists who pose for pictures in front of the revolutionary landmarks, in front of Independence Hall or the Liberty Bell. In a world where independence and liberty are not a given, it is humbling to see so many people come to honor it here in Philadelphia. And so, why Don Quioxte that deluded knight? Is the fight for civil liberties and religious tolerance–two concepts that were the lynchpins of the city–a quioxtic dream? Is working towards harmony and liberty really just a pipe-dream of some writers from the 18th-century Enlightenment.

But this thing with knights gets odder still. Just twenty-three blocks due west of Don Quioxte is a blazingly gilded statue of Joan of Arc. Now, I have always loved the story of Joan of Arc. (I may be one of the few people who have read Mark Twain’s novelization of her life other than for academic credit. And I have read several serious biographies of her as well.) I have always loved her spunk, her feistiness, her belief in her cause. But one has to admit, as a representative of knighthood, she is a bit suspect. This was a woman who heard voices, voices that encouraged her to leave her simple peasant life, shift to a more masculine nature, don armor and lead a country into battle. Which she then went and did! This statue–which is a copy of the one that sits in the Place des Pyramides in Paris and was sculpted by Emmanuel Fremiet–looks across at the neo-classical beauty of the Philadelphia Art Museum and is the starting point for the famous Kelly Drive. It is blindingly gilt and quite handsome.

But then again why, in this city that put an end to medieval monarchies and aspired to a new form of human government, has a heroine of the monarchistic tradition been placed in such a prominent public position?

It probably means nothing, but I think of them often. They are basically on the same street, less than 2.5 miles apart in a straight line. They are undoubtedly–along with Shakespeare’s Falstaff –the most suspect knights in all of history. And yet they are here, in the city that shook off a king and aspired to freedoms never before imagined.

(A kind of interesting irony: just as Joan of Arc died in the flames in 1431, the model for the Joan of Arc statue, 15-year-old Valerie Laneau, burned to death in a house fire when she was 77.)