I used to think that it was only Americans who were so caught up with the experience of “High School.” I had believed it was an American construct, an over-idealized rite of passage that had spawned too many bad television series and “coming of age” films. I had believed it was strictly an American thing.

I used to think that it was only Americans who were so caught up with the experience of “High School.” I had believed it was an American construct, an over-idealized rite of passage that had spawned too many bad television series and “coming of age” films. I had believed it was strictly an American thing.

I’ve known many men for whom those “high school” years were the very pinnacle of their lives. It is those days that they keep referring to, those days by which they measure all others. I mean I know men in their 40s and 50s, in their 60s and 70s, even in their 80s whose conversation invariably turn to the high-jinks and glories of their high-school days.

But I was wrong.

Haruki Murakami’s novel Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage revolves around five Japanese high school friends and the long-lasting effects of the decisions they made when they were twenty years old. They are now in their mid-thirties; two are living in their hometown, one has moved to far-away Finland, one to cosmopolitan Tokyo, and the fifth one is dead, murdered. The one-time connectedness of these five high-school friends haunts the hero, Tsukuru Tazaki.

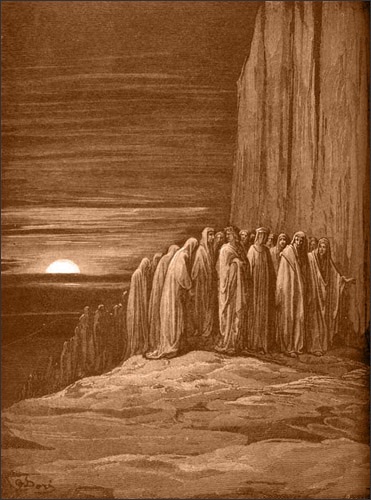

Tsukuru–whose name is the only one the five which does not have a color attached and who believes himself to be “colorless–was abruptly dropped from the group when he was a sophomore in college in Tokyo. And he never was given an explanation, just the order to never contact them again. The separation caused Tsukuri months of suicidal depression and then years of self-doubt, wonder, and the inability to relate to people. For Tsukuru, the five high school friends were an unprecedented harmony of spirits. And yet there were several cracks in this group which he was too nice to notice.

Tsukuru’s name in Japanese means “one who makes things,” and indeed, that’s what he does. He makes railroad stations. And in Japan, railroad stations are a very big deal and making connections is an intrinsic part of Tokyo life. Yet his treatment by his high-school friends has left him unable to make connections with people. There have been several romantic liaisons, but nothing serious and nothing he wished to pursue further. There was a friendship–tinged with a touch of homo-eroticism–that ended as abruptly as his friendship with his high-school mates. He was simply abandoned one day, his friend moving away from Tokyo with no forewarning and no intention of staying in touch.

And so we follow “colorless” Tsukuru as he tries to make his way in the world.

I needed a novel like Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki. There had been too few novels lately that gripped me from the beginning and made me read obsessively until I was finished. And Murakami has done that for me before. While I can’t remember the exact plots of his Kafka on the Shore or NorwegianWood, I do remember the obsessiveness with which I read them. I can remember jotting down notes, following up allusions, taking notes. I remember protagonists who were like Tsukuru Tazaki: thoughtful, introspective, aware young men, burdened by what they cannot change in the past and fearful of the uncertainties of the future. And I remember getting caught up in their sadness and their serious attempts to make sense of their world. Murakami’s novels are both thoughtful and fascinating, outwardly exotic and inwardly philosophic.

And also I remember the fascinating side-trips of information. In Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki, there is an odd but brief discussion of the genetic dominance of a sixth finger; there is a continual look at the music of Listz, particularly the “Le Mal du Pays” section of his suite “The Years of Pilgrimage.” It is a piece that the young murdered friend played often when they all were together, and it is a record that his friend Haida had coincidentally left at Tsukuru’s apartment before he had left him. Towards the end of the novel, Tsukuru visits one of his old high-school friends–still seeking enlightenment as to why he was so unceremoniously dropped–and the friend has the piece in her pile of CDs. The two reach some reconcilliation listening to Listz.

And then finally there is the subject of trains and of Tokyo’s public transportation. When Tsukuru needs time alone, when he is filled with angst and confusion, he goes to the train platforms and watches the trains and the people. There is a certain peace he finds in the uniformity and the precision which such a place exhibits, against what seems impossible odds. (Shinjuko Station handles 3.5 million passengers a day!)

I had skipped Marukami’s novel before this, 1Q84, for a variety of reasons. It was a mistake on my part and one I will rectify shortly.

You can listen to the very recording of Listz that Tsukura played on his stereo in his apartment here: