“There are three things all wise men fear: the sea in storm, a night with no moon, and the anger of a gentle man.” – Patrick Rothfuss, The Wise Man’s Fear

Art

Quote #41: “…someday, everything’s gonna be different.”

L.A. … the rain … and the raving Jesus

In late February I had the chance to be in Los Angeles for a long weekend. It promised to be a sweet respite from the Northeastern winter we had all been going through, a winter that alternated sub-arctic temperatures with crippling snow storms. And when I left the weather reporters were gearing up their apocalyptic terms for yet another storm which was to arrive.

Anyway, Southern California seemed a treat in February.

In 2013, Los Angeles received about 3 inches of rain for the entire year. The Friday I was there, it received a little more than 6—with much more in the San Berandino valley.

But what the rain does do is it forces one inside and we spent an enormous amount of time in the wonderful LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

When we arrived we walked into a free exhibit of Diane von Furstenberg’s design. I know little of fashion, but I did recognize the name. The entrance of the exhibit was papered with oversize advertisements, movies, and photos of people wearing von Furstenberg’s dresses–particularly her iconic wrap-around dress.

The next room presented a phalanx of white mannequins clothed in Von Furstenberg’s dresses. In many ways, it resembled a scene from a bad science-fiction film:

The floors and walls were painted in continuous patterns, so that it appeared that one entered the pattern itself. It was all very op-art-ish. (In fact, Von Fustenberg, the LACMA and the Andy Warhol museum had collaborated to create special edition t-shirts–which were way out of my t-shirt budget category!)

We moved from one gallery to another–running through pouring rain from one building to the next. We entered the Linda and Stewart Resnick pavilion (for whom I once worked) where a small Hockney exhibit was being mounted. We visited the Mexican gallery with its Riveras and Kahlos. We visited an exciting exhibit on soccer–gearing up for the 2014 World Cup. And we delighted in the funky moving sculptures: Chris Burden’s “Metropolis II, a city of 1,100 Hot-Wheels, and Jesus Rafael Soto’s remarkable “Penetrable,” kinetic sculpture of yellow plastic ribbons that hangs from ceiling to floor in the hundreds and which one can walk through.

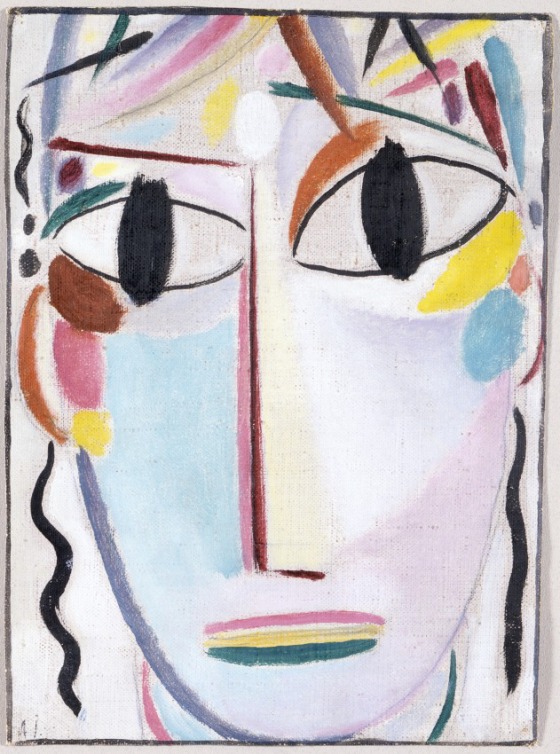

But it was in the modern art gallery, in the early 20th-century Eastern European room, that I discovered a delightful artist and painting that I had never known before. It was Alexei von Jawlenski’s “Young Christ.” Working boldly apart from the long tradition of Christ portraits, this work was brightly colored and freely drawn, and it popped with excitement.

My daughter said it looked as if Christ had been to a “rave,” so that is what we christened it: The Raving Jesus.

Quote #31: Salvador Dali on madness

Movie Review: The Artist and the Model dir. by Fernando Trueba…simply a masterpiece

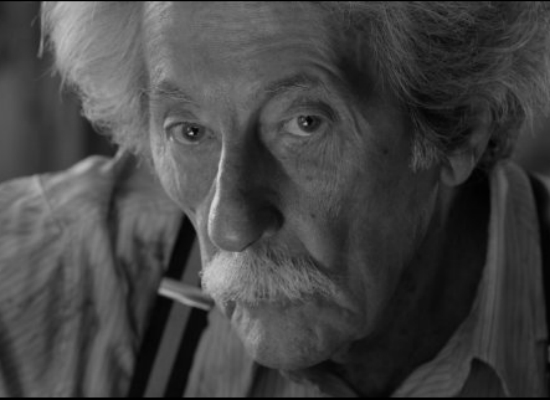

Trueba’s The Artist and the Model is the art of film raised to the highest level. Its story is poignant, its intelligence is palpable, its cinematography is mesmerizing, its acting is subtle and powerful and its beauty is breathtaking. And in a film that addresses life and art and beauty and work, it is the very face of the artist Marc Cros (Jean Rochefort) that comes to represent them all, a face that Trueba closes in on with love and craftsmanship, a face that seems to contain the very themes of the film itself.

An elderly sculptor (Rochefort) has isolated himself in a small village apart from the business of war in Occupied France during World War II. One day, his wife (Claudia Cardinale) discovers a Spanish refugee (Aida Folch) sleeping rough and washing herself in the village’s fountain, She brings the girl home to her husband to be his next (and last) model, to be the muse for him that she had once first been.

In exchange, the young woman, Mercè, receives room and board and a salary. Awkward at first, their relationship–the artist and the model– grows into a symbiotic one: she inspires the sculptor and he transforms her into his masterpiece. In their life together, she is joyous and he is crotchety. She is young and he is wise. She is involved in the war and he is trying to keep it at bay.

The film is shot in black and white. But to merely say “black and white” does not capture the luminous beauty of the photography. Each scene has a shimmering silver light that imbues the film with both beauty and gravitas. Each scene seems as if a Richard Avedon portrait had come to life. I do not exaggerate when I say that this may be the most beautiful film I have ever seen.

The slow rhythm of the film may be off-putting to some, but it should not. We are watching something very special here. The creative process has always been a difficult one to portray, and a slew of films have done it badly. But not this. This comes as close as is probably possible in capturing the artistic process: idea, incubation, trial, and execution.

And aside from our watching the process, there is the sculptor’s instruction for his model. At one point, he tells her his version of creation. God, he says, having created the beauty of the universe, wanted someone to share it with and so he created woman. (He believes the female body and olive oil are God’s greatest creations.) Together, God and the woman, had a son Adam.

At another time, he takes a scribbled pen-and-ink drawing of Rembrandt’s and explains to Mercè what the artist was doing. In a simple three minutes of film, he gives a master class in art–and one that any art student should attend to.

We learn more about the artist when a Nazi officer drives up to his mountain studio. Mercè–who at that point is hiding a wounded Resistance fighter–is naturally on alert. But the Nazi is there to discuss the biography he is writing on the artist. (He already has some 400 pages.) After the two discuss the book, the Nazi departs, telling Cros that he has been transferred to the Russian Front. We get the idea that he’ll never live long enough to finish his book.

The stories surrounding the making of The Artist and the Model are a lesson in creativity as well. Based loosely on the sculptor Aridste Maillol and his final model, Trueba began working on the script in 1990, intending to collaborate with his brother the sculptor Maximo. But Maximo’s young and sudden death, put Trueba off the project. It was not until, Rochefort, whom Trueba had already considered to play his sculptor, told him he was retiring that Trueba decided to go ahead with it.

It is undoubtedly, the high point of Trueba’s career so far, as it probably is also for Jean Rochefort. Indeed, like the sculptor that he plays, Rochefort’s finest performance–in a long and celebrated career–is here in this his final performance.

Certainly, there is much good art around. There is very little great art. The Artist and the Model falls into the second category.

Here is the trailer:

Weekly Quote # 20: September 1, 2013

Renoir…Cotton Candy…and Barbie’s Bordello

We probably all can imagine that little boy or girl at a fair, a carnival, or an amusement park, who seeing an enormous pompadour of pink or blue cotton candy (spun sugar to some of you) insists on getting the largest size. We can see further the sticky stains upon their faces, the crazed shock of sugar in their eyes. And we can empathize with them and their queasy stomachs that a night filled with cotton candy is certain to produce.

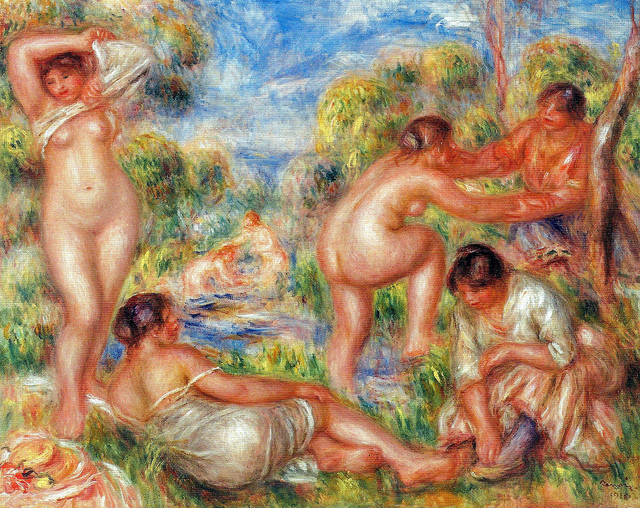

That’s how I feel about Renoir and his nudes.

I spent more than three hours at the Barnes Foundation last Friday night. And as always, it is a mind-boggling collection of early modern art, African sculpture, and American furniture, decorative and industrial arts. I could spend a lifetime looking at the Modglianis and Mattisses. I am fascinated by Chaim Soutaine and George Seurat. And Henri Rousseau I find thoroughly relaxing and amusing.

But it is the Renoirs that I find cloying.

Barnes owns 181 Renoirs that encompass the span of the artist’s career. Now, there is much that I like about Renoir: his early works, the group portraits and the early nudes. But the more famous nudes, those cotton candy swirls of creams, oranges, pinks and yellows, I find difficult to look at.

By contrast, one of my favorite paintings in the collection is also a nude: Amadeo Modgliani’s Reclining Nude from Back. Is it lifelike? No. But it is sensuous and intriguing and narrative and appealing and pleasing. And what more could a person want from a work of art?

Modgliani’s attenuated figures with their mask-like visages, I find fascinating. I find a story in each of their stony faces. Likewise, I delight in the classical innocence of Picasso’s Girl with a Goat or the bold outlines and patterns of Mattisse’s Reclining Nude with Blue Eyes. Each is so distinct in itself, so original in its view of the human body.

Renoir’s nudes, on the other hand, I find distracting in their busyness. I find them tiring and I tend to pass over them quickly.

To me, they look like how Barbie would decorate a bordello if she ever became a Madam.

Book Review: Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas by Rebecca Solnit

Rebecca Solnit begins her book with this quotation from Thoreau:

“I have traveled widely in Concord.”

Concord really isn’t that big a place to “travel widely” in, but that is the argument of Solnit’s Infinite City: every place contains an infinite number of “maps” with which we travel, and within her book Solnit creates a unique, intriguing, and entertaining series of maps of her city, San Francisco.

Now, you know you are in heady territory when in the first three paragraphs Solnit makes multiple references to Borges and Calvino, both fantastic cartographers and creators of worlds that have never existed. Yet, Solnit is every bit as imaginative and perceptive. She reveals a given place (San Francisco) in ways that had never been categorized before and introduces new perspectives on the city that have never before been imagined.

In her introduction, Solnit explains her method thus:

Every place is if not infinite then practically inexhaustible, and no quantity of maps will allow the distance to be completely traversed. Any single map can depict only an arbitrary selection of the facts on its two-dimensional surface… . For Infinite City, this selection has been a pleasure, an invitation to map death and beauty, butterflies and queer histories, together, with the intention not of comprehensively describing the city but rather of suggesting through these pairings the countless further ways it could be described. (I also chose pairs in order to use the space more effectively to play up this arbitrariness, and because this city is, as all good cities are, a compilation of coexisting differences, of the Baptist church next to the Dim Sum dispensary, the homeless outside the Opera House.)

And this is how the book works. The “arbitrary selection of facts” are surprising and unconventional. There are maps of industries and bee migrations and “tribal neighborhoods” and gang-lands and right-wing bastions and bygone areas of entertainment and carousal. And the pairings are both startling and sensible. For instance, the map entitled “Poison/Palate: The Bay Area in your Body” is accompanied by Solnit’s essay “What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Gourmet.” In both, the reader is given a map of the major dumpers of toxins into the environment (often food and wine growers) and the sites of delicious, food providers. (Often the two overlap.) The key to the map gives symbols for EPA SUPERFUNDS, Poison Sites, Palate Sites, Poison/Palate Sites and Wineries.

The population map–the current population not the map of those who have left and those who are arriving–is set up as a “tribal” map. The expected ethnicities are cited–the Chinese, the Irish, the Korean, the Mexican–but they are accompanied by neighborhoods where the “tribes” include skateboarders, people with ties, transgender people, etc. Again, this is accompanied by a moving essay by Solnit about the ever changing population shifts of her city.

But it is the pairings that are the most intriguing. One map, entitled Death and Beauty, tracks the murders in the city during the year 2008 and the locations of Monterey cyprus trees throughout the city; another entitled Dharma Wheels and Fish Ladders lists salmon streams, hatcheries and viewing sites along with the location of Zen monasteries, schools, and core sites; and still another, entitled Monarchs and Queens, reveals the locations of various butterfly locations and queer public spaces.

Each of the twenty-two maps are jewels of color, design, and information. They are beautiful, as are all of the illustrations throughout.

While Solnit did not write all of the essays that accompany the maps, she did write the majority and her fellow essayists are similar in spirit, similar in the way they look at their ever-changing city. In a recent piece for the London Review of Books entitled “Google Invades” (February 2013), Solnit bemoaned the changes that have occurred in her city with the influx of Silicon Valley money. She felt that the variety in the city’s fabric–in its economics, its life styles, its ethnicities, its politics, and its arts– was being leveled and watered-down with the influx of cyber-millionaires. The city–not just a neighborhood– was being gentrified.

Solnit sees her city, San Francisco, in many, various ways, in multiple perspectives that have accrued layer after layer through the years that she has lived there. These views are both nostalgic and forward-looking, while still very much ensconced in the present, no matter how ethereal that might be. And while some of these layers may now have physically vanished, they remain in her memory, in her view of the city.

And they remain in this amazing, attractive, and addictive book.

Roasted Picasso, Braised Mattise, Charred Freud: Art in the Oven

Stolen Picasso and Monet art ‘burned’ in Romanian oven

Romanian investigators have found the remains of paint, canvas and nails in the oven of a woman whose son is charged with stealing masterpieces from a Dutch gallery in October last year.

(click headline to read original article)

The burnt remains–pigments, bits of wood, nails–were found in the home of a Romanian woman whose son had been arrested in connection with the heist.The woman, Olga Dogaru, told authorities that she had burned the paintings to destroy any evidence that linked her son to the theft. The paintings, which are valued between $130 and $250 million, have not yet been officially identified with the remains in Mrs. Dogaru’s oven, but the likelihood is great.

And so I began thinking and wondering.

In a small house in Romania, we have fragments of painting primer, paint, wood, canvass and nails. In a way, these famous paintings have been “deconstructed” to their most basic elements. What element is missing? Genius? Kind of nebulous. Inspiration? Maybe even more so. Certainly execution and vision.

But what was once one thing is now something else. (In many ways, isn’t that a way of defining art itself.)

One of the officials working on the case stated that if these oven remains are indeed the paintings they are looking for then Olga Dogaru’s actions are a “crime against humanity.”

Come on, now. After the horrors of the Holocaust, the crimes of Pol Pot, various tribal genocides, corporate environmental rape, the atrocities of the twentieth century and the new horrors of the young twenty-first, I think calling this a “crime against humanity” is a bit overstated and a bit overdramatic.

Don’t get me wrong. I am no philistine. I love art. It is a very important and crucial part of my life, day in and day out. I love amateurish, clunky student art and exquisite paintings by the Old Masters. I love rough draft architectural models and elegant Brancusi Birds in Space. I love the avant garde and the mainstream.

And yet, my life is not appreciably diminished by the loss of these individual paintings. There are paintings that I love, that I am lucky to be able to visit often. But if they were gone, life would go on. For me, as well as most of the other 7 billion people on earth.

Undoubtedly, it is a shame that these paintings are gone forever. (A bit amusing that they were destroyed by a mother trying to protect her ne’er-do-well son and probably unaware of the magnitude of her actions.) The monetary loss is arbitrary…and irrelevant. And the fact they they will never be seen in the original is regrettable.

But the entire story has me thinking hard about Art. What is it? What is it for? What is its relationship with society? What are the tiers? And what and who determines them?

To be honest, I don’t know the answers. But they are important questions to ask.